In this post, Stone Center Senior Scholar Paul Krugman discusses how tariffs might affect international capital flows and the U.S. economy.

By Paul Krugman

Well, we’ve had our election, and everything is about to change. It’s an understatement to say that I’m not happy about the results. But one (very small) consolation comes from an observation by my old teacher Evsey Domar: bad times can lead to interesting economic analysis.

So as we watch the international economic order (and much else) come apart, I’m going to spend some time returning to my roots and trying to figure out how trade wars and other shocks may play out. For now the Times isn’t allowing me to do a proper newsletter/blog (but watch this space), so initially I’ll be posting items here, on the Stone Center site, linking to them via social media.

First up: Trump has long been obsessed with tariffs, in large part because he believes that America’s trade deficit means that we’re a victim. Never mind all the reasons that’s a bad diagnosis: can/will Trump’s policies actually reduce the trade deficit?

Conventional wisdom among economists says no, for very good reasons. But some aspects of that conventional wisdom have been nagging at me. In what follows I’ll argue that Trumpism may indeed reduce the U.S. trade deficit, but not for reasons Trump will like. Mainly, the U.S. trade deficit is the counterpart of large capital inflows into the United States, and barriers to trade in goods also end up impeding the mobility of capital. So Trump’s policies may crater international capital flows, sharply reducing foreign investment in the United States, and the counterpart of that reduced inflow will be a smaller trade deficit.

I’ll get to that argument in due course. But first some of the conventional arguments about why tariffs won’t reduce the trade deficit.

Tariffs and trade balances: Conventional wisdom, partial equilibrium

Many discussions both of Trump’s past tariffs and of his plans for the future argue that they’ll be counterproductive using partial equilibrium analysis. If any non-economists are reading this, what I mean is that they focus only on direct effects and don’t take into account indirect macroeconomic effects of tariffs, especially their impact on the value of the dollar.

Even so, there are two big reasons to be skeptical that tariffs, even at the high rates Trump is talking about, would do much to reduce trade deficits.

First, the modern U.S. economy is deeply embedded in global value chains; manufacturing, in particular, relies heavily on imported inputs. The most conspicuous example is production of cars. There really isn’t, at this point, a U.S. auto industry; there’s a North American auto industry, in which the production process involves complex webs of suppliers spread across the United States, Mexico, and Canada. High tariffs across the board would sharply raise production costs, so that it’s quite plausible that manufacturing output and employment would actually fall.

Second, U.S. tariffs will be met with substantial retaliation and/or emulation. My guess is that the Trump people have an exaggerated sense of U.S. economic power — similar, in a way, to the exaggerated sense of U.S. military power that was so widespread before we invaded Iraq.

The truth is that there are three trading superpowers in the world today: America, China, and the European Union. The U.S. is somewhat bigger than the others in terms of dollar GDP, although our economy is smaller than China’s once you adjust for purchasing power. But nobody is dominant.

And while Europe is frustratingly unable to act collectively on many issues, the EU is a customs union in which common external tariffs are set in Brussels. So Europe will react as a unit to Trump’s tariffs — and the reaction is likely to be strong. As for China, it matched the U.S. more or less tit for tat during the first Trump trade war, and there’s every reason to believe that this will happen again.

The one thing you might say is that because America imports more than it exports, foreign tariffs on U.S. exports might not fully offset the effects of U.S. tariffs on our imports. This will, however, be cold comfort to, say, U.S. farmers, who do depend greatly on exports. And then there are those macroeconomic, general equilibrium effects.

Conventional wisdom: General equilibrium

I think it’s safe to say that most economists don’t believe that Trump’s tariffs would reduce the trade deficit even if it weren’t for retaliation and the effects on supply chains. Our skepticism comes down to a basic accounting identity:

Trade balance + Net investment income + Net capital inflows = 0

The sum of the first two terms is the current account balance, which you can think of as the trade balance broadly defined. And you can’t reduce the current account deficit unless capital inflows fall — like gravity, it’s the law. Try to squeeze the trade deficit by imposing tariffs that reduce imports, and it will be like pushing on a balloon: the deficit will just expand somewhere else.

How does this work in practice? Usually through the exchange rate. Impose tariffs on U.S. imports, and even if you assume that there isn’t effective foreign retaliation, the dollar will just rise, making U.S. exports less competitive.

This isn’t just theory. A few years ago Furceri, Hannan, Ostry and Rose (2019) did a massive study of the effects of tariffs in many countries, whose results they summarized thusly (emphasis mine below):

We find that tariff increases lead, in the medium term, to economically and statistically significant declines in domestic output and productivity. Tariff increases also result in more unemployment, higher inequality, and real exchange rate appreciation, but only small effects on the trade balance.

Despite this evidence, however, the proposition that Trump can’t reduce the trade deficit has, as I said, been nagging at me. Why? Because I don’t think we can take net capital inflows as given.

Tariffs and capital flows

What drives international capital flows? The textbook story is that capital flows to equalize rates of return across countries. And I do mean textbook. Figure 1 is taken from the Krugman/Wells principles textbook:

Figure 1: Textbook capital flows, from Krugman and Wells

In case you’re wondering about the countries named, we deliberately used 19th century capital flows as a motivating example rather than wade directly into modern disputes.

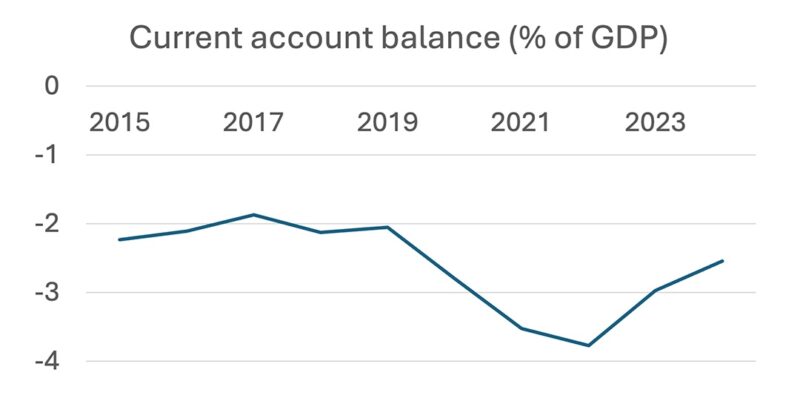

Now, the United States has run sustained current account deficits, the counterpart of sustained capital inflows:

Figure 2: Money incoming, from IMF

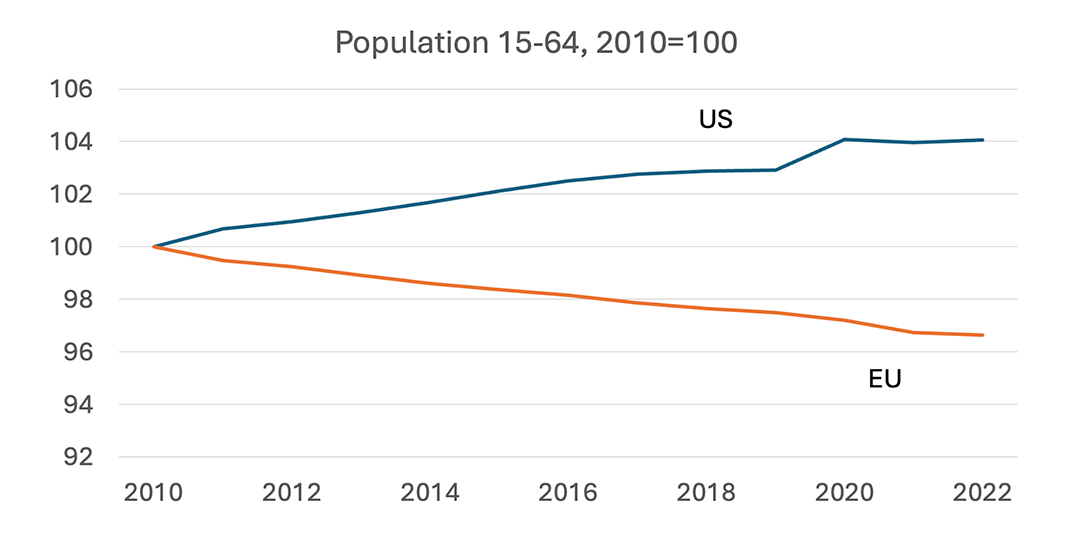

What draws that money in? If I had to give a single reason, it would be demography. Every advanced country has an aging population, with growth in the working-age population slow or even negative; but between somewhat higher fertility and immigration, the demographic slowdown has been less in the U.S. than elsewhere:

Figure 3: The U.S. demographic advantage, from OECD

Obviously this advantage will abruptly go into reverse if Trump actually carries out mass deportations; financial markets are currently betting on higher interest rates because of exploding deficits, but a shrinking labor force would cut the other way. Even Potemkin deportations, which some of my business contacts expect — a few showy roundups that don’t shut down areas like agriculture and meatpacking, which are highly dependent on undocumented immigrants — would deter future immigration. I guess we’ll see.

But my main new argument here is that a tariff-ridden world would also be a world with greatly reduced capital flows; since the U.S. trade deficit is the counterpart of large capital inflows, a global reduction in capital mobility would also squeeze our trade deficit, although it would largely do so by reducing overall investment in the U.S. economy.

The idea that barriers to trade in goods also inhibit capital movements isn’t new, although there hasn’t been a lot of research. The best writeup I’m aware of is a 2001 paper by Obstfeld and Rogoff, which uses that argument to attempt to explain a number of puzzles in international macroeconomics.

It’s a great paper, but to be honest, their formal model isn’t the most elegant thing ever. That isn’t a criticism: I’ve been trying to come up with a slicker version and haven’t succeeded so far.

But maybe I can help a bit with the intuition, starting with a reductio ad absurdum.

Imagine that there were a thriving economy with well-developed capital markets on Mars. Alas, there wouldn’t be much scope for productive trade with that economy: the costs of transporting goods back and forth would be prohibitive. But sending strings of ones and zeroes — which is basically what money is in the modern economy — wouldn’t be all that hard. So couldn’t capital flow from Earth to Mars, or vice versa?

No. Net capital flows are the counterpart of imbalances in physical trade. We can only meaningfully transfer capital to Mars if it lets the Martians buy something real from us, which they can’t. And if Earth investors somehow managed to take ownership of Martian assets, they would eventually want to convert those assets into real goods they can consume back on Earth, which they couldn’t. No trade in goods means no trade in capital.

A more, um, down to earth and less extreme story — basically the one Obstfeld and Rogoff told — goes like this:

Suppose that country A, for whatever reason, offers a higher real rate of return on investments than country B. We would then expect capital to flow from B to A. However, this capital flow must have a rise in A’s trade deficit as a counterpart. And because the doctrine of immaculate transfer is false, the inward capital flow must affect the trade balance via a real appreciation of A’s currency.

Eventually, however, the capital inflows will trail off and investors will begin repatriating their returns. When this happens, A’s real exchange rate will depreciate, cutting into the real return for B’s investors in terms of their own consumption. Anticipating this, capital inflows will fall short of the amount required to equalize real rates of return. If you like, the picture in Figure 1 is oversimplified.

Where do tariffs enter the story? The amount by which the exchange rate must appreciate to accommodate a given inflow of capital depends on how many goods are tradable. If only a small part of production can be exported and a small part of consumption imported, you’d need a very, very strong dollar to produce the kind of trade deficits America currently has. And because what goes up must eventually come down, a U.S. economy with limited trade would be unable to attract foreign investment at current rates.

Again, in my Martian example, where nothing is tradable, no level of the exchange rate can accommodate capital flows. We’re not going all the way there, but a tariff-ridden world with much less trade than we currently have would also be a world with much smaller capital flows. And because the U.S. trade deficit is the counterpart of large capital flows, a global trade war probably would reduce that deficit — not by helping U.S. firms compete with foreigners, but by largely shutting down international movements of capital.

It still seems likely that Trump will be sorely disappointed in his efforts to reduce the trade deficit. But to the extent that he succeeds, it will be for bad, economically destructive reasons: damaging the world trading system will also greatly damage international capital markets.

Read More: