May 7, 2020

In his personal blog post, Branko Milanovic examines data from Pride and Prejudice and Anna Karenina as vignettes to explore income inequality in 19th century literature.

Excerpt:

I hit upon the idea to include the data from “Pride and Prejudice” in a vignette. This was helped by the fact that a few years earlier I wrote with Peter Lindert and Jeffrey Williamson a paper that used English social tables, including Patrick Colquhoun social table from 1801-3. The table almost exactly coincided with the years when the plot in “Pride and Prejudice” is supposed to happen. I was thus able to very nicely locate Darcy, Elizabeth (in her unmarried status) and Elizabeth if she decides not to marry Darcy but to depend on the inheritance of less than 50 pounds per year—a prospect menacingly dangled by the tactless Reverend Collins as he proposes to her—in the English income distribution at the time.

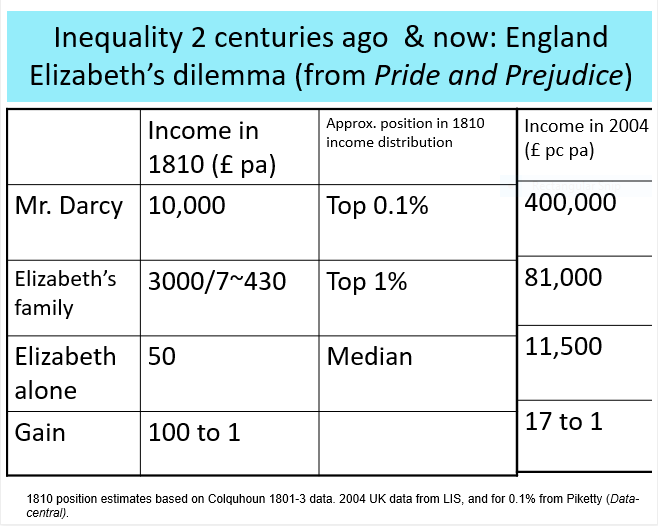

As the table below shows, the range of options for Elizabeth goes from being in the top 0.1% of England’s income distribution to being at the median. The income gap between these two options is 100 to 1. (When she marries Darcy, their household per capita income becomes 5,000 pounds; hence: 5,000/50=100.) As I wrote, “the incentive to fall in love with Mr. Darcy seems irresistible”. The last column shows how much has the gap shrunk today compared to what it was two hundred years ago: being at the equivalent positions in 2004 (which were the most recent data that I had around 2009 when I was writing the book) yields an advantage of 17 to 1 only.

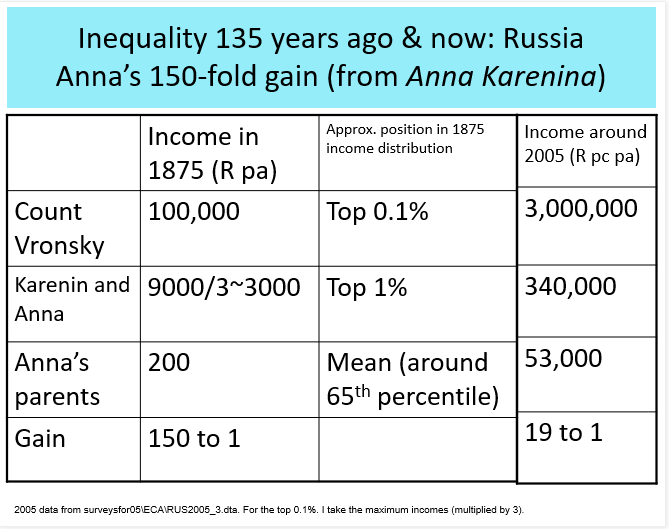

I decided also to include the story of Anna Karenina in the second vignette of “The haves and the have nots”. Her social trajectory is fairly similar to Elizabeth’s. We learn from just one Tolstoy’s sentence that her family was around the middling income status. With her marriage to Alexei Aleksandrovich Karenin, with whom she lives in a palatial home, she moved up to the top 1%. But with Count Vronsky, not unlike Elizabeth with Darcy, Anna moves to the rarefied circle of the extremely wealthy, belonging to the top 0.1% of Russia’s income distribution around 1875. Her lifetime gain was 150 to 1, that is, even more impressive than Elizabeth’s.

I then considered adding Balzac’s “Le Pere Goriot” which I liked a lot and which was much admired by Marx (see “Karl Marx and World Literature” by S. S, Prawer) precisely for his impitoyable depiction of financial capitalism in France. I collected lots of data, but then decided that adding a third very similar vignette may be a bit of an overkill. So I left it out. (A few years later, Thomas Piketty employed a similar technique in his “Capital in the 21st century” and drew heavily on Balzac.)

Now, Daniel Shaviro in his new and exciting book “Literature and Inequality: Nine Perspectives from the Napoleonic Era through the First Gilded Age” has expanded this approach to three epochs and nine books. In the first part of the book (England and France during the Age of Revolution), Shaviro discusses with the same objective of retrieving the facets of social and economic inequality, but in much greater detail than I, Jane Austen (“Pride and Prejudice”), Balzac (“Le pere Goriot” and “La maison Nucingen”) and Stendhal (“Le rouge et le noir”). In the second part (England from the 1840s to the start of the First World War) Shaviro looks at Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope and E M Forster. Finally, in the third part, he trains his gaze on the US Gilded age (Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner, Edith Wharton and Theodore Dreiser). I will review Shaviro’s book in my next post.

Read the entire blog post at globalinequality.com.