June 17, 2025

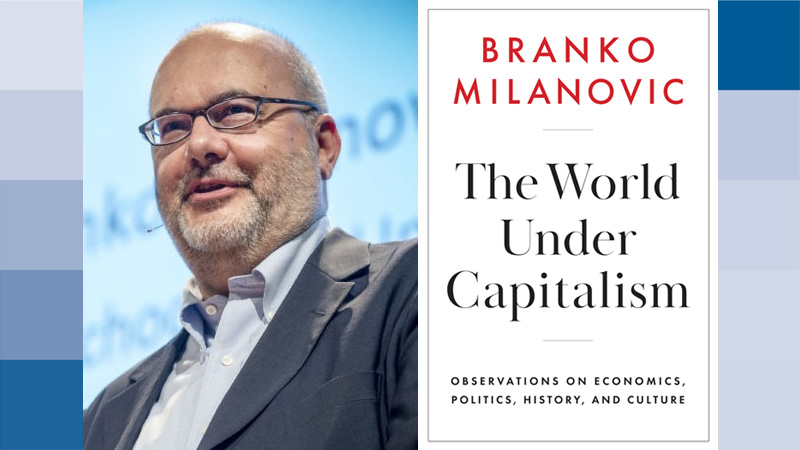

Du Passé Faisons Table Rase: An Excerpt from Branko Milanovic’s ‘The World Under Capitalism’

In the last decade, Stone Center Senior Scholar Branko Milanovic has published hundreds of short essays on his blog and Substack newsletter, Global Inequality and More 3.0, on topics including income and wealth inequality, economic thought, growth and climate change, and, of course, globalization. Some essays focused on a single country, such as Russia or China, or on a question related to culture or literature, like “inheritance, marriage, and swindle” in the novels of Jane Austen, Balzac, Dickens, and Mark Twain. He has addressed questions ranging from “Is Norway the new East India Company?” to “Is democracy always better for the poor?”, and offered his take on “How to dine alone…in a hyper-competitive world.” As Milanovic says in his introduction, he found writing these pieces to be “the most pleasurable” of all of his writing, including his many books and academic articles: “They were written on the spur of the moment, on a given topic, and at a single go. I would have an idea, which would come to me while strolling or reading, and I would then be seized by a burst of impatience to write about it and share it with others.”

In 2024, Milanovic gathered about 125 of these essays for The World Under Capitalism: Observations on Economics Politics, History, and Culture, published this week by Polity. In “Du Passé Faisons Table Rase,” the essay below, he looks back on his memories of the Serbian girl who escaped the Croatian government’s genocide during World War II and later worked for his family as a domestic helper — and why, as the French expression says, we might want to make a clean sweep of the past.

Du Passé Faisons Table Rase

By Branko Milanovic

I prepared dinner for myself tonight. I am now alone, in a house in Washington, which is about five times as large as the apartment in Belgrade where I grew up. At one point, we were five persons in that apartment. It means, I thought, that my living area had increased by 25 times. How did it happen?

Socially, I was born in what was called the “red bourgeoisie.” It has been a while since I wanted to write a post about how communism, at least in the Yugoslav variant, reproduced the class structure of capitalism, even if with a twist (less inequality). An important role in that discussion would have been played by a domestic help lady that my family employed from approximately 1960 to 1968. She was then, when she started working for us (“for us,” in communism!), about 25 years old. I cannot remember the names of people I met yesterday but I remember her name very clearly. I will never forget it. But, I realized, as I thought of writing about it, that it is not only the social issues that her memories brought to me, it was something else as well.

She was a Serbian girl, who had escaped from the Nazi-installed Croatian government’s genocide during the Second World War. I do not know how she survived or what happened to her parents or siblings, nor even if she had any brothers and sisters. (As you will see in a few paragraphs this is not surprising.) I would not have even known, so indifferent and willfully ignorant I was of her stories, that she was a Serbian genocide survivor, had I not remembered a short story she told us. The Ustašas would give little kids a small candy, and then, before they could put the candy in their mouth, they would strike their hands with whips so that the starved little children would both suffer from not having had the candy and would have their hands bloodied. This is the only thing that I remember. And most likely the only story she told us.

But why did we not know more? I think it was because my father, with his whole family murdered in the most brutal way by Serbian Nazi collaborators because they were communists, did not want to think about the past. He had had enough of killings after his family was murdered and he spent four years in German captivity. My mother, from a Serbian bourgeois family, was not particularly interested in the history of the poor people from Croatia, who barely escaped a genocide. But there was yet a deeper reason. We all wanted to forget about the past. We wanted to believe that the world had been created anew and whatever injustices and murders had been committed before would not be repeated. Everyone will get a fair chance. No one will be killed. In a traumatized country like Yugoslavia, where brother turned on brother, neighbor on neighbor, this was the greatest contribution of communists. Every nationality was guilty in one way or another, everyone at some point supported Hitler, so let us draw a thick line and not repeat the past.

This is what I think my parents and millions of others wanted to believe.

But other people did not want to draw a big thick line over the past. They wanted to find out who killed whom and when. And, while this was a worthy project, imbued — in some cases — with the idea that it would bring justice, I wonder if it had not encouraged another round of ethnic slaughter that began in the 1990s. In order to straighten our history, we, it seemed, had to relive it: perhaps with murderers and victims now reversed, but with killings still going on.

So, do people in America need now, when they drag statues down, new truth and justice commissions? Would truth and justice commissions bring justice or new bloodshed? I really do not know. A part of me believes that calling out past injustices is right and should be done. But another part of me believes that by never letting sleeping dogs lie, we may repeat history, even if with different people playing different roles. We may take Santayana’s advice upside down.

Some ten years ago I went to watch, on the opening day, Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained. It was a Christmas afternoon, a day for families, and for people to take their kids to the movies. In front of my family, in a Washington cinema, sat a Black family. The movie opens with a most frightful scene of slave torture: cutting limbs, beating, whipping. The poor mother and father in front of us precipitously grabbed their children and left the theater. Do you want your kids to grow up feeling that they are equal to everybody else, or do you want them to believe they are the offspring of people who were considered inferior and treated horribly? The family made the right choice. And I was overwhelmed with a wave of sympathy for them.

As Plato said, sometimes we have to have beautiful myths. Or otherwise we may have to relive our history. Which was not pretty.

Read the Book: