August 11, 2025

This is Part VI of Stone Center Senior Scholar Paul Krugman’s series “Understanding Inequality,” which originally appeared on his Substack newsletter.

By Paul Krugman

Market economies inevitably give rise to substantial inequality in income and wealth. Modern governments, however, have tools at their disposal, including but not limited to taxes and income transfers, that can mitigate inequality. In fact, all advanced-country governments do, in practice, redistribute income downward. As a result, post-tax-and-transfer inequality is lower than market inequality. As the chart at the top of this post shows, America’s Gini coefficient — a widely used measure of inequality — has consistently been lower for income after taxes and transfers than for pre-tax income.

Yet soaring U.S. inequality since 1980 hasn’t inspired a major government effort to counter that trend. In fact, policy changes, notably Republican tax cuts for the wealthy, have accelerated the growing disparities. And as I’ll explain later, the current level of inequality in America is much higher than what would be expected in a truly democratic polity, one in which all citizens had an equal voice.

Clearly, the economic elite possesses political power greatly disproportionate to its share of the electorate. Some readers are no doubt saying “Well, duh — everyone knows that.” Indeed we do.

Yet how, exactly, does this work? What mechanisms give the 1 percent and the 0.01 percent so much political power in the United States — especially compared with other countries? And why has their power increased in recent years?

I had planned to make this the last post in my inequality series. As it turns out, I’m going to need one more post to discuss recent extraordinary events involving financial and technology regulation. For now, however, let me focus on the general question of how wealth translates into power in a system that nominally gives every citizen an equal voice.

I’ll discuss the following:

- How we know that inequality in the United States is higher than it would be in a truly democratic polity

- The role of campaign finance

- Other forms of influence-buying

- The pervasive gravitational pull of big money

Inequality is too high

The U.S. government doesn’t do enough to mitigate income and wealth inequality. That may sound like a mere statement of personal preference, and I would, indeed, personally prefer a more equal society. But I’m saying more than that. We can show — quantitatively — that America has lower taxes on the rich and provides less aid to the poor than you would expect from any reasonably democratic political system.

Let’s start with taxes at the top. America has a progressive income tax, in which the marginal tax rate — the amount you pay on an additional dollar of income — rises with income. Currently, the marginal federal tax on the highest bracket is 37 percent. However, some states and cities have income taxes of their own in additional to federal tax. A high-earning resident of New York City, paying both state and city taxes, faces a combined federal and local marginal tax rate of around 52 percent. But the total marginal rate is much lower in most of the country.

Yet the top tax rate should be higher, probably between 70 and 80 percent.

How do we know this? Consider what would happen if we could somehow take $10,000 from an individual with an annual income of $2 million and give it to the median household, which has an income of about $80,000. The rich individual would hardly notice the loss while the median family would experience a significant rise in its standard of living.

So a democracy, which is supposed to represent the interests of the majority, basically shouldn’t care about the after-tax incomes of a small number of very-high-income people. It should, instead, treat the rich essentially as a source of revenue to pay for things that help ordinary Americans.

Does this mean that incomes above some high level should be completely taxed away? No, because we have consider the effects of high tax rates on incentives, both incentives to work and incentives to avoid or evade taxation. True, conservatives tend to exaggerate these incentive effects. After all, high-earning New Yorkers — Gordon Gekko’s working Wall Street stiffs — aren’t exactly famous for being lazy and working short hours. Still, the incentive effects are real. Putting together the available evidence on these incentives, a widely cited paper by Diamond and Saez estimated that the top tax rate that would maximize revenue is 73 percent. Other estimates are in the same ballpark or even higher.

That’s the top tax rate on earned income, mainly wages and salaries. What about other forms of income, such as investment income, capital gains, and inheritance? Without getting too deep into the weeds, similar arguments say that tax rates on other forms of income should also be much higher than they are.

What about the argument that high taxes at the top will discourage investment, innovation, and economic growth, maybe even reducing revenue? This is a zombie economic doctrine — that it, it should be dead in the face of vast amounts of contrary evidence, but keeps shambling along, eating brains, because it’s kept alive by the financial support of, yes, the wealthy. More about how that works later in this post.

One easy way to refute the claim that we must keep top tax rates low to foster economic growth is just to look at postwar U.S. history. We had top tax rates of 70 percent or more for a generation after World War II. That same period corresponded to a huge leap in living standards, never matched before or since:

What does the public think? For as long as this issue has been polled, a majority of Americans has believed that the rich pay too little in taxes, while only a small minority believes that they pay too little. Yet somehow Congress keeps passing big tax cuts at the top.

OK, so the rich pay too little in taxes. What about the amount of aid we provide to lower-income families? I personally feel that we should help our least fortunate citizens as a matter of basic decency, but that’s admittedly a value judgment.

What you may not know is that there are also powerful economic arguments for helping the needy. Aid to low-income families, especially families with children, has strongly positive long-run economic effects, because children who have had adequate health care and nutrition are much more productive as adults than children who haven’t.

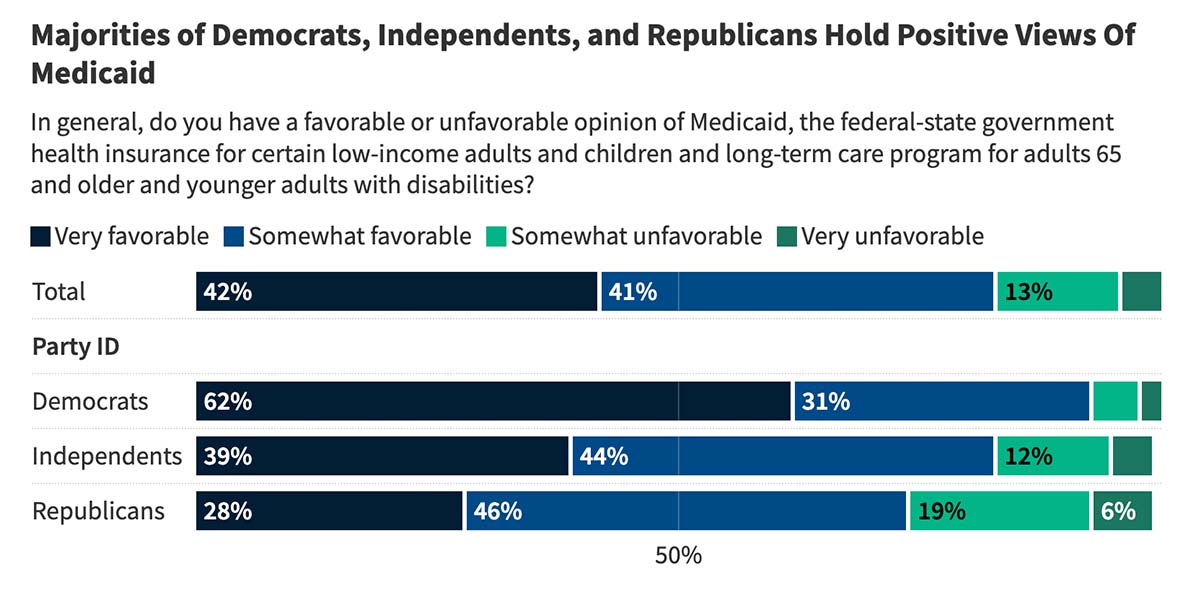

Furthermore, our biggest government program designed specifically to help lower-income Americans, and hence reduce inequality, is immensely popular: 83 percent of Americans, including a majority of self-identified Republicans, have a favorable view of Medicaid:

Yet the just passed One Big Beautiful Bill Act imposes savage cuts on Medicaid, so as to free up money for large tax cuts for the rich.

Clearly, a relative handful of wealthy Americans, constituting a tiny fraction of the electorate, have a great deal of political power. Where does that come from?

Political donations

Political campaigns in America have historically cost a lot to run. Mark Hanna, who ran William McKinley’s successful presidential campaigns in 1896 and 1900, reportedly said “There are two things that are important in politics. The first is money, and I can’t remember what the second one is.” Hanna is thought to have solicited $4 million in 1896, mainly from Gilded Age robber barons, to help defeat the populist William Jennings Bryan. Much of that money went to surrogate speakers and the distribution of campaign literature. As a share of GDP, Hanna’s outlays would be equivalent to around $7 billion today, roughly comparable to each party’s spending in 2024.

Where does the money go these days? A majority goes to media. Substantial sums also go to get-out-the-vote operations, operating campaign offices, and so on. Big spending on behalf of a candidate doesn’t guarantee victory. Elon Musk’s attempt to buy a seat on the Wisconsin Supreme Court was a flop. But money can definitely tilt the scales, and election victories by candidates with very limited money, like Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral upset, are rare. As a result, politicians have a strong incentive to be deferential toward likely sources of campaign funds — above all, wealthy individuals and big business.

It’s not hard to see how the logic of campaign finance can corrupt democracy, and there is a very long history of attempts to limit the power of money in politics — and an almost equally long history of attempts to remove or bypass these limits. The Tillman Act prohibited corporations from contributing money to federal campaigns in 1907 (!). The Federal Elections Commission, established in 1974 in the aftermath of Watergate, imposed strict reporting requirements while limiting the amount an individual donor can give to an individual candidate.

Over time, however, efforts to limit the political power of money have greatly eroded. The Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United undid the Tillman Act, declaring that from a campaign finance point of view corporations are people, with the same rights as individual donors, and that political spending is a form of free speech. Lower-court interpretations of the ruling also opened the door to the creation of “super PACS,” political action committees that can effectively raise and spend unlimited amounts, including from “dark money” groups that don’t disclose their donors, supporting or opposing political candidates. These super PACS aren’t supposed to coordinate directly with the campaigns they support, but I don’t think anyone believes that this is a significant restriction.

The United States is now unique among wealthy democracies in the extent to which it has allowed money free rein in elections. In France, for example, political TV ads are banned in the six months before an election. Corporate donations to candidates are banned. Individual donations are limited in size, and total spending by a presidential candidate in the final round of an election is limited to around $25 million — a tiny sum by U.S. standards. Britain also has limits on donations and total spending that are far below what U.S. campaigns spend.

Today, in the wake of Citizens United, U.S. elections take place in a financial environment Mark Hanna would have found familiar — and this environment definitely pushes politics to the right. The invaluable website OpenSecrets lists the 100 biggest donors in the 2024 election cycle, led, of course, by Elon Musk. Collectively they donated $2.4 trillion. Of that, 75 percent came from solid Republicans. And the top Republican donors were mainly radical hard-liners like Musk, Miriam Adelson, Ken Griffin, and Paul Singer. The top Democratic donor was Michael Bloomberg, who is solidly anti-MAGA but a former Republican and at best centrist on policy.

Money, then, talks very loudly through campaign finance. But that’s only one channel of its influence, and I suspect that the other channels are even more important.

Wingnut welfare

Many readers have probably heard about Project 2025. If you haven’t, it was an initiative by the Heritage Foundation, laying out a blueprint for a radical right-wing remaking of the U.S. government under a future Trump administration. During the 2024 election campaign, Trump and those around him denied any knowledge of or connection to Project 2025. Once in office, they began implementing the recommendations in its Mandate for Leadership almost verbatim.

What is the Heritage Foundation? It’s a lavishly funded think tank founded in 1973 to promote conservative ideas. Heritage releases very little information about its funding sources, but the investigative organization DeSmog has found that a large part of the funding for Project 2025’s advisory groups came from a handful of billionaire families with hard-right political leanings.

Heritage is just one of multiple institutions devoted to promoting a view of the world favorable to the interests of the very wealthy. These include an almost dizzying array of think tanks, with Heritage just the biggest. They also include media organizations like The Wall Street Journal’s opinion section (which often seems to live in a different reality from its still-solid news reporting.) The Washington Post, whose owner, Jeff Bezos, has declared that its opinion pages will promote “personal liberties and free markets,” appears to be headed down the same path.

These .01%-friendly institutions shape public discourse in at least two ways.

First, some people who aren’t necessarily committed to the right nonetheless take the “research” coming from these institutions seriously. I use the scare quotes because in every field I know anything about, everything coming out of Heritage is a steaming pile of … bad analysis. But politicians and ordinary citizens sharing material on social media don’t necessarily know that. Even mainstream media sometimes don’t seem to get it. During my early years at The New York Times, editors would sometimes send me Heritage reports and ask whether they refuted what I had been saying.

Second, these institutions help keep zombie ideas, like the claim that cutting taxes on the rich pays for itself, alive — by, in effect, providing zombies with a career path. There are always places at these institutions for self-proclaimed experts willing to advocate wealthy-friendly policies, a phenomenon some of us call “wingnut welfare.”

For example, the most prominent voice currently proclaiming the magic of tax cuts is probably Stephen Moore. Moore has repeatedly shown himself unable to get even basic facts right, but has had an apparently successful career at places like the Club for Growth, The Wall Street Journal and, yes, the Heritage Foundation. Donald Trump even tried to put him on the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, although he fell short thanks to a combination of doubts about his qualifications and personal scandal.

This array of institutions promoting ideas that serve the interests of the wealthy — call it the wingnut archipelago — is, I’d argue, as important in its own way as the effects of campaign contributions. They’re an important reason clearly false claims about taxes and deregulation remain in wide circulation. At the same time, solidly established analysis that doesn’t serve the interests of the wealthy, like the evidence for huge positive returns from aiding poor families with children, gets hardly any dissemination.

The gravitational pull of wealth

In 2003 Billy Tauzin, chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, played a key role in devising the Medicare Modernization Act, which added drug coverage to Medicare — but did so in a way highly favorable to both drug and insurance companies. Once the bill was passed, he announced that he would not run for another term. In 2005 he became the lavishly paid CEO of PhRMA, the pharmaceutical industry lobbying group, a position he held for the next five years.

Outright bribes to politicians and officials were probably rare until a few months ago (under Trump they’re now out in the open.) But the revolving door, in which officials who pursued policies friendly to corporations and the wealthy land lucrative positions as lobbyists, consultants, and members of corporate boards when they leave office, is very real. And it would be silly to deny that these opportunities — which are surely less available to officials who have advocated strong policies to limit inequality — have an important influence on policy.

Nor are former government officials the only people whose policy positions are affected by the gravitational pull of wealth. Quite a few economists serve on corporate boards, are highly paid corporate consultants, or both. True, unlike right-wing think tanks, businesses actually care about the competence of the people they hire. For the record, yes, I sometimes get paid to talk to business groups about the economy. But such gigs are surely less available to economists who crusade against rising inequality than they are to those who steer clear of the issue, which has a subtle but important effect on the overall discourse.

Finally, although this is hard to document, it has been obvious to me over the years that the wealthy — and successful businesspeople in particular — have outsized influence on policy in part because people assume that they must know what they’re talking about, even in areas that have nothing to do with their business. My friend Barry Ritholtz calls this the “halo effect.” I and other progressive economists lost some arguments, especially about taking a harder line with bailed-out banks, during the early Obama years. I would come back from these meetings saying, only partly in jest, that part of the problem was that the bankers had really good tailors, which made them seem more serious than disheveled academics, even if some of us had Nobel prizes.

The bottom line is that in addition to buying political support through campaign contributions and supporting institutions that promote right-wing ideology, great wealth distorts policy in other ways, ranging from the crude reality of the revolving door to subtler mechanisms.

What can be done?

Outsized wealth will probably always bring outsized power. In this primer I’ve tried to explain how this works in contemporary America, which is arguably even more of an oligarchy than it was in the Gilded Age. But the power of great wealth could be mitigated, in several ways.

First, we could restore effective regulation of campaign finance. It’s far easier to buy elections in America than in any other advanced democracy, and in fact far easier than it was here before Citizens United. It doesn’t have to be this way.

Second, we could strengthen countervailing institutions. In particular, unions used to be a powerful counterweight to the power of wealth in America, and still are in other advanced countries.

Finally, it seems clear to me that we’ve been in a vicious circle, in which extreme inequality has shifted policies in favor of the very wealthy, and these policies have fed even more inequality.

Reforms that limit the power of wealth could turn this into a virtuous circle in which reduced inequality reduces the bias of policy toward the interests of the 0.01%.

Obviously this is just the barest sketch of how we might turn this around. But this primer is already long, so I think I’ll stop here.

Read More:

- Predatory Financialization. Paul Krugman, Understanding Inequality: Part V

- Oligarchs and the Rise of Mega-Fortunes. Paul Krugman, Understanding Inequality: Part IV

- A Trumpian Diversion. Paul Krugman, Understanding Inequality: Part III

- The Importance of Worker Power. Paul Krugman, Understanding Inequality: Part II

- Why Did the Rich Pull Away from the Rest? Paul Krugman, Understanding Inequality: Part I

- Paul Krugman’s Substack newsletter