August 17, 2022

Lane Kenworthy is a professor of sociology and the Yankelovich Chair in Social Thought at the University of California-San Diego, and an affiliated scholar at the Stone Center. A long-term dedicated user of the LIS Database, he has published eight books and dozens of journal articles, and writes on his own site about topics ranging from voter perceptions to climate change. Kenworthy recently spoke to the Stone Center about his latest book, “Would Democratic Socialism Be Better?”

Does it surprise you that socialism is getting so much positive attention now, after so many decades of being seen in a negative light in the U.S.?

Kenworthy: If you’d told me 10 or 15 years ago that pretty soon a significant share of Americans would have about as favorable a view of socialism as they do of capitalism, I wouldn’t have believed it.

This probably is a function of three things. One is that we now have some time, some distance, since the collapse of communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, so there’s a generation of Americans who don’t have a deep-seated background dislike of socialism.

The second is economic conditions in recent decades, particularly slow income growth for people in the middle class and below, increases in economic insecurity, and rising inequality.

The third is Bernie Sanders’ use of the label “socialist,” especially in his 2016 campaign. He advocated the Nordic model, but he called it socialism, and most people don’t know the difference and have no real knowledge of the historical association of socialism with something else. So they thought, “Okay, if that’s what socialism means, it sounds pretty good to me.”

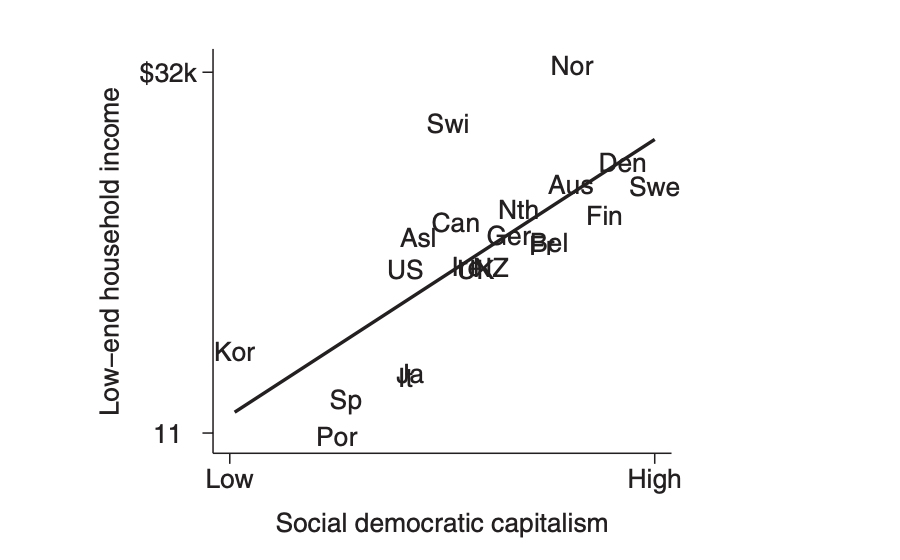

One of your charts (Figure 1.1, below) shows that the least well-off tend to have higher standards of living in countries that rely more on the Nordic model. How does the middle fare in those countries?

Kenworthy: In that graph I show income for households at the 10th percentile, which is pretty close to the bottom, and incomes at that point in the distribution are higher in the Nordic countries than in the United States. At the 50th percentile (the median), incomes aren’t higher in the Nordic countries. However, that doesn’t fully take into account the value of government-provided services — childcare and preschool, healthcare, transportation, and more. If we include these services, it’s likely that people in the middle have higher living standards in the Nordic countries than in the United States.

When you get to the upper middle class, living standards tend to be higher in the United States, especially if you don’t have children. Your salary is likely to be higher; pay compression in the Nordic countries not only pulls wages up at the bottom, it also pulls them down at the top. You pay less in taxes in the United States. You have good health insurance from your employer. You may not need childcare. So that’s one real tradeoff: if you’re upper middle class or rich, you probably have higher living standards in the United States.

Figure 1.1 Social democratic capitalism and living standards of the least well-off

Low-end household income: posttransfer-posttax income at the 10th percentile of the income distribution. 2010–2016. The incomes are adjusted for household size and then rescaled to reflect a three-person household, adjusted for inflation, and converted to US dollars using purchasing power parities. “k” = thousand. Data sources: Luxembourg Income Study; OECD. Social democratic capitalism: average standard deviation score on four indicators: public expenditures on social programs as a share of GDP, replacement rates for major public transfer programs, public expenditures on employment-oriented services, and modest regulation of product and labor markets. The data cover the period 1980–2015. Data source: Lane Kenworthy, Social Democratic Capitalism, Oxford University Press, 2020, pp. 39–40. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria. The line is a linear regression line. The correlation is +.73.

Could you discuss the point made by the Finnish journalist Anu Partanen, who, you say, found that the lack in the U.S. of “access to high-quality, affordable health insurance, childcare, housing in good school districts, college, and eldercare” actually “diminishes not only Americans’ economic security but also their freedom”?

Kenworthy: I think there are two key points here. One is the distinction between negative liberty and positive liberty. Negative liberty means there are few legal or regulatory impediments to my being able to do what I want. Positive liberty or positive freedom refers to my ability to actually do things. If I don’t have much education and wages are low and childcare is very expensive, my capability to succeed in the labor market may be quite limited.

The other point is that libertarians and conservatives who think of government as the main threat to freedom miss the fact that many Americans are dependent on family, friends, charities, or religious organizations, because we don’t have the level of public goods, services, and supports that the Nordic countries do — things like early education, paid parental leave, social insurance programs, low cost or free college, elder care. As a result, many Americans have to borrow money, or have to rely on their parents or maybe grandparents to pay for their kids’ childcare or college, or have to turn to charities when things go bad. Dependence on government is only one type of dependence.

In a democratic country, government probably is a more reliable source of support. First, it tends to be more comprehensive. Governments are more likely than churches or charities or friends or family members to provide a particular benefit or service or type of insurance to everyone who needs it. Second, the government is much more likely to always be there. It’s less likely to disappear like a charity might. It’s less likely to be unreliable, like parents or friends may be, because they’re unwilling or unable to provide the kind of support that large government public insurance programs or services can. So in a stable, rich democratic country, people who need help tend to be better off when those types of supports are provided through government programs.

This is a very compelling argument for social democratic capitalism, the label that you give to the Nordic Model. How do you think academics can extend their reach to the public? Is that something you hope to do more of — to have your research become part of the public discourse?

Kenworthy: I’m a social scientist, so I focus on trying to draw evidence-based conclusions. I do try to disseminate what I find in an accessible way, but I haven’t been as aggressive as I perhaps could in trying to reach the public. Mostly I write books (including an online book I call “The Good Society”). That isn’t because I think books are the most effective way to influence opinion. It’s selfish — it’s because I love writing books.

I was a fairly active blogger from 2008 to around 2013, but I stopped because I came to feel I was spending too much time reacting to current events. When invited, I write op-eds and do interviews and podcasts. But I’ve stayed away from social media. This, too, is for purely selfish reasons. For me social media would be a huge time-suck, and I already feel like I don’t have as much time to read, think, analyze, and write as I’d like.

You note that many high-income countries have moved toward social democratic capitalism in recent decades. Can you discuss how the U.S. has moved in this direction, which you call “its slow but fairly steady long-run movement toward social democratic capitalism”?

Kenworthy: Journalists, op-ed writers, and policymakers sometimes say Western European countries have welfare states while the United States doesn’t. That’s misleading. We don’t have national paid parental leave or early education, we don’t have a national sickness insurance program, and we don’t have a government guarantee of health insurance. But we do have most of the social programs that other rich democratic countries have. Our programs tend to be less comprehensive and less generous, but they do exist.

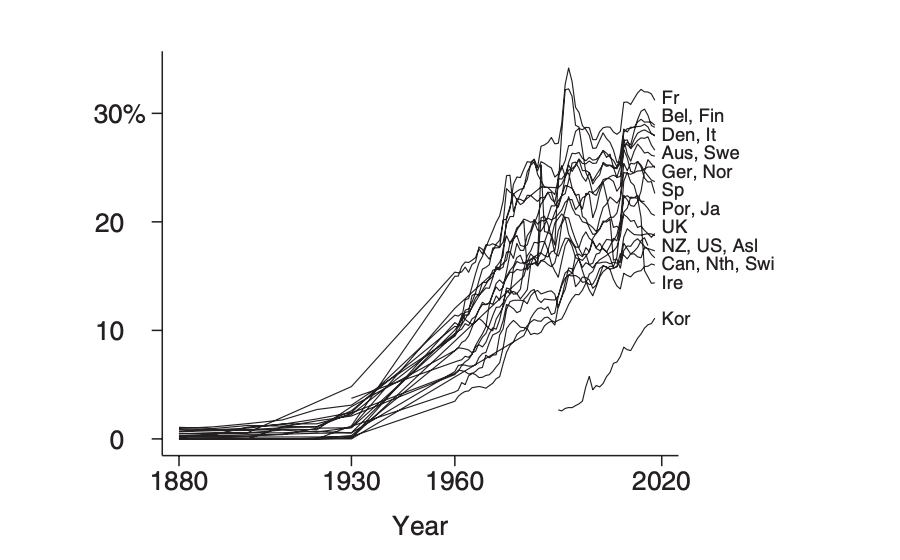

In fact, the contemporary American welfare state is closer to those of Denmark and Sweden than it is to the American welfare state of a century ago. The last graph in chapter one of my book (Figure 1.9, below) shows spending on government social programs as a share of GDP. Beginning around 1930, the lines go up for all of these countries, and that’s true for the United States too.

Figure 1.9 Public social expenditures

Share of GDP. Gross public social expenditures. Data source: Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser, “Public Spending,” Our World in Data, using data for 1880–1930 from Peter Lindert, Growing Public, volume 1, Cambridge University Press, 2004, data for 1960–1979 from OECD, “Social Expenditure 1960–1990: Problems of Growth and Control,” OECD Social Policy Studies, 1985, and data for 1980ff from OECD, Social Expenditures Database. “Asl” is Australia; “Aus” is Austria.

And spending has continued to rise, although at a much slower rate, in the years since 1980, when our policy orientation became more conservative or neoliberal. Even during this period of the past 40 years, we’ve seen expansion in the American welfare state. The Earned Income Tax Credit has grown steadily and is now a core antipoverty program. Medicaid has expanded incrementally. We’ve seen expansion of paid parental leave at the state level. A growing number of states, including some conservative ones like Oklahoma and Georgia, have added universal pre-K for four-year-olds. We’ve increased spending for disability programs. These developments haven’t been as momentous as the creation of Social Security and unemployment insurance in the 1930s or of Medicare and Medicaid in the 1960s. But they’re significant nonetheless.

The main subtraction during this period was the welfare reform in 1996, where we switched from AFDC to TANF, and states were given a lot more authority over provision of cash assistance to poor families. That very important form of social assistance has all but disappeared in some states. But when you weigh that against the expansions, I think it’s pretty clear that America’s social policy has continued to get more generous, just at a slower pace than was the case in prior decades.

You’re an author of 10 LIS working papers, going back 24 years. And that understates your engagement with the LIS data, given that much of your work appears in books. Could you discuss the role that the LIS data have played in your work?

It’s impossible to overstate the importance of the LIS data to my work. I think that’s true for many researchers who study income inequality and poverty, particularly those who want to compare across countries.

I’ve also increasingly been using the LIS data for analyzing living standards. If you want to, for example, compare income at the 10th percentile across countries, the LIS data are extremely useful. You can now do something like this with data from the OECD, but the LIS Database is my go-to source for comparing real living standards across countries and over time.

Read More: