In this research spotlight, a study by Jaquelyn Jahn and her coauthors looks at how living in an area with high rates of incarceration increases the risk of preterm birth among Black and white women.

Incarceration has increased dramatically in the United States since the mid-1970s, a trend that disproportionally affects Black men and women. An important component is jails, sometimes called the “front door” to incarceration. Jails primarily hold people charged with committing a crime who are awaiting trial or other resolution of their case, and have been shown to cause serious psychological and economic stresses, ranging from the financial cost of bail to instability in income, employment, and housing. In recent years, public health research has begun to look at wider effects of incarceration — examining the effects of jail not only on incarcerated individuals but also on their households, extended families, and communities. A new paper, published in April in Social Science & Medicine, looks at the relationship between local jail incarceration rates and preterm birth among Black and white women.

The authors — Stone Center postdoctoral scholar Jaquelyn Jahn, along with Jarvis T. Chen and Nancy Krieger of Harvard University and Madina Agénor of Tufts University — linked newly available county-level jail incarceration rates compiled by the Vera Institute of Justice with individual-level birth certificate data among Black and white women in the United States. These linked data were then used to assess whether local jail incarceration rates increase the risk of preterm birth.

Infants born prematurely are at greater risk for mortality, developmental problems, and health disorders, and preterm birth has been shown to be influenced by stressors — both on the pregnant woman herself and on her social network. In addition, there are large, unexplained disparities in preterm birth rates between Black and white women in the United States. “Thus, it is conceivable that even if a pregnant woman did not directly know someone who was incarcerated, the social and financial support she is able to receive could be altered if her social network is impacted by incarceration,” the authors write. “Moreover, a county’s jail incarceration rate is reflective of policing and arrest practices, and anticipation of negative police-youth encounters may in themselves be a stressor for pregnant women, particularly Black pregnant women.”

The authors designed an empirical study to test their hypothesis that county-level jail incarceration is positively associated with preterm birth among Black and white U.S. women, the vast majority of whom (more than 99 percent) were not incarcerated during pregnancy. They also evaluated whether these associations changed between 1999 and 2015, a period during which jail incarceration rates rose. The authors applied ecosocial theory — which defines structural racism as explicit and nonexplicit laws, policies, institutional legacies, and indicators of racial injustice that become biologically embodied — in their analysis and examined whether inequities in Black and white jail incarceration rates are a predictor of preterm birth.

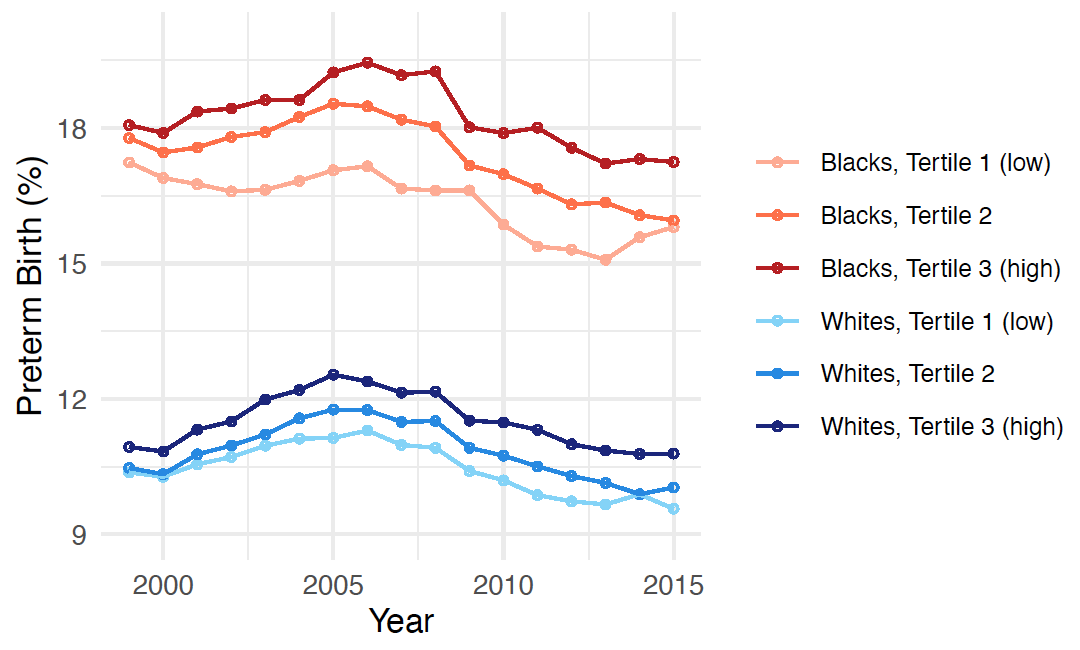

Their study showed that between 1999 and 2015, Black women had a higher prevalence of preterm birth, and that in every time interval, Black county-level jail incarceration rates were significantly higher than white incarceration rates. Among both Black and white women, the authors found that statistically significant increased odds of preterm births were observed in counties with higher jail incarceration rates throughout the study period. No statistically significant trends over time were found, however.

Figure 1. Preterm Birth Among Black and White Women Across Tertiles of Jail Incarceration Rates (1999-2015)

Their findings contribute to the small but growing body of scholarship on how structural racism might explain racial disparities in adverse birth outcomes between Black and white women. “Our results point to the importance of contextual impacts of mass incarceration for population health, and of integrating public health and criminal legal data to make such analyses possible,” the authors write. The higher chances of preterm birth associated with higher levels of county-level jail incarceration among both Black and white women suggest that prenatal-care outreach should be extended to include non-incarcerated pregnant women who live in counties with high jail incarceration rates. “Incarceration has health consequences that extend beyond those who are incarcerated,” the authors conclude. “Public health researchers and practitioners can have a role in monitoring and preventing these collateral consequences by linking criminal legal data with health data and by advocating for policies that lower incarceration rates.”