January 17, 2024

Economist and Stone Center Affiliated Scholar Anna Stansbury works primarily on issues related to power and institutions in the labor market. But about five years ago, she started researching a topic that arose from her observation of her own profession: the lack of socio-economic diversity within the field of economics. Using data from the National Science Foundation, Stansbury, working with Robert Schultz, then a master’s student at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research, found that recipients of Ph.D.’s in economics in the United States are far more likely to have highly educated parents, and much less likely to be first-generation college students, than graduates of the fourteen other major Ph.D. fields.* They also found that among U.S.-born economics Ph.D. recipients, the lack of socio-economic diversity is even more significant. And the situation isn’t improving: graduates of U.S. economics Ph.D. programs have become less socio-economically diverse compared to other major disciplines for the last five decades, particularly in the last twenty years.

Stansbury, who is an assistant professor of Work and Organization Studies at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, recently spoke to the Stone Center about her study, which was published last fall in the Journal of Economic Perspectives.

Why did you decide to research this topic?

Stansbury: I’ve always been interested in diversity in the economics discipline, and that was initially not from a research perspective but from the perspective of being a woman in economics, and also being concerned about the lack of racial and ethnic diversity. I was at the Berkeley Graduate Student Summit for Diversity in Economics in 2018, and talked to Robert [Schultz]. Both of us noticed that conversations about diversity almost never touched on class or socio-economic diversity. That piqued my interest about whether this was a topic we should think about more.

And then Robert came across data that allowed us to examine this question. This was the first work I’m aware of that measured socio-economic diversity in the economics discipline and compared it systematically to other academic disciplines.

What surprised you the most as you started analyzing the data?

Stansbury: We had a prior hypothesis that economics would be below average compared to other academic disciplines on socio-economic diversity, simply because economics is also below average on gender and racial diversity. One would assume that the same kinds of barriers apply at least to some extent across all three axes of diversity. What surprised me was how stark the picture is for economics. As we document in the paper, among Ph.D. recipients — and particularly among U.S.-born Ph.D. recipients — economics has a far lower share of first-generation college students, and a far higher share of students who have a parent with a graduate degree, than any other major academic discipline. One anecdote that a lot of people find particularly striking is that among U.S.-born Ph.D. recipients, the share of first-generation college students in economics Ph.D. programs is slightly lower even than in art history or in classics Ph.D. programs. And art history and classics, of course, are typically considered pretty socio-economically elite disciplines.

One thing I should emphasize is that the metric of diversity on which economics stands out very positively is international or geographic diversity. Economics has one of the highest shares of non-U.S.-born Ph.D. recipients of any field.

In your paper, you say that two-thirds of U.S. economics Ph.D. recipients are from other countries. Why is economics so diverse in that one particular respect, and how does it affect socio-economic diversity?

Stansbury: Economics, math, and computer science all have very high shares of foreign-born Ph.D. recipients. I think it’s partly because these are highly quantitative subjects and not country-specific in their material. Compared to other social sciences, for example, economics is more quantitative, which enables people from other countries with different language skills or backgrounds to translate their qualifications to an American degree and get into a good American program. And a U.S. economics Ph.D. is relevant in other countries in a way that a Ph.D. in a social science that is more country-specific in its approach wouldn’t be.

In terms of how it affects the results on socioeconomic diversity, foreign-born Ph.D. recipients on average have parents with less formal education, when compared to U.S.-born Ph.D. recipients. We use parental education as the measure of socio-economic diversity, so, if anything, economics being so international should push up our figures in socio-economic diversity. But overall, economics still has the lowest share of first-generation college graduates of any major Ph.D. field. When you break it out into U.S.-born and foreign-born separately, it looks even more stark, and that’s because of this different composition of U.S.- and foreign-born students.

Why has economics become even less socio-economically diverse in recent decades?

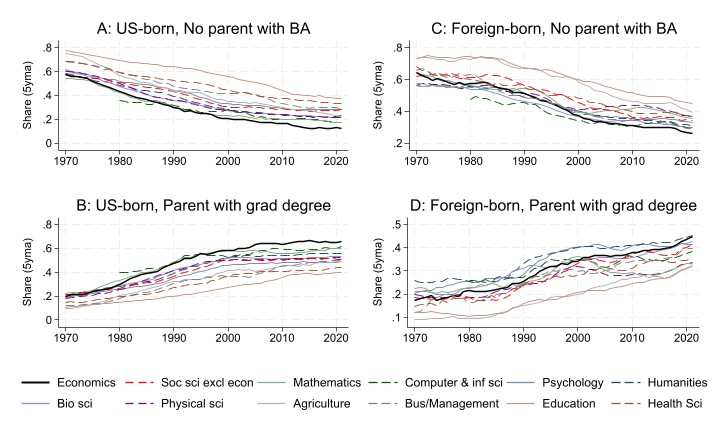

Stansbury: This paper doesn’t give definitive explanations. But we can look at the time series pattern for some clues. Our data, which start in 1970, show that from 1970 to about 2000, economics, math, and computer science diverged from other fields. They became less socio-economically diverse, relative to other fields, and they all moved together.

From 2000 to 2020, economics continued to get worse in terms of the socio-economic diversity of Ph.D. recipients, but math and computer science didn’t. (See Figure 1, below.) Those three fields, by the way, are also the least diverse on gender and race. There’s some set of factors that is making these three fields particularly difficult for underrepresented minorities, whether it’s gender, race, or socio-economic background, to succeed in.

Figure 1. Parental Education of U.S. Ph.D. Recipients over Time, 1970–2021

That’s increased over time, and it might be the increased mathematization of these fields. It might be that increased international competition is edging out people with less preparation, which often correlates with people from less advantaged backgrounds. It might be that these fields are doing less to provide a supportive environment for minorities. It could be a combination of those things. But since 2000, there’s been an economics-specific factor that goes beyond the other factors that are common to these mathematical, internationally competitive fields.

Do you think this can be traced at least partly to undergraduate programs?

Stansbury: One set of hypotheses is around why economics at the undergraduate level is relatively non-socio-economically diverse. The undergraduate economics major across the U.S. has a lower share of first-generation students than math or other social sciences — though, unfortunately, we don’t know how this has changed over time. Some of economics’ lack of socioeconomic diversity at undergraduate level seems to be compositional: economics is a larger major at more elite universities. And some of it seems to be that even within schools, students who take economics versus other majors are more advantaged. Part of that could be that at many schools, economics is quite a hard major to get into. Someone from a less advantaged background who had less high school preparation, particularly in a subject like math, might find it hard to get into the economics major.

But I think some of it is about how economics is taught, particularly at the introductory level. A lot of undergraduate students may feel that that the way introductory economics is taught is unrealistic, that it doesn’t really represent the questions and issues they care about. That might be particularly true for people from less advantaged backgrounds who may have personal or family experience of topics that are being talked about, like poverty, unemployment, or access to college, for example. A lot of the way that introductory economics is taught is quite simplistic in the assumptions it makes, and often quite un-inclusive in the language it uses — words like “low ability” or “unskilled” come to mind. All of this could, on the margin, put off students from less advantaged backgrounds who are interested in the topics we study but don’t like what they see of the approach that’s taken. But this is all speculative.

How do your findings about socio-economic diversity correlate with racial diversity and gender diversity?

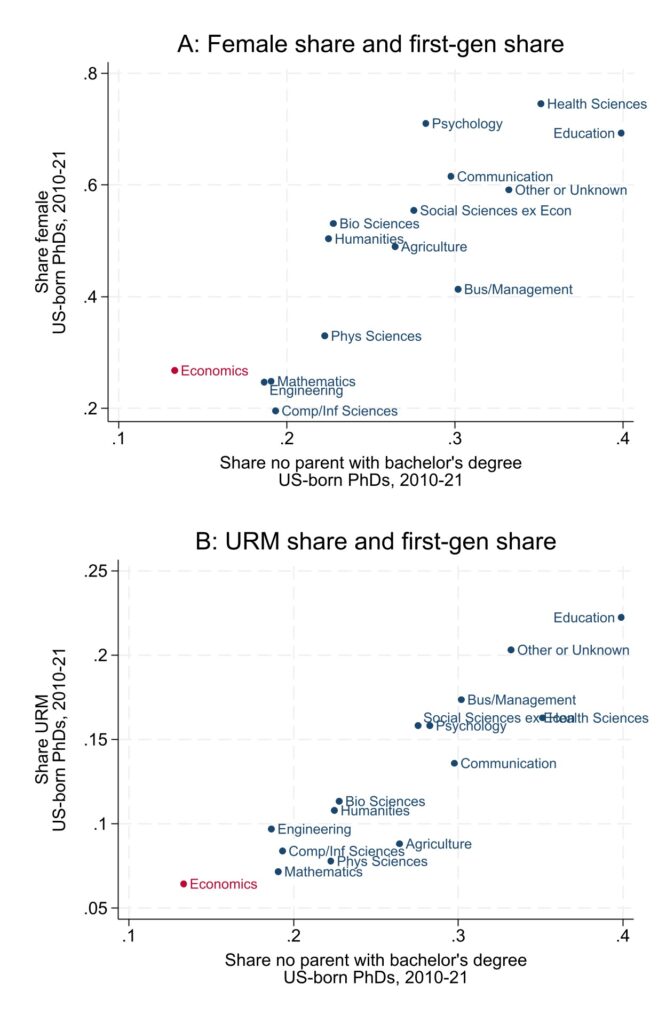

Stansbury: There are three headline facts about the relationship between socio-economic and racial diversity, particularly across fields. The first is that if you compare socio-economic and racial diversity across fields, they’re very correlated. Ph.D. fields with a low share of first-generation college graduates are also the fields, on average, with a low share of underrepresented racial minorities. And that’s measured according to the NSF as the share that is Black or Hispanic or Native American and Pacific Islander.

What this is saying is that the fields that are good on diversity in one metric are also good on diversity in the other metrics, and that the same kinds of factors seem to be preventing students who are less advantaged socio-economically or racially from succeeding or entering these fields. That’s fact number one. But fact number two is that the lack of racial diversity doesn’t explain the lack of socioeconomic diversity, and vice versa. One thing people will often say is, fact number one is true because, on average, Black and Hispanic Americans are from less socio-economically advantaged backgrounds. So if a field has fewer Black and Hispanic students, of course it will have fewer first-generation students. One would follow from the other. But that’s not the full story.

Even if you look within racial groups, Ph.D. economics programs still have the lowest share of first-generation students. So it’s not just that economics has fewer Black students, and Black students are more likely to be first-generation. It’s that economics has the lowest share of first-generation Black students compared to any other discipline, comparing only Black students. (See Figure 2, below.) Economics has the lowest share of first-generation Hispanic students, comparing only Hispanic students across fields. And within white students, and so on. So the race and class issues are correlated, but they do not explain each other.

Figure 2. First-Generation College Student Share, Female Share, and Underrepresented Minority Share, U.S.-Born Ph.D. Recipients, 2010–2021

Can you explain how this relates to comparisons to the population?

Stansbury: So this would be the fact three: when you analyze by race and class and not just one or the other, you can get a different sense of which groups are under- or over-represented relative to the population. Most of my paper is about economics relative to other fields. But a question that’s of interest to economics as a discipline is also: do we have a higher or lower share of women or Black Ph.D.’s than the underlying population? Economics has a very low share of Black Ph.D.’s. Part of that is that economics is bad relative to other disciplines, but part of it is that all of these subjects are bad relative to the overall U.S. population. The problem is Black under-representation in academia as a whole.

Economics Ph.D. recipients are about 30 percent women, so women are underrepresented relative to the population. If you compare race and class, what you see is that white first-generation college students who are economics Ph.D. recipients are still underrepresented relative to white first-generation college students in the national population. Overall, white people are overrepresented among economics Ph.D. recipients, but a white first-generation college student is underrepresented. In some sense, the race privilege seems to be canceled out or more than canceled out by the class dis-privilege, and therefore that group is still underrepresented compared to the U.S. population. And a Black first-generation college student is even more underrepresented than a white first-generation college student because of this intersectionality, this double disadvantage.

On the gender side, women Ph.D. recipients are underrepresented in economics, but women who have a parent with a graduate degree are actually overrepresented relative to their share in the population. It is important to increase gender diversity, but if you’re doing it purely by increasing women from elite backgrounds, you’re increasing gender diversity by worsening your socio-economic diversity. And you have to be aware of those intersections.

Why is socio-economic diversity, of all these different types of diversity, so important in this field?

Stansbury: I think there are three reasons. The first two are reasons why socio-economic diversity would be important in any discipline, and those are equity and efficiency. The equity rationale is obvious: if you assume that part of this lack of diversity is the result of barriers, then there are people who could be good economists, who want to be good economists, but who don’t end up becoming economists and that’s unjust. On efficiency grounds, if you assume that talent is evenly distributed across social groups, then there are a certain set of people who would be the best economists. By not creating the systems that enable them to become economists, we are losing out socially on those talents being matched to their best use.

The third set of reasons, which I think is particularly important in economics and other social sciences, is that we study topics that are particularly relevant to and important to people from non-elite backgrounds on the whole. We study how the economy works, and our insights inform our knowledge and our policies. If you believe, which I do, that people’s lived experience can inform the questions they choose to ask or the places they know to look for the answers or the hypotheses they may generate, then by missing out on people with this whole range of lived experiences as economic researchers, we’re missing out on potentially important knowledge, questions, and answers.

Studying unemployment, what determines unemployment, what its harms are, what kinds of unemployment policies are more or less optimal, what their effects are, access to education, access to healthcare, welfare benefits, policies that affect people in poverty, income distribution, and labor markets and hiring and unions, minimum wages — when 80 percent of U.S.-born economics Ph.D. recipients from the fifteen top-ranked Ph.D. programs have parents with graduate degrees, very few people have any personal or family experience of any of these topics. We’re probably missing out on a whole lot of insight that we could really use.

Do your findings suggest any ways to increase socio-economic diversity in economics Ph.D. programs?

Stansbury: This is more speculative, but one way is to improve diversity at the undergraduate economics major level. And there are two sets of interventions that seem to have worked quite well, and there’s actually randomized control trial evidence on this. One is to inform students what economists actually do. A lot of first-year students think that economics is about finance. Just telling students what kinds of topics economists study has increased enrollment in the first year introductory economics course disproportionately from first-generation students, from racial minorities, and from women. This increases diversity in three ways, and it’s very easy to do.

Less easy, but I think impactful, is ensuring that introductory economics courses are taught with an eye to inclusiveness, and to the kinds of interesting and nuanced analyses that economists actually do. Rather than starting with very unrealistic assumptions, get to the interesting, real-world nuanced problems and applications. There are now a lot of introductory courses that do this. The Big Data course at Harvard is one of them, and CORE Econ is another — they try to take these realistic assumptions and questions about inequality and poverty and other things that people come into economics caring about, and start answering them from Day One. I think that would be another way to get undergraduates into the major and keep them there.

And there are other things we can do. There’s been a big increase in mentorship opportunities and research assistantship opportunities that target women and underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities. Expanding those kinds of opportunities to first-generation college students would be another way to consciously build that pipeline, and we can do it in large part through the diversity initiatives we already have.

Note:

*See Table 1 of the study, available online.

Read the Study: