November 4, 2025

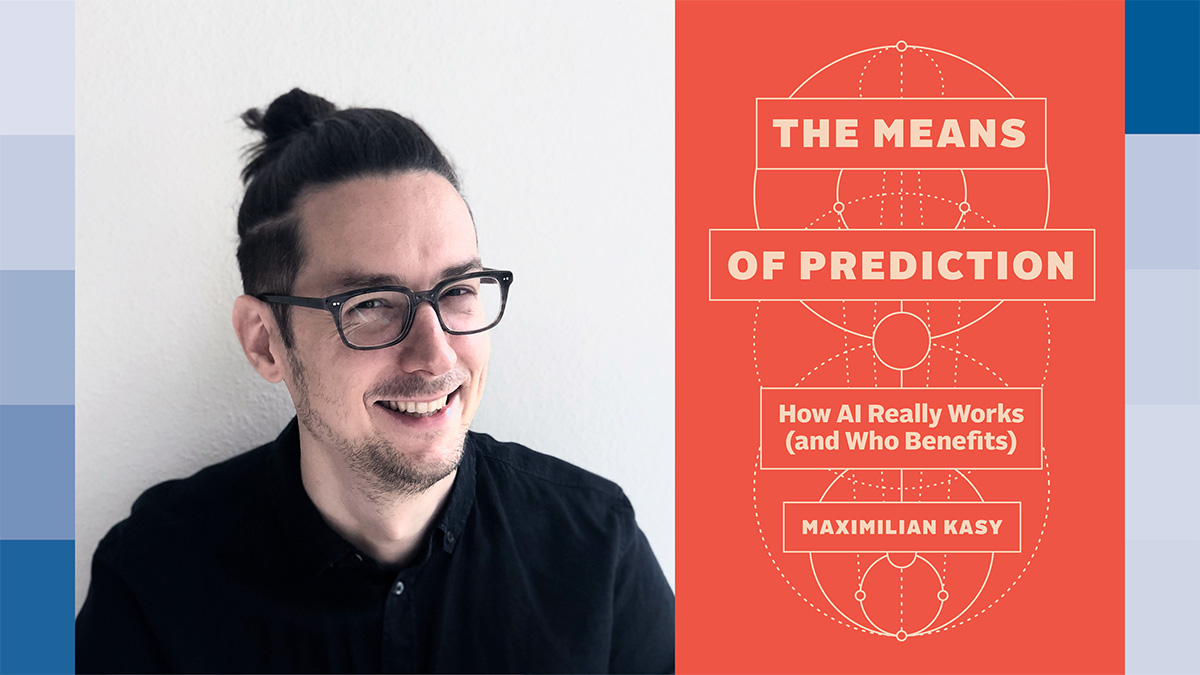

When Maximilian Kasy breaks it down, AI sounds simple — and that’s exactly his point. Kasy is both a professor of economics at the University of Oxford and an expert on machine learning, or the use of data and statistical methods to build automated decision-making systems. His just-published book, The Means of Prediction: How AI Really Works (and Who Benefits), provides a clear, methodical, and accessible understanding of artificial intelligence — which he defines as “the construction of systems for automated decision-making to maximize some measurable reward” — and offers a convincing argument for democratic control over AI’s objectives. Rather than seeing AI as something destined to destroy humanity, like “the machines” in The Matrix, or as so hopelessly complicated that the public and policymakers should leave the industry entirely in tech leaders’ hands, Kasy shows that the only truly scary question about AI is: Who controls it?

This interview with Kasy, who is also a Stone Center Affiliated Scholar and has written about AI for publications including The New York Times, has been edited for length and clarity.

You’re a professor of economics with a long-term interest in inequality. You also teach courses on machine learning theory. How did these interests come together in your research?

Kasy: It is a bit unusual. The topic of AI brought together these disparate interests of mine, and my backgrounds in different areas. As an undergraduate, I studied mathematics, and later I got a masters in statistics at UC Berkeley. I’ve also always cared about political and social issues, and for a long time, I approached these separately: on the one hand, working on inequality and political economy; on the other, doing more methodological work in statistics and machine learning.

I hope that this book can contribute something that not that many other books out there do, in terms of having a foot in the mathematical, technical side of the debate on AI, and one in critical social science and the broader debate around it.

Why do you call the resources that are required for AI — the data, computational infrastructure, technical expertise, and energy — “the means of prediction,” as in the title of your book?

Kasy: I think this title was one of my better shower thoughts. It’s of course an allusion to what Marx would call the means of production, and so the title is, by analogy, about the ingredients that are needed for producing AI. In making its automated decisions, AI is based on the analysis of a lot of data to make predictions — whether it’s predicting the next word on the internet for language models, predicting who will default on a loan in banking, or predicting what ad you might click on social media.

Prediction, and what is needed for prediction, is something that classical and modern statistics teaches us a lot about. Like: What’s the role of the data you need in order to learn something? What’s the role of computation or model complexity? What’s the role of different algorithms? A bit more indirectly, computation requires energy, which is also one of the key inputs for modern AI.

Those are the means of prediction that I talk about in the book, and they’re interesting for a number of reasons. They tell us what the potential is for AI in different domains, and about how much data could potentially be available. In particular, they tell us who controls AI, because the people who control the means of prediction are the ones who control the algorithms that are based on these means of prediction. It’s a question of who controls the computers, who controls the data, who controls the expertise. And what other players control similar assets, and what does that imply for how the political economy of AI is going to play out?

You seem opposed to “scary stories” about AI — the type of dystopian scenarios we often see in the media, entertainment, and even in academia. Why is that? What perspective do you think the general public should take when thinking about AI?

Kasy: In the opening of the book, I talk about two main camps: those that call themselves AI Doomers, and those that call themselves AI Boomers. Doomers believe that AI is soon going to reach superhuman intelligence, and then it’s going to take over and dominate us and eliminate humanity. The Boomers say AI is the last problem we have to solve, and it’s going to take care of everything from climate change to cancer, you name it.

The interesting thing is that both of these extreme stories are based on the same assumptions, and it’s very much the same set of people who believe one version or the other.

Technology is not fate. It involves decisions by humans and human institutions. We have agency around what’s going to happen. Technology is a means to an end, and that’s very explicitly true for AI, where pretty much all of AI is optimization. There’s some notion of a numerical objective that the AI is trying to pursue, some number that it is trying to make as large or small as possible.

It boils down to: Who gets to pick this number?

This is true in all the different domains where AI is applied. Anything from hiring algorithms, to trying to minimize the probability of employees unionizing at a company, all the way to algorithms used by ICE, built by Palantir, that target raids to deport undocumented migrants. And anything in between, like social media that decides what kind of news to show to us.

These are all algorithms that pursue an objective that someone had to pick. They aren’t something that happens to us; they are things that happen in the interests of certain actors.

But the interests of these actors might not be the same as the interests of society at large. There is a gap, potentially, between those two things. And the key issue then is how we can close the gap. The case that I’m trying to make is that the answer is democratic control by those who are being impacted by an algorithm. People should have a say over their own fate.

It’s not about whether Hal in Space Odyssey or Skynet in Terminator is going to come for us and we’re going to lose control. It’s that those are tools that are being used by certain actors, corporate or state actors or others, to certain ends, and we might or might not agree with their ends.

There isn’t a day when I don’t see an alarming story about AI, often focusing on whether it will soon exceed human intelligence and control us (possibly, to make paperclips). You don’t think there’s any chance we’ll have to face something like Hal or Skynet?

Kasy: I don’t think so. Fundamentally, that’s not how this technology works. It’s all built on optimization algorithms, and that can be a powerful tool, especially when it’s built on large data sets, but ultimately, it’s all about a number that some human picks. I think these stories where somehow the AI autonomously takes over and defeats us — that’s a story that serves certain interests, by hiding the fact that that there’s a Wizard of Oz behind the veil.

It does seem that AI is portrayed as a complex technology that the average person couldn’t possibly understand, and that this portrayal benefits the owners of AI.

Kasy: That’s very much part of the story. There’s this kind of technocratic thing of: Oh, it’s super complicated, just leave it to the experts, and the experts just so happen to sit in the big tech companies. In the interactions between many policymakers around the world and the tech companies, how it’s playing out is that the tech companies are basically telling policymakers: We’re the smart guys. Just leave it to us. You need us to protect you.

And that’s a story, of course, that takes away political agency from those who are supposed to represent the wider public.

And it’s a false story. There are many details of the technology that are complicated, and there are constant developments, but the basic ideas are not that complicated. Which, again, boils down to a number, like number of times somebody clicks on an ad on Facebook, or the number of people that get deported by ICE, or whatever that particular actor wants. Sure, there are some details under the hood that we might not all dig into, but the outline of this technology, what it does and what it’s designed to do, is very broadly accessible. And it’s something we need to discuss in order to steer the technology in a beneficial direction.

In the book you say that the most important question for AI must be: “Who gets to pick the objective?” In addition, you argue that the objective should be “maximizing social welfare.” Can you discuss why?

Kasy: Social welfare is a very generic term for things that we should want as a society. And economists, political philosophers, and others have spent a lot of time trying to elaborate how exactly we should define social welfare. But I think that the general point is that there’s some notion of what’s good for the society at large.

And that might often be different from what specific actors want, whether it’s specific corporations or specific state agencies, like ICE or Facebook. So the questions are: How do we close the gap, and who gets to close the gap?

I don’t think there are simple answers. There are popular answers that are clearly too limited. One of them is just basically around the notion of ethics, which is: Let’s just add some ethics courses to the computer science curriculum so that the engineers have a better sense of ethics, and then they are going to take care of making AI good.

That’s not enough, but it is something we often hear — essentially, that industry should self-regulate and it will do the right thing. But it’s not enough, because fundamentally, these are profit-maximizing corporations, the Silicon Valley tech companies. The ultimate goal, say, of Facebook is to maximize profits, and a large chunk of that is ad revenue. You might have the best intentions, personally, of not causing disruption to the democratic process or not harming teenage mental health. But good intentions alone won’t save us, because ultimately the goal is to sell ads in order to make profit.

The case that I would then make is to say that we, as people who care about the impact of AI, need to think about how we can turn AI into a better direction, and speak to all kinds of actors, and not just AI engineers. That’s a whole range of people who have different levers and different interests that could help with that. It’s anybody from the click workers who are training their AI, to the gig workers who are subject to AI decisions, to consumers who have leverage over the companies whose products they use. I think we should speak to all of these people, and not just narrowly to a slice of engineers and tech companies, when we think about how we can steer AI.

Do you think it’s possible in these polarized times to reach a consensus on ideas like “public control of AI objectives” or on the “democratic means” that should be employed, as you discuss in the book? How do you see making this possible?

Kasy: Things are polarized, and AI and the internet might have parts in that. In some sense, yes, it’s hard if you just debate the question: Should Facebook show more pro-Trump ads, or do more fact-checking? But if you break this down to the many different domains where AI is being used — in the workplace, at your local school, in your local police department, and so on — then I think there’s less partisan polarization. Giving the people — the ones who have an actual stake in what the immediate impact of the algorithmic decisions are — a real sense of agency and control over what’s happening could potentially have a big impact on political polarization, and on attitudes against existing democratic institutions.

I believe that a lot of the things that ail democracy in many countries at the moment are driven by a real sense of not having agency over our fate. Some of that might be ideological, but I think a lot of that is also real. And I think one of the important answers to that is giving people real agency over what’s happening to them. And one slice of that, and an increasingly important slice, is giving people agency over what happens in terms of AI systems taking over our lives and making automated decisions. The spread of AI could play out as a real loss of agency, where the machine decides you’re not going to college, you’re not getting this mortgage. Alternatively, we could have people getting together and saying: What should this school achieve? What should the policing patterns try to achieve? And have a real debate by the people who are being impacted.

Do you think there should be a democratically controlled agency that enforces rules on the owners of AI technology?

Kasy: I would say we need a multi-stage process, where first we think about all these different actors in society who have leverage and who can shift things. That’s kind of the short- and medium-term process. But ultimately, we want to build institutions and laws that institutionalize democratic control over these technologies at the level at which they impact people.

Probably laws could require some combination of two things. The first is transparency. It should be a fairly easy thing to implement — to say that anyone who runs an automated decision system should disclose the objective of that system. Facebook would have to say: We are maximizing ad clicks. Or ICE could say: We are maximizing the number of people we are deporting. And then we can have a debate. Is that what we want as a society, or not?

That’s the first step, and then the second step would be to set up actual co-determination. That’s probably the harder one. It would involve setting up some form of democratic decision-making — I think citizens’ councils could be an interesting one, where you have a randomly selected set of people coming together and then debating this objective — and making possibly binding decisions about a change to the objective.

There’s a lot of precedent for this type of citizens’ council, going from ancient Athens to more recently in Ireland, where they had a lot of debates around marriage equality, abortion, birth control — very controversial topics in a highly Catholic country. They brought together 100 randomly selected people from the country, who for a year met with people from all sides in these debates. They debated, and then made a recommendation. In this case, they ended up recommending liberalizing measures on all of those issues.

The book discusses some parallels with what we’re seeing right now in the development of AI to the stage of “primitive accumulation,” which the UK experienced during the land enclosures from the Middle Ages to the 17th century, when formerly public land became private. Can you discuss that, and how it also relates to the environmental impact of AI?

Kasy: There’s the environmental impact, but there’s also, very importantly, the primitive accumulation of data and intellectual property. There’s a huge redistribution of power and wealth going on in terms of incorporating data sources, the training data used for AI models. Most obviously, with the large language models, which are trained, essentially, on the entire internet, which has, of course, the intellectual output of countless people. Anything from Wikipedia, to arXiv (where academic articles are uploaded), to news outlets like The New York Times.

What’s meant by primitive accumulation — again, a term from Marx — is this idea of accumulating capital or control over the means of prediction by, in some sense, pre-capitalist or outside-the-market means. In this case, that means appropriating the intellectual property of others.

Relatedly, there’s the environmental impact, which becomes increasingly important. The scale of these data centers is humongous and increasing by the day, and they’re consuming massive amounts of energy. We’re at the point where all the major tech companies are now investing in nuclear power startups to try to find new energy sources for their data centers. But a lot of that is fossil fuel-based, with its impact on climate change. Also, they need cooling water for their data centers, which has a big local impact. Because you need very clean water to run the cooling system, it has to be drinking water quality. In some communities, especially in not-rich countries where they’re building these data centers, they’re literally taking away the drinking water from communities, and leaving them without drinking water.

What if we can’t manage to do what you’re suggesting: to have people come together, and agree on some form of democratic control over AI’s objectives? If we can’t accomplish that, where do you see happening, in terms of AI’s impact on society in the next few years?

Kasy: I think in many ways it’s going to amplify things that existed before AI, in terms of a concentration of power, a concentration of wealth, and an undermining of democratic self-determination. We have very powerful technologies controlled by a small number of people, in ways that are fundamentally more far-reaching than many other technologies we’ve seen. And these small number of people can build systems that make automated decisions that impact all of our lives.

Read More:

- Stone Center Working Paper Series no. 109: Basic Income and Labor Supply: Evidence from an RCT in Germany

- Stone Center Working Paper Series. no. 89: Adaptive Maximization of Social Welfare

- Stone Center Working Paper Series. no. 67: Employing the Unemployed of Marienthal: Evaluation of a Guaranteed Job Program

- Stone Center Working Paper Series. no. 65: The Political Economy of AI: Towards Democratic Control of the Means of Prediction