August 18, 2025

This is the conclusion of Stone Center Senior Scholar Paul Krugman’s series “Understanding Inequality,” which originally appeared on his Substack newsletter.

By Paul Krugman

On June 1 I published what I said would be the first of two primers on rising inequality. But I kept finding more things that I felt needed saying, so it turned into a six-part story arc.

The good news is that I believe that I’ve finished that story arc, at least for now, with the last two posts. Part V showed how predatory financialization has helped create extreme wealth. Part VI examined how wealth is converted into political power. And that was supposed to be it, for now.

But given the topics of those last two primers, it seemed to me that I should close out with an in-the-moment case study: A discussion of the rise of the crypto industry, which can be seen as a sort of hyper-powered example of predatory finance, influence-buying, and corruption.

I’ll discuss the following:

- The (strange) economics of cryptocurrency

- Crypto as a form of predatory finance

- How crypto drives inequality

- How the crypto industry has corrupted our politics

The economics of cryptocurrency

I still sometimes see people conflating the case for cryptocurrencies with the general case for a digital monetary system. The truth, however, is that our monetary system is already largely digital. Your bank account consists of ones and zeroes on the bank’s server, not a pile of cash in the bank’s vault. Most people use physical currency, if at all, for a handful of small transactions. Even writing checks has become increasingly rare. Instead we use debit cards and payment apps, which are simply ways to transfer ownership of some of those ones and zeroes.

In case anyone brings it up: Yes, there’s still $2.3 trillion in cash out there. But more than 80 percent of that is $100 bills, which are almost unusable in daily life, and are presumably being hoarded, largely outside the United States, rather than used in transactions.

So what does cryptocurrency add? Conventional banking, even when digital, rests on personal ownership: You, and only you, have the right to dispose of funds in your account. Most of the time your bank may consider knowledge of your PIN code or your CVC adequate proof of identity, but if the bank’s software flags a transaction as suspicious the bank may demand that you verify your identity in other ways.

With crypto assets, your identity doesn’t matter. If you have access to a numerical key identifying a Bitcoin or other digital coin, a key validated by the blockchain, it’s yours, period. Nobody even needs to know who you are. In fact, Bitcoin was originally envisaged as a tool that would allow decentralized trading, no need to deal with banks or other central institutions.

Cryptocurrencies have been around for a surprisingly long time. Bitcoin, which started it all, was introduced in 2009. In the early days crypto boosters asserted that using blockchain keys rather than having banks verify customers’ identity would reduce transaction costs, and that crypto would largely displace conventional money as a means of payment.

That didn’t happen. In his book “Number Go Up: Inside Crypto’s Wild Rise and Staggering Fall,” Zeke Faux noted that

Traveling around the world investigating crypto had given me a new appreciation for my Visa card. It worked instantly, with just a tap, charged no fees, and never asked me to memorize long strings of numbers, or to bury codes in my backyard.

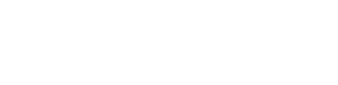

It’s not just Faux. The annual Federal Reserve survey of households’ well-being shows that very few people use crypto as a means of payment. The table shows that only 1%-2% of the households surveyed used crypto to make a payment or transfer funds. If they bought crypto at all, it was as a speculative investment. Moreover, the table shows that even this meager use of crypto by households has been falling:

Given its original promises, then, crypto has been a bust. Yet the value of crypto assets has surged to more than $3 trillion in value. This surge has probably significantly increased the concentration of wealth at the top. Not surprisingly, the crypto industry has acquired a lot of political power, although the sheer scope of that power is startling. How has this happened?

Crypto as predatory finance

In Part IV of this series I noted that a key part of the rise in U.S. inequality since 1980 has been a surge in the share of national wealth controlled by the top 0.01 percent. In Part V I showed that much of the rise in extremely high incomes and wealth can be attributed to the financialization of the economy — that is, the enormous growth of the financial sector. Remarkably, it’s hard to see good economic reasons for the rapid expansion of the financial sector. Instead, a significant share of the growth of U.S. financialization seems to have involved predation: making money by selling investors financial products they didn’t understand, doing an end run around bank regulation and in so doing creating new risks that eventually fall on taxpayers or other victims. The financial crisis of 2008-2009 was, to an important extent, the end result of such predation.

Does crypto enable predation? Yes, in three ways.

First, crypto appeals to people who have very little understanding of economic fundamentals. They buy simply because crypto prices have risen a lot in the past and assume that this will continue. In part this reflects the “greater fool” phenomenon that always comes into play during asset bubbles: crypto investors assume that there will always be someone down the road who will give you a real asset (like dollar assets or real estate) for your extremely high-priced ones and zeroes. And as revealed in the Samuel Bankman-Fried trial, crypto coiners don’t want the general public to know that they goose their values by buying one another’s currency.

Moreover, for many crypto investors there is a significant addictive element: the psychology of crypto investing is essentially the same as the psychology of gambling. Crypto is now so easily available and marketed so heavily — for example, sold in supermarket kiosks, pushed by payment apps like Venmo — that it has become the modern equivalent to the traditional numbers racket.

Second, as the Federal Reserve survey shows, crypto has failed to deliver on its promise that an anonymous payments system is superior to conventional banking. But there’s an important exception: crypto is extremely valuable in making transactions in which anonymity is very valuable for its own sake — namely, illegal activity. Crypto has few if any legal transactional uses, but it’s very useful if you’re laundering money and engaging in extortion.

Yet even extortionists, drug dealers, weapons dealers and financiers of terrorists dislike the extremely volatile prices of Bitcoin and its early emulators. They want to know how much a blackmail victim’s payoff will be worth in dollars when it arrives.

The solution to the extreme volatility of crypto is stablecoins: Digital tokens issued by institutions that (purportedly) hold adequate reserves in conventional assets, typically U.S. Treasury bills, and promise to keep the dollar value of their tokens fixed in dollars. The biggest stablecoin is Tether, which promises to maintain the value of each Tether coin at $1. Not surprisingly, it is also the leading cryptocurrency for illicit activity, including financing terrorism. Here’s how The Economist reported on Tether’s role just a few days ago:

But wait, there’s more. Leaving aside the unsavory uses to which stablecoins are put, stablecoin issuers create new systemic risks to the economy. For an institution that sells assets which it promises to redeem for dollars on demand is essentially a bank. Banks are subject to extensive regulation, in an attempt to limit risks to financial stability such as bank runs. Yet, in its pursuit of profit, the financial industry is constantly trying to do end-runs around these regulations – witness how Lehman Brothers took down the entire financial system and imposed trillions of dollars in cost. So, in the end, stablecoins are in effect offloading financial risk onto taxpayers. Yet another form of financial predation.

So there is a very good case to be made that the crypto industry is essentially a predatory enterprise. What can we say about how crypto affects inequality?

Crypto and inequality

In my primer on the rise of U.S. oligarchs — the extremely wealthy individuals who are exerting disproportionate political influence — I noted that there have been two phases in the rise of the super-wealthy. In the first phase, from 1980 until the early 2010s, the big fortunes were primarily made in finance. In the second phase, which we’re currently in, megafortunes have largely flowed from quasi-monopolies in technology.

Where does crypto fit into this picture? Blockchain is a clever technology applied to financial transactions. So you might expect that it would become a new source of extreme wealth. And it has. Forbes reports that there are currently 17 crypto billionaires. That’s a lot given the reality that crypto still plays virtually no role in legal economic activity.

A few of these billionaires, notably the Winklevoss twins, made their money by being early investors in Bitcoin and other non-stablecoin crypto assets. However, most of them became rich by founding or operating institutions that manage crypto: holding coins for people unwilling or unable to keep track of their blockchain keys. (So much for decentralized finance.) Four of the 17 made their money as shareholders in Tether.

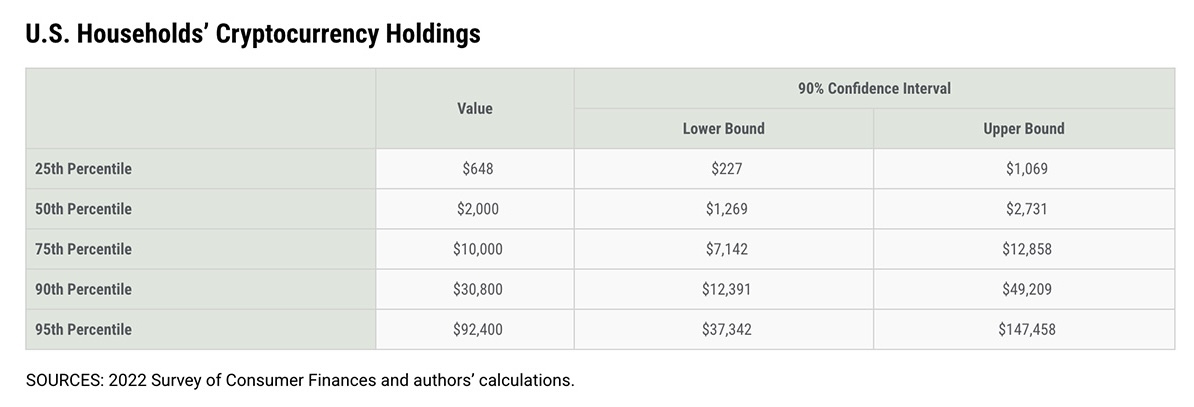

What about the capital gains accruing to investors who purchased crypto assets? Those who purchased early have seen big gains, at least so far. Information about the distribution of those gains is limited. What we do know is that while many people own some crypto, overall ownership is highly concentrated. Crypto ownership is almost surely more concentrated than total wealth, let alone income. Here are some estimates from the St. Louis Fed:

The bottom line is that the rise of the crypto industry has almost surely contributed to rising inequality in the United States.

But that’s not the reason I decided to include a discussion of crypto as a sort of post-credits scene for this inequality series. What caught my attention was the extraordinary amount of political influence crypto has acquired. The industry offers a sort of master class in how money can buy power in America.

How crypto bought the government

Back in 2019, during his first term, Donald Trump denounced crypto, on surprisingly sensible grounds:

I am not a fan of Bitcoin and other Cryptocurrencies, which are not money, and whose value is highly volatile and based on thin air. Unregulated Crypto Assets can facilitate unlawful behavior, including drug trade and other illegal activity….

Since then, however, he has become an enthusiastic crypto advocate, reversing the Biden administration’s fairly modest efforts at regulation and promising to make America a “Bitcoin superpower.”

On June 16, 2025 the Senate passed the GENIUS Act by a vote of 68-30. The bill purported to establish some regulatory oversight of stablecoins but in fact did little to address real concerns. Instead, the legislation was universally viewed as a huge victory for the industry, which received legitimacy, in effect a federal imprimatur, while giving up nothing substantive.

And 18 of those Senate votes came from Democrats.

How did a scandal-plagued industry, whose role in facilitating criminal activity is well known, achieve this triumph? Through the power of money, in the form of both campaign contributions and personal payoffs.

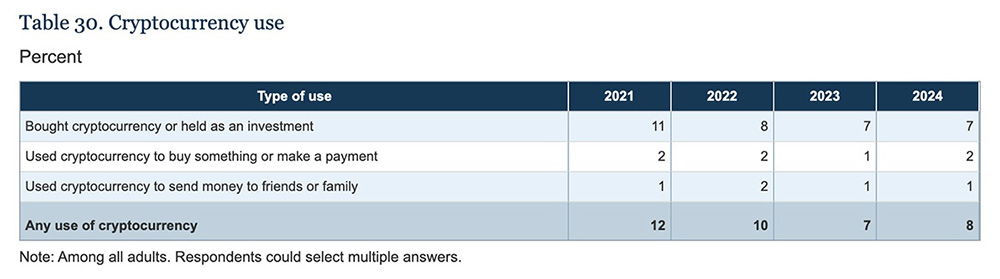

You may recall from my primer on money and power that the Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling made it possible to create super PACs that funnel large amounts of special-interest money, some of it “dark,” into elections. As the campaign spending tracker OpenSecrets reported, three huge super PACs backed by the crypto industry spent huge amounts, mainly on Congressional races:

Candidates from both parties received contributions, with only a modest tilt toward Republicans. But note the large spending against Democrats, with a small amount against Republicans. These took the form of attack ads against candidates who had been critical of crypto, while pro-crypto candidates received large donations. Some of the most critical spending took place during the primaries. Notably, crypto super PACs spent a huge amount to defeat the bid of Katie Porter, a crypto skeptic and rising star, for the Democratic Senatorial nomination in California:

The crypto industry’s political intervention was hugely successful: The candidate backed by the industry won in 53 out of 58 races. Politicians of both parties got the message: Don’t get in crypto’s way.

That was the campaign. What has happened since is even more striking. In my last primer I noted that there have long been personal payoffs to industry-friendly politicians and officials, who can benefit from the revolving door. But outright bribes were probably rare.

Crypto has changed all that. It’s true that part of the change reflects Donald Trump’s personal character or lack thereof, and more broadly the collapse of ethical standards within the Republican party.

But it’s also true that crypto has opened new frontiers in corruption. Perhaps surprisingly, the key isn’t the anonymity that makes crypto so convenient for criminals. Instead, it’s the fact that unbacked crypto assets, unlike stablecoins, can be created at will and have no fundamental value. So Trump could create a memecoin out of thin air, and people who want to curry favor with him can enrich the Trump family by buying the coin and driving up its price. Here’s a report that came out Friday, as I was working on this post:

Crypto billionaire Justin Sun is buying another $100 million worth of $TRUMP, doubling his total known stake of digital coins tied to President Donald Trump.

Sun, who founded the TRON blockchain and is working to resolve a civil fraud case with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, announced the purchase of the $TRUMP token in an X post on Wednesday. Sun said the Trump-linked digital coins will soon be tradeable on the TRON network.

″$TRUMP on TRON is the currency of #MAGA,” Sun wrote.

Do I need to say anything more?

Some senators proposed amendments to the GENIUS Act that would have blocked the use of crypto to enrich the president and his family. But they were rejected.

The thing is, the way crypto billionaires have purchased political power is essentially just an accelerated, souped-up version of the way America’s oligarch class as a whole has acquired so much power in a nation that formally gives every citizen an equal vote.

In an earlier post I quoted Woodrow Wilson: “If there are men in this country big enough to own the government of the United States, they are going to own it.”

What we’ve just seen in the case of crypto is exactly how that transaction works.

Read More:

- Wealth and Power. Paul Krugman, Understanding Inequality: Part VI

- Predatory Financialization. Paul Krugman, Understanding Inequality: Part V

- Oligarchs and the Rise of Mega-Fortunes. Paul Krugman, Understanding Inequality: Part IV

- A Trumpian Diversion. Paul Krugman, Understanding Inequality: Part III

- The Importance of Worker Power. Paul Krugman, Understanding Inequality: Part II

- Why Did the Rich Pull Away from the Rest? Paul Krugman, Understanding Inequality: Part I

- Paul Krugman’s Substack newsletter