Stone Center Affiliated Scholar Alexander Hertel-Fernandez is the coeditor, with Jacob S. Hacker, Paul Pierson, and Kathleen Thelen, of the recently published volume The American Political Economy: Politics, Markets, and Power. The book, published by Cambridge University Press, includes contributions from 19 political economists on the interconnection of politics and economics in the United States, and explores critical issues related to the country’s decentralized political institutions, the power of corporations and interest groups, racial inequalities on the local and national levels, and the knowledge economy.

Hertel-Fernandez is currently on leave from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) to serve as the deputy assistant secretary for research and evaluation at the U.S. Department of Labor. His chapter, posted below, examines the history of the American labor movement and argues that collective action can lead to meaningful public policy changes that can, in turn, increase the power of organized labor in the political economy.

By Alexander Hertel-Fernandez

The study of American political economy requires focus on a very different set of actors than does the conventional study of American politics as practiced by contemporary scholars. In particular, the core questions surrounding the American political economy call for a deep understanding of the preferences, power, and tactics of organized actors — and the ways that those organized actors both influence, and are influenced by, economic and political institutions. And within the universe of US organized interests, producer and class interests are especially relevant, encompassing labor, business, and increasingly, wealthy Americans that are collectively constitutive of the political economy. Such a political economy perspective contrasts with other approaches that either do not center economic interests or treat such interests as relatively interchangeable with one another.

In this chapter, I consider the development of the American labor movement, focusing closely on the intersection between law, collective action, geographic and territorial divisions of political authority, and labor’s political and economic power. A central argument of this chapter is how disruptive — and even illegal — collective action by workers can produce changes in public policy that entrench labor’s clout in the market and in politics.

Yet US public policies have also increasingly constrained the labor movement, and this chapter discusses the ways that early policy decisions fragmented American unions along both sectoral and geographic lines, with enduring consequences through present day. Indeed, a comparative analysis of labor law across rich democracies reveals that the division of American labor law across both sectors, but especially levels of government, is relatively unique. That fragmentation has weakened labor’s capacity to shape national politics and to take advantage of otherwise-favorable political opportunities.

Just as importantly, I consider how polarization, especially among donors, private-sector businesses, and activists on the political right, has fueled a backlash to the public-sector labor movement, aided by labor’s sectoral and geographic fragmentation. This backlash fused racial resentment in the mass public together with coordination among elite corporate and individual donors, reflecting a broader strategy within the contemporary GOP coalition (also described in our Introduction). The conservative counteroffensive against labor has also been aided by businesses’ advantages in cross-state advocacy, including state lawmakers’ fears of capital flight, another distinctive element of US federalism.

Taken together, this chapter underscores several major themes developed in the introduction to this volume, including the effects of territorial and geographic division of US political authority, long-term repercussions of political alliances between private-sector businesses, increasingly conservative activists, and right-leaning donors on US public policies, and the central role of the courts and the law for the nature of the US political economy.

What is distinctive about the American labor movement?

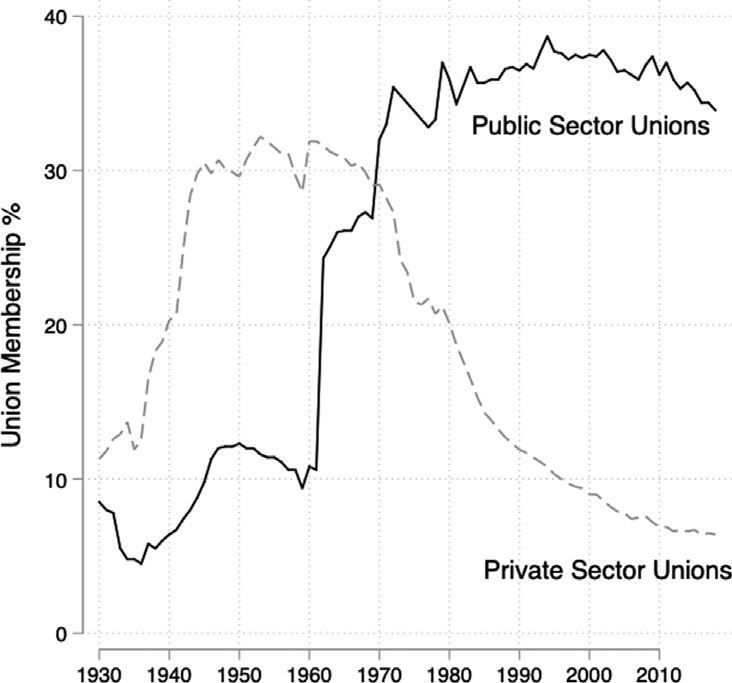

Figure 3.1 summarizes the historical development of unions in the United States, focusing on total union membership in the public and private sectors from 1930 through 2019. It illustrates three key facts about the US labor movement: (1) public-sector unions followed a very different trajectory than did private-sector unions, reflecting a separate legal regime and underlying set of political developments; (2) private-sector unions have been in steep decline since their peak in the 1950s so that membership in private-sector unions is now lower than it was before the passage of the 1935 federal law recognizing the right of private-sector workers to organize and bargain collectively; and (3) although membership in public-sector unions is currently substantially higher than in the private sector, government union membership rolls have been steadily declining since the 2000s.

Figure 3.1 The historical development of the US labor movement

Notes: Union density before 1972 from the Troy-Sheflin series reported in Eidlin 2018; Bureau of Labor Statistics thereafter.

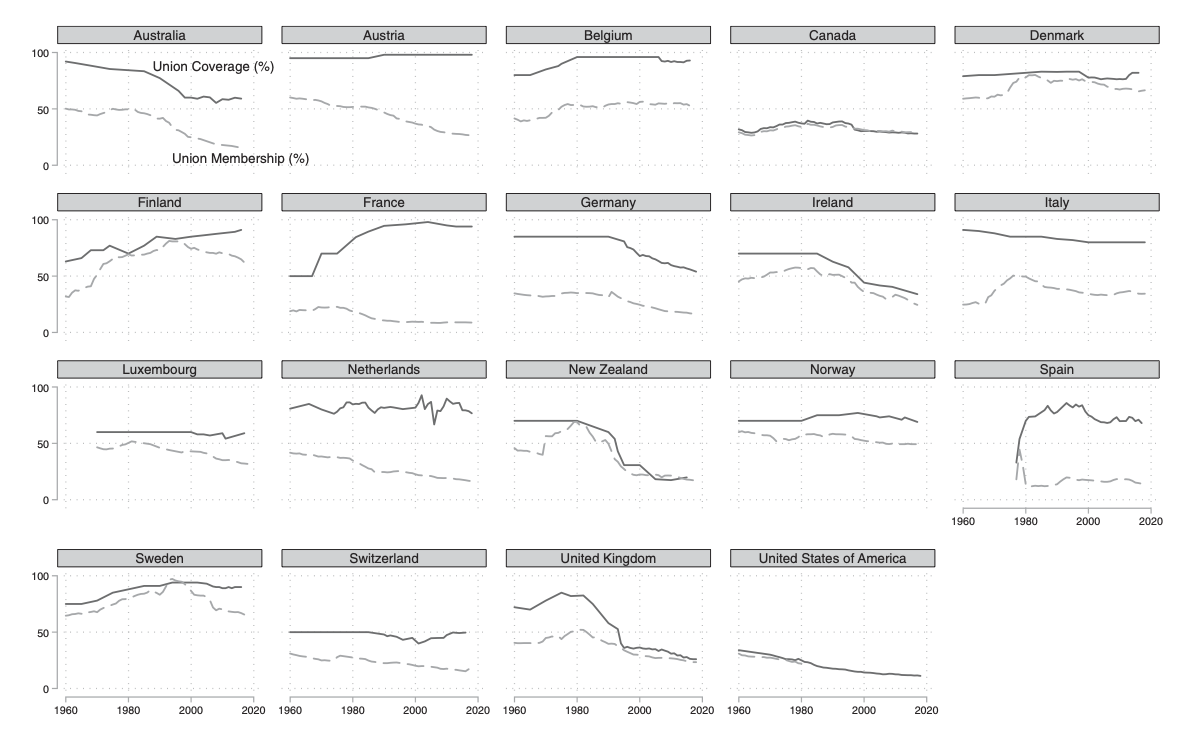

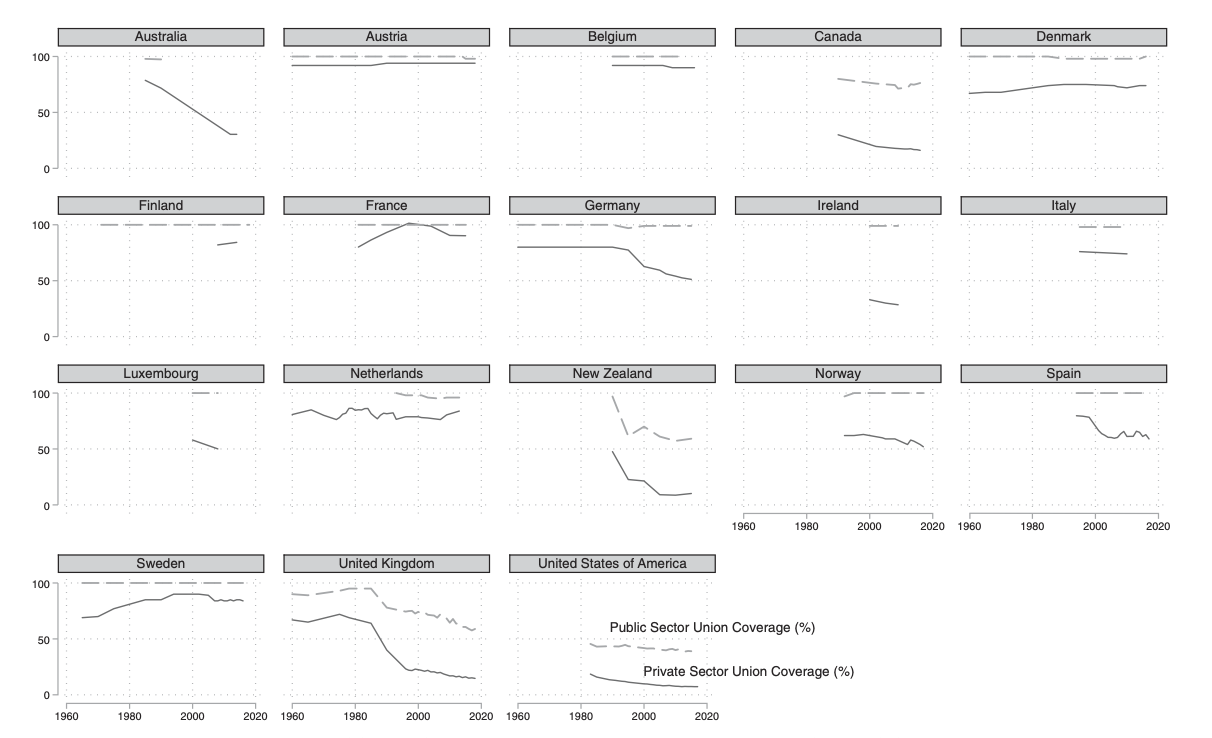

How unusual are these characteristics of the American labor movement? Figures 3.2 and 3.3 lay out the picture of similar trends in other advanced economies with data from the ICTWSS Database.1 Figure 3.2 plots trends in union coverage — that is, the proportion of workers covered by collective bargaining agreements — and union membership. Here the United States stands out for two features: not only are its union coverage and membership rates among the lowest of peer rich democracies, but unlike many other countries there is essentially no difference between its coverage and membership rates. That is because American labor law as enshrined in the 1935 National Labor Relations Act built a system of labor organizing and bargaining centered on establishments — individual plants, stores, or factories — rather than on companies as a whole, or even regions or sectors as in other countries, like Germany. As many other scholars have noted, this enterprise-based model of unionization has contributed mightily to the woes of the US private-sector labor movement (e.g., Andrias 2016; Naidu, this volume). Figure 3.3 compares union coverage rates in the public and private sectors. Again, the United States stands out as a relative outlier for its relatively low levels of both public and private-sector coverage. While other countries have different levels of union strength between the public and private sectors, few other countries have such low and declining levels of labor, particularly in the government sector. Only the United Kingdom and New Zealand exhibited similar drops in public-sector union coverage in recent decades — yet both the British and New Zealand government union coverage rates have stabilized at rates much higher than in the United States.

Figure 3.2 Union coverage and membership rates in advanced democracies

Figure 3.3 Public- and private-sector union coverage rates in advanced democracies

Why have unionization rates in the United States fallen so sharply, especially in the public sector? To answer that question, we can first look to the comparative data again to see what is different about the structure of American labor laws. What sets the United States apart from other rich democracies is not necessarily that it has separate laws governing public and private unions; many other countries treat government and private-sector workers differently when it comes to union recognition, collective bargaining, and strike rights. Rather, what makes the United States distinct is the low level of rights afforded to all workers as well as the institutional fragmentation of public-sector labor rights across subnational units.

Only one other rich democracy — Canada — delegates as much control over union rights to subnational governments as does the United States (OECD 1994). But even in Canada, union rights are more uniform than in the United States. Canadian teachers, for instance, enjoy collective bargaining rights (albeit with variable scope) in all thirteen provinces and territories, and at least some strike rights in eleven provinces and territories (Hanson 2013). By comparison, local governments are only required to bargain with American teachers in thirty-three states and teachers only have strike rights in thirteen states. American labor rights, especially in the public sector, are thus uniquely geographically uneven in comparative perspective.

Comparisons of government union membership across provinces and states tell a similar story (McCartin 2008; Walker 2014). In 2019, US public union membership rates varied from just 7 percent in South Carolina to 66 percent in New York — a 59 percentage point gap. Across the northern border, rates of public union coverage in Canadian provinces in 2019 ranged from 71 percent in Ontario to 88 percent in Prince Edward Island, a gap of only 17 points. What accounts for that uneven subnational development in the United States? To answer that question, we must return to the New Deal era, when the Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration enacted new legislation guaranteeing workers their first federal rights to organize and collectively bargain with employers in the 1935 National Labor Relations Act (or NLRA).

A stalled national labor movement in the New Deal era

The Wagner Act, as the NLRA was dubbed, reflected a series of significant compromises, setting in place a firm-centered organizing and bargaining model for American unions that ultimately restricted their reach and power, especially given recent changes in corporate governance practices (e.g., Andrias 2016; Andrias and Rogers 2018). Not only does the NLRA require unions to organize store by store or factory by factory, greatly increasing the costs of organizing an entire business or sector, but a firm-centered approach also raises employers’ incentives for fighting unionization efforts if they must compete against nonunion firms within their region or industry (e.g., Dimick 2014). Yet even in spite of these important limits, the Wagner Act offered what previous state and federal legislation had not: a federally protected national right to form and join a union and bargain collectively with employers.

In a testament to the law’s ambition, shortly after the NLRA passed employers began efforts to retrench labor’s hard-won rights to restore employer prerogatives in the workplace. In a series of landmark decisions, the Supreme Court began siding with employers to restrict the scope of the NLRA, especially on the issues of strikes and the “right to manage” (Pope 2004). No less important was a turn against labor in the mass public, most pronounced in the South but also present among Northern Democrats as well (Schickler and Caughey 2011). While it is difficult to isolate specific causes for the public’s souring on the labor movement, the timing of the shifts corresponded to an upsurge in labor militancy that the public viewed as illegitimate, especially in the run-up to the war. This dynamic points to a tension that the labor movement faced repeatedly throughout history: balancing the need for aggressive workplace actions that can amass political and economic power to secure changes in public policy against the risk of public backlash.

Although the Roosevelt administration and Northern Democratic leaders staved off the most significant efforts to curtail labor rights, Republicans, allied with anti-labor Southern Democrats, continued to use the resources of Congress to campaign against the labor movement and ultimately succeeded in gaining sufficient power in the 80th Congress to pass, over President Harry Truman’s veto, the 1947 amendments to the NLRA. Supported by businesses and anti-union conservatives in both parties, the Taft-Hartley Act imposed new federal restrictions on union activities, including strikes and boycotts, granted employers expanded rights to curb unionization drives, and excluded low-level managers and supervisors from the reach of NLRA rights (Lichtenstein 1998). Perhaps most prominently, the law barred closed shops (requiring employers to hire union members) and permitted states to enact their own restrictions on union or agency fee shops — provisions in collectively bargained agreements whereby unions could require workers to either join the union after starting work or to pay fees to the union to cover the costs of collective bargaining and other union services. Perversely, Taft-Hartley meant that state governments could limit union rights under the NLRA, but given the statute’s otherwise broad preemption language as interpreted by the courts, states could not pass policies expanding union rights. As we will see, labor’s opponents have taken advantage of this asymmetry to retrench the power of labor (see also Galvin and Hacker 2020).

The passage of Taft-Hartley thus foreclosed a number of union organizing strategies that would have helped the labor movement retain and gain clout against increasingly aggressive employer opposition. But it also had another pernicious consequence for the labor movement that would reverberate over the years: it meant that private-sector unions could never gain a significant presence outside of their Midwestern and Northeastern strongholds during the long New Deal era. The Congress of Industrial Organization launched its ambitious “Operation Dixie” campaign in 1946 to overcome this geographic limitation and build political and economic strength in the solidly anti-union South. But in an irony of poor timing, the CIO’s campaign began just months before anti-union capitalists and conservatives gained new tools for opposing unions with the Taft-Hartley Act. Without such support from government, the resistance from the white political and economic leadership of the South “proved overwhelming” (Lichtenstein 1989, 136).

The lost possibility of a truly national private-sector labor movement matters because of the territoriality and federalism present in American political institutions: without uniform power established across the states, the labor movement could not make a sustained bid for influence either at the state level (with control of state legislatures, courts, and governorships) or in Congress and the White House (through labor’s relationship to local and state political parties electing candidates to federal office) outside of the states in which they gained an initial industrial foothold in the New Deal. Those curbs on national power have also limited unions’ ability to pass labor law reforms that might have created new political opportunities. Quite strikingly, the only labor legislation passed since the New Deal has generally involved further restrictions on union activities — a powerful example of Congressional policy drift (explored in more detail in the Kelly and Morgan chapter of this volume; see also Galvin and Hacker 2020).

The fragmentation of the labor movement along geographic lines was joined by fragmentation along sectoral lines, as public sector workers were excluded from the rights afforded by the National Labor Relations Act. By 1935, government employees were a substantial — and growing — part of the US workforce. According to Department of Labor estimates, in the year that the NLRA passed there were just over 2.7 million state and local government employees, including over 1 million teachers and other educators, and another 820,000 federal employees. Yet as political scientist Alexis Walker (2014) has uncovered, barely any mention was made of these public employees (or their unions) in the drafting of the NLRA’s text. And perhaps even more surprisingly, the major public-sector unions at the time (including the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employee’s founding local in Wisconsin) were largely positive about the Wagner Act, encouraging their Members of Congress to support the bill in spite of the absence of any recognition of union rights for public-sector employees.

Congressional drafters of labor relations bills were well aware of the exclusion and thought that it was necessary to avoid a heated confrontation over an already-complex set of proposals. There was simply no consensus over the extension of labor rights to government employees at the time, and public-sector unions were pessimistic about their chances of gaining legal recognition even in local and state government. Indeed, among Roosevelt’s prolabor allies there was a shared sense that government employees were different from private-sector workers and the nature of their relationship to the state meant that it was not possible to collectively bargain with public-sector unions. Roosevelt himself had explained that he felt the “very nature and purposes” of government work implied that it was “impossible for administrative officials to represent fully or to bind the employer in mutual discussions with Government employee organizations” (qtd. in Cornell 1958: 48). As a result, government employee unions would need to wait for several more decades to gain the same degree of legal recognition of their rights to organize and collectively bargain — and even then, those rights would be granted at the local and state level, not from the federal government. In this way, sectoral exclusions drove further geographic fragmentation.

Strike waves pave the way for recognition of public-sector unions outside of national law

By the 1950s, many city and municipal public workers had begun forming and joining unions, even though they had no widely recognized legal protections or rights to bargain collectively with their employers (Cornell 1958). Mounting pressure led several large cities, including Philadelphia, to develop bargaining and negotiation procedures for some of these unions. In an important burst of activity in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Wisconsin passed a law recognizing bargaining rights for its municipal employees (1959), New York City established bargaining procedures for its teachers after educators, represented by the newly formed United Federation of Teachers, went on a massive day-long strike (1961), and President John F. Kennedy promulgated an Executive Order recognizing the right of federal employees to join unions of their choosing (1962).

The New York City teachers offered the playbook for how other government employees would eventually gain and expand their bargaining rights: sustained, high-profile, and very much illegal strikes (Shelton 2017). Indeed, what made public union — and especially teacher union — mobilization in the 1960s and 1970s notable was the fact that so many states and localities imposed stiff penalties on striking public-sector workers, motivated by the belief that public-sector work was not comparable to the private sector and should not be disrupted with strikes (Burns 2014). In fact, in passing initial legislation to recognize the bargaining rights of public-sector employees, many states added or bolstered bans on strikes to ensure labor peace (Anzia and Moe 2016; Paglayan 2019); in 1955, only seven states imposed legal bans on teacher strikes, but by 1975 that figure had grown to thirty-one states.2 In all, a total of nineteen of the thirty-three mandatory collective bargaining laws introduced over this period included bolstered bans on strikes (Paglayan 2019).

Thus, in order to further expand their union rights and push for higher salaries and benefits, many public-sector workers (and especially teachers) broke the law through their strikes and other collective actions. As the head of the UFT argued, even if state law said otherwise, teachers “have the right to strike [as an] ultimate weapon.”3 More recent quantitative analysis examining the passage of teacher collective bargaining rights across the states reveals the critical importance of strikes for teacher pay and classroom conditions: the expansion of collective bargaining rights only increased school spending and teacher pay — reflections of the material gains of labor’s demands where teachers possessed a credible strike threat (Paglayan 2019).

The geographic and numerical reach of these public-sector strikes, especially among teachers, cannot be overstated and headlines from the New York Times during this period offer a flavor of its massive scope: “Michigan Teacher Strikes Delay School for 500,000” (1967); “Three- Week Strike by Florida Public School Teachers Appeared at an End Today” (1968); “Teachers Vote to Strike Today: A Million Pupils Here Affected [in New York City] (1975); and “Ohio Teachers Adopt New ‘Reverse Strike’ Shock Tactic to Gain Tax Money for Schools and Substantial Raises” (1968). The country went from seeing an average of three teacher strikes per year in the 1950s to 300 teacher strikes in the 1960s, and over 100 in 1967 (Shelton 2017). At their peak, the teacher strikes involved over 324,000 educators in 1975.

It is not surprising that teachers were at the vanguard of the new public-sector activism. Teachers accounted for one of the largest occupations within the growing government employee workforce. Out of the 8.5 million public-sector workers employed in 1950, 2.3 million worked for local public schools — roughly the same number of workers as were employed by the entire federal government. Unlike other government workers who might be concentrated in a few large cities, moreover, teachers were employed in nearly every city or town, giving their movement broad and deep reach across the country. And perhaps most important, teachers held highly visible and respected roles in their communities, with social ties to students and families — ties cutting across class and party, if not race. All of those features gave teachers powerful leverage that they could use in their collective action.

Together, the large-scale collective action by teachers and other public-sector employees transformed the landscape of labor law and the labor movement more generally. While “only a small fraction of schoolteachers” had bargaining rights before 1961, by the end of the 1970s, 72 percent of all public school teachers were members of a union with legally recognized bargaining rights (Shelton 2017).

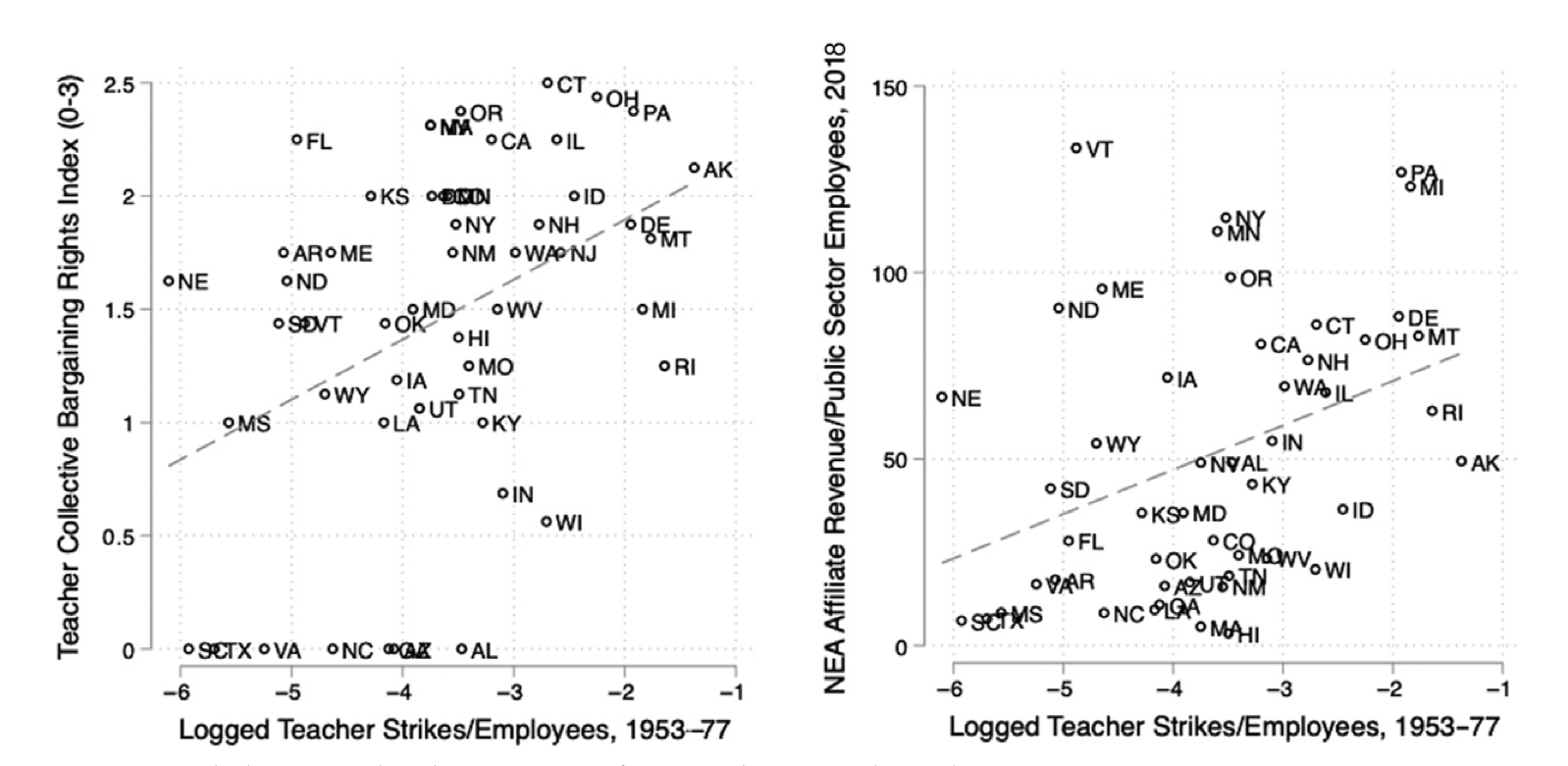

The reverberations of the massive public-sector strike waves from the 1960s and 1970s continue to present day, captured in the legislation recognizing the collective bargaining rights of teachers and, through it, in the organizational clout of public-sector labor unions (Anzia and Moe 2016; Flavin and Hartney 2015; Hartney 2014). This is a clear example of how large-scale labor collective action can feed back into public policy — with implications for political and economic organization decades later. Figure 3.4 summarizes the relationship between the historical intensity of teacher strikes in the 1960s and 1970s and present-day public policy and political resources available to teachers unions across the states.

The left-hand plot indicates the scope of collective bargaining rights enjoyed by teachers unions in 2018, averaging together a 0–3 scale for collective bargaining coverage on a variety of issues, where 0 indicates the absence of collective bargaining altogether, 1 indicates that unions are prohibited from bargaining on an issue, 2 indicates that unions and employers are permitted to negotiate over an issue but are not required to do so, and 3 indicates that the issue is mandatory for the parties to cover. As Figure 3.4 makes clear, states like Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Alaska that had greater strike activity during the critical 1960s and 1970s period continue to possess broader collective bargaining rights today. But it is not just a friendlier legal regime. Teachers unions enjoy greater organizational clout, too, as captured in the right-hand plot that examines the revenue collected by state education associations in 2018 (or the latest available year reported to the IRS), scaled by the size of a state’s public-sector workforce. States with more historical strike activity tend to have teacher unions with greater resources to invest in continued labor and political mobilization in present day (for additional quantitative analysis of this relationship, see Anzia and Moe 2016).

Figure 3.4 The long-run political consequences of 1960s and 1970s teacher strikes

Note: Teacher collective bargaining rights data from author’s review of state law. NEA revenue from IRS 990 filings. Public-sector workforce, teacher strikes, and state employment from Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Fragmentation of the public-sector labor movement — and countermobilization on the right

Returning to Figure 3.1, we can see that the rise of the public-sector labor movement occurred just as private-sector unions were steadily losing members in the face of major shifts in the economy alongside intensified employer opposition (Farber and Western 2001; Lichtenstein 2002; Logan 2006). The newly militant public-sector unions might have shored up the national labor movement as a whole. And they might have also provided a crucial linkage for the labor movement across the states, given that private-sector unions had historically struggled to connect intermediary linkages between their organization at the local, shop-floor level and at the national or international union level (Weir 2009; Hertel-Fernandez 2019b: ch. 7). By comparison, public-sector unions depended on state government for their recognition and bargaining, and therefore had good reason to establish a strong state-level presence (Skocpol et al. 2000).

Crucial to that vision of a more unified labor movement was the passage of federal legislation that would have enshrined the collective bargaining rights of public-sector employees into national law, ensuring that government workers across all states would have the same rights to form and join unions. But such a vision of unified labor was not to be. Division in the labor movement, an emboldened conservative opposition, and especially a public turn against government-sector strikes scuttled a National Public Employment Relations bill in the mid-1970s — the closest that public sector workers have come to such legislation (McCartin 2008; Walker 2014). Like the backlash against labor during the late New Deal era, the public’s growing scorn for government employee activism in the 1970s again illustrates the delicate balance workers face between engaging in disruptive activism needed to secure legislative gains while also preventing backlash when their demands are seen as illegitimate by the mass public. While earlier mobilizations by government employees were supported by broad segments of the population, the public turned against later wildcat strikes and protests seen as a power-hungry grab by government workers during hard economic times (McCartin 2008, 139). No less important, as we will see, was the growing ability of opponents of public sector unions to cast their appeals in racialized terms given the demographics of government employees and the clients they served.

As a result of the failure to expand the reach of government-sector unions, public-sector unions remained similarly geographically constrained as their private-sector counterparts. Instead of corresponding to the concentration of industrial activity across space, however, public-sector unions were concentrated in states according to the favorability of their state laws governing organizing and collective bargaining rights — which in turn reflected strike activity in the 1960s and 1970s. It is only really in the Mid-Atlantic, Northeast, and Pacific coast areas that states continue to have especially strong public-sector unions. In broad swaths of the South and West there is very minimal public union membership — a crucial element to the distinctive political economies in those “red states” documented in the chapter by Grumbach, Hacker, and Pierson in this volume.

Just as with the private-sector labor movement, then, public-sector unions’ scope to influence our highly territorialized and federalized political institutions was constrained given their geographic concentration. And even in the states in which public-sector unions retain significant membership, their integration into the broader labor movement remains highly variegated across states. While public-sector unions are working closely with private-sector unions in some states, in others they are much less coordinated with one another, especially when it comes to state politics (Hertel-Fernandez 2019b: ch. 7).

Why does public-sector union integration with the rest of the labor movement matter? To the extent that public-sector unions are not united with private-sector unions, it will be harder for the labor movement to work together and to speak with one political voice. And under those circumstances, labor unions ought to have weaker political clout in state-level politics (see also Ahlquist 2012; Hurd and Lee 2014). That is consistent with arguments advanced by Christina Kinane and Rob Mickey (2018), who make the case that union fragmentation results in reduced union political power.

Weaker incorporation of public- and private-sector unions can even lead private-sector unions to support candidates and policies that run against the interests of their government employee counterparts. For instance, in Wisconsin, the building and construction trades unions supported hard-right GOP Governor Scott Walker — even as Walker pushed for unprecedented cutbacks to public-sector bargaining rights that would devastate government employee unions, and especially those representing teachers (Kaufman 2018). In fact, several building trades unions made hefty campaign contributions to reelect Walker in 2014, well after the effects of public union retrenchment had been felt across the state.4

The bifurcation of the public- and private-sector labor movements has implications for mass political behavior, too. The demographic profile of the typical public-sector worker in the United States — and by extension, the typical public-sector union member — is very different from the private-sector workforce. Public-sector union members are much more likely to be female and to be highly educated (especially with a college degree or more) compared to private-sector workers (Wolfe and Schmitt 2018). Men represent a little over half of the private-sector workforce, but only 42 percent of state and local employee unions. Similarly, only about a third of private-sector workers hold a college degree, compared to over 62 percent of state and local union members. And while the public-sector workforce tilts whiter than the private-sector workforce, Black women in particular are over-represented in state and local government unions compared to white women and men of any race (McNicholas and Jones 2018).

These demographic differences have created potent possibilities for anti-union activists to mobilize gender, class, and racial resentment among private-sector workers against public-sector employees and their unions (Ratliff et al. 2019; Tesler 2016) and are part of the more general racialization of government and public services (e.g., Filindra and Kaplan 2020). As Katherine Cramer has documented persuasively in Wisconsin, prodded on by conservative politicians, media, and activists, private-sector workers in the state — even current and former union members — blamed government employees (and by extension, public-sector unions) for their economic woes (Cramer 2014; 2016). The main complaint of these private-sector workers was a sense that state employees were lazy, out-of-touch professional workers paid exorbitant wages and benefits from taxpayer money. In turn, public-sector largess was the reason why those private-sector workers felt they had not seen wage gains or adequate pension and health benefits (see also Kane and Newman 2019). Wisconsinites holding these feelings about teachers and other public-sector employees then became an important constituency for conservative Republican Governor Scott Walker and his campaign to retrench public-sector union rights after his successful 2010 election and part of the broader Tea Party movement (Skocpol and Williamson 2012).

As the example of the politics of resentment in Wisconsin makes clear, mass opposition to government unions has an elite basis. That elite backlash against public-sector unions, in turn, has its roots in the public-employee strike wave in the 1960s and the 1970s, which spurred an intense countermobilization of businesses and conservative activists that sought to retrench the legal rights that public-sector workers had fought to gain, including in states like Wisconsin that had long supported government employee unions (see also McCartin 2008).

Looking across the states in the 1970s, leading conservative activists were concerned about the rise of the public-sector labor movement, especially teachers, as a formidable presence in state government that were part of a broader national federation. That meant that public-sector unions, like AFSCME (representing federal, state, and local agency workers) and the AFT and NEA (representing teachers), could redistribute financial resources across their affiliates. But it also meant that they could quickly disseminate policy ideas across the states in which they had amassed substantial memberships, pushing for the same policies across many states at the same time.

Crucially, conservatives noted, public-sector unions did not restrict themselves to lobbying on issues narrowly related to their occupations, but rather were involved in a range of other policy areas (Hertel-Fernandez 2019b: ch. 7). One conservative leader noted that at the time, the “most effective lobby in the state legislatures” was the “National Education Association.” She continued:

Many people are deceived by believing that the National Education Association lobbies only for education-related legislation, but they don’t. They oppose right to work laws, they oppose balanced budget resolutions, they support comparable work bills, they get involved in just about every piece of major legislation in the state legislature. They are very well organized, extremely well-funded. (qtd. in Hertel-Fernandez 2019b: ch. 1)

Summing up, another conservative leader explained that groups like the newly enlarged teachers unions

came up with model legislation, which [they] would push in several states at the same time … [and then they] would use the argument, “Well, if so-and-so passed it, it must be okay.” And so the bill would go forward, sometimes in 30 states and more. Usually, the liberal bill moved from committee to floor vote before you [the conservative activists] got prepared and marshaled your arguments, if then. The local [conservative activists] were on their own in each state — and they were overwhelmed. (qtd. in Hertel-Fernandez 2019b: ch. 1)

In response, a small group of right-leaning politicians, aided by several conservative institution-builders and donors, formed the “Conservative Caucus of State Legislators,” intended to provide a forum and support network for state elected officials who wanted to promote a more conservative agenda. Later rebranded as the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), this organization would go on to bring together private-sector businesses, conservative activists and donors, and state legislators to craft “model bill” proposals for state governments.

While the issues that ALEC has pursued have changed over time, reflecting the changing composition of its membership, one common through line across its history of bill proposals has been the promotion of bills attacking labor unions above all unions in the public sector. These include proposals for right-to-work laws banning agency fees, cutbacks to collective bargaining rights, measures to make it more challenging for unions to collect dues, obstacles to union political mobilization, and onerous requirements for regular recertification.

ALEC has never seen these anti-labor bills as ends in themselves. Rather, ALEC has helped its members, especially its corporate members, to understand that passing bills cutting back public union labor rights would weaken liberal political power and make it harder for Democrats to win elections. That, in turn, would pave the way for ALEC to pass legislation favored by its private-sector businesses, libertarian activists, and social conservative advocacy groups.

ALEC’s pitch about retrenching public-sector union rights was innovative because there is no reason why all of its members, especially many of its corporate members, would necessarily be invested in battling teachers or other government employees. While school choice reformers and other small-government libertarians had a clear reason to go up against teachers, ALEC’s private-sector businesses did not have a direct motive to get behind the drive as opposed to ALEC’s other efforts related to tax cuts, regulatory rollbacks, or business-friendly subsidies. Instead, it was a testament to ALEC’s coordination as an association that it helped its corporate constituents see the value of using policy not just as a means of achieving specific technical objectives (like promoting school choice or pursuing tax cuts) but rather a way to reshape political power — by defanging their opponents (Feigenbaum et al. 2019; Hertel-Fernandez 2019a). Here we can clearly see the crucial role of business associations (led by political activists and entrepreneurs) in promoting collective action of firms against public unions in contrast to unions in the private sector (see also Martin 2000; Martin and Swank 2012). In this way, ALEC’s conservative leaders helped to steer private-sector firms toward the conservative, anti-government agendas documented both in the Introduction and in the chapter by Rahman and Thelen in this volume.

Over time, ALEC’s efforts were buttressed by two other cross-state networks also focused on defeating the labor movement: the State Policy Network (SPN; founded in 1986) and Americans for Prosperity (AFP; launched in 2004). While the SPN focused on assembling a network of conservative, business friendly think tanks in each state, AFP built a federated advocacy group of grassroots volunteers and paid staff that could intervene in school board, city council, state, and federal elections and policy debates. But despite representing different constituencies and engaging in different activities, all three organizations promote similar policy priorities, especially when it comes to defeating public-sector labor unions.

These three organizations have championed a number of state-level cutbacks in union rights that have weakened unions and Democratic electoral odds in states like Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, Kentucky, and West Virginia (Feigenbaum et al. 2019). But importantly, the three conservative networks have not restricted themselves to fighting in the state legislative arena. They have also sought measures to stymie government employee unions through the courts, and SPN think tank affiliates have supported several of the recent federal court decisions that make it harder for public-sector unions to attract and retain members and raise revenue (Hertel-Fernandez 2019b: ch. 7; see also Rahman and Thelen’s chapter in this volume).

Most significantly, SPN affiliates helped to provide the intellectual case for the Janus v. AFSCME decision (and its precursor in Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association), which ruled that no public-sector union can charge fees to non-members, even if the non-members benefit from union-bargained contracts and grievance procedures. That decision effectively applied right-to-work to all government employees, even in previously non-right-to-work states, like New York, California, and Illinois, greatly hindering the ability of public-sector unions to attract members and sustain revenue. The courts thus helped conservative activists to achieve retrenchment of public-sector union power even in states where those activists could not have hoped to pass new state legislation. In a good illustration of how American political institutions favor organized groups that can move seamlessly between venues, as soon as the decision passed, SPN affiliates worked with AFP’s grassroots chapters to contact government employee union members and inform them of their newly gained rights to leave their union without having to pay agency fees, further weakening labor power.

In sum, the wave of public-sector strikes that rolled across the country throughout the 1960s and 1970s deeply reshaped American political terrain. Through these strikes, government employees convinced the public — and ultimately elected officials — of the worthiness of their demands for higher wages, benefits, and collective bargaining. Where public-sector workers organized and engaged in more extensive labor action, they were more likely to see state laws entrench their rights to form unions, collectively bargain, and collect dues. And through those laws, unions were able to organize more members and raise more revenue. Yet the strike wave was incomplete, missing many parts of the country that would never expand bargaining rights or did so only partially, leaving public-sector unions fragmented geographically and sectorally within states. The strike wave also prompted an extensive countermobilization from the right that would come to represent one of the most significant threats to the labor movement in recent decades.

Beyond these obstacles to a truly national public-sector labor movement, there are other reasons to be skeptical of further large-scale government union expansion in the United States. The growth of the public-sector workforce has slowed considerably since the 2000s, limiting the pool of potentially eligible workers to join government employee unions. More generally, there remains deep skepticism among many politicians about increasing the size of the public sector, even on the left (Hacker and Pierson 2016). In recent decades, Democrats, fearful of provoking backlash, have instead relied on subsidized or regulated private alternatives to expand public programs (Howard 1997; Mettler 2011). Not only do such “submerged” or “hidden” policies limit the direct employment of government workers, but they also obscure the role of the state, making it harder to build support for expansions of public authority in the future (Mettler 2011). While some Democrats have moved away from this more modest vision of government — for instance, with proposals for the Green New Deal or Medicare for All as well as the emergency relief program enacted by President Joseph R. Biden in early 2021 — plans to durably expand the size of the state face long odds even with full Democratic control of the White House and Congress.

Instead, future public-sector union activism seems most likely to be successful around policies that raise labor standards but do not necessarily increase the size of government, and focused on states that have been cutting essential public services to the point where even conservative citizens are willing to support boosts in public spending. We now turn to two examples of these campaigns in the “Fight for Fifteen” and the “Red for Ed” movements.

The new labor law to the rescue?

Assessing recent developments in labor politics, Kate Andrias (2016) has argued that we are seeing the emergence of a “new labor law” that views unions as political actors and seeks to raise working standards across entire sectors and regions, rather than simply at the level of the individual firm. Chief among these examples of new organizing is the Fight for Fifteen movement. Launched in 2012 among low-wage service and retail workers, the campaign is calling for employers and local, state, and federal officials to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour and to recognize workers’ right to form a union.

Although the movement did not directly involve public-sector employees, there are strong parallels between these protests and the strike waves of the 1960s and 1970s in that both the low-wage workers in recent years and the public-sector workers in earlier decades were seeking to raise their labor standards through state legislation. Moreover, both sets of labor actions were conducted outside of traditional labor law: for the low-wage service workers because they lacked a union and for the public-sector employees because they either did not yet have formal bargaining rights or lacked strike rights. And lastly, the biggest backer of the Fight for Fifteen movement is the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), which is by now the second-largest public-sector union in the country, representing more than a million local and state government workers, public school employees, bus drivers, and childcare providers.5

Initially, the Fight for Fifteen movement took the form of walk-outs and strikes among fast-food workers at large chains (like McDonalds, Burger King, KFC, and Papa John), but eventually the protests expanded beyond the restaurant sector to include low-wage workers in other industries, culminating in wide-spread demonstrations in some 340 cities. As the direct action continued, community advocacy groups began pushing for legislative and ballot initiatives to raise minimum wages and create other labor market standards — like paid sick and family leave — in a number of cities and states across the country. The campaign boasts that some 10 million workers are on track to receive a $15 an hour minimum wage, and that 19 million workers have received minimum wage boosts since the movement launched (figures from Ashby 2017). And in major symbolic victories, the Democratic Party adopted the target of a $15 an hour minimum wage in its official platform going into the 2016 election and plans for a federal wage hike to that level were initially included in President Biden’s rescue plan in 2021.

These are enormous gains that have directly improved the lives of millions of low-wage American workers and undoubtedly shifted the consensus around labor market standards within the Democratic Party (Greenhouse 2016). But without changing the distribution of political power at the state level, the Fight for Fifteen movement cannot truly reach across the whole country, especially in states controlled by Republicans given the federated structure of American government. Republican-controlled states can simply pass “preemption” laws that squelch the ability of their cities to enact labor market standards exceeding the state level (Hertel-Fernandez 2019b: ch. 7). That means that a city in a preempted state cannot increase its minimum wage beyond the level set by the state’s legislature. And that is exactly what Republican governments have done, aided by the conservative cross-state networks I described earlier, above all ALEC. By 2016, nearly six of ten Americans lived in a state that preempted local minimum wage increases and nearly four of ten lived in a state preempting local paid sick or family leave. (Hertel-Fernandez 2019b: ch. 7; Bottari and Fischer 2013). Thus, the full impact of the Fight for Fifteen movement will only be felt in states where Democrats and progressives already had a substantial degree of political power. The Fight for Fifteen has no purchase in red state economies.

Beyond the limits of its geographic reach, the Fight for Fifteen movement also faces challenges of sustainability. The initiative was originally launched by the Service Employees International Union in an effort to seed a bold “game changer” that could generate the same sort of energy as the vibrant 1930s organizing efforts of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (Ashby 2017; Rolf 2016). But while the effort undoubtedly met its first goal of changing the national discourse around low-wage work, it fell short on its second goal to organize low-wage workers participating in the campaign into “durable worker organizations” that could “build working-class power” (Rosenblum 2017). And without generating substantial numbers of new, dues-paying union members, it is unclear how much Fight for Fifteen contributes to the organizational strength and long-run revival of the labor movement. In part as a result of these difficult considerations, SEIU looked to be winding down its direct commitment to the movement in 2018 (Jamieson 2018).

If the Fight for Fifteen campaign is to have lasting consequences beyond the minimum wage laws it has succeeded in passing outside of red states, it will likely be through the activists and leaders it has helped to train and by the shifts in public opinion it has led. The question is whether future labor efforts can successfully mobilize those grassroots leaders and the mass public to change legislation in ways that would facilitate greater unionization of the low-wage workforce that Fight for Fifteen failed to accomplish. What made the 1960s and 1970s public strike waves so effective was the way that government workers channeled their energy and mass support into changing laws that not only raised wage and benefit standards for their particular occupations but that also bolstered their collective rights to organize and bargain, thereby helping to generate policy feedback effects that empowered public-sector labor unions for decades to come.

A very similar question hangs over the recent teacher strikes, also dubbed the “Red for Ed” movement. In February 2018, a group of activist West Virginian teachers convinced their state’s teachers unions to go on strike in response to complaints about persistently low wages and the mounting cost of their health insurance plans (Hampson 2019; Hauser 2018). The strike took many by surprise, especially since it unfolded in a very conservative state with weak public-sector labor unions where teacher strikes are illegal. Even more surprising was the response of the state government: after a two week-long strike that left more than 250,000 children out of school and included marches on the state capitol, the legislature promised teachers and other school employees a 5 percent raise and the creation of a task force to address the issue of health insurance costs (Bidgood 2018).

Inspired by the West Virginia teacher’s mobilization — and success — similar walkouts and strikes spread to Oklahoma, Kentucky, Colorado, Arizona, and North Carolina. In all, the strikes included over 350,000 teachers and millions of students, and achieved gains in many of the states. Oklahoma secured salary raises for teachers and support staff, plus a boost in public school funding; Colorado gained a salary increase and a restoration of pre-recession education spending; and Arizona obtained big increases in teacher and staff salaries.

Like the Fight for Fifteen, the 2018 teacher strikes bear a strong resemblance to the “New Labor Law” Andrias describes, as well as the older wave of teachers strikes in the 1960s and 1970s. Like the older teacher strikes, workers were engaging in labor actions outside of traditional labor law (often illegally) in order to raise working standards for an entire sector through the state legislative process rather than through traditional collective bargaining with individual employers or school districts. State governments in these red states were acting like the high turnover, monopsonistic employers documented in the Naidu chapter, this volume, using their labor market power to suppress teacher pay. And much like the Fight for Fifteen movement, the 2018 teacher strikes have secured important wage and benefit gains that were previously unthinkable before large-scale collective action.

But the Fight for Fifteen movement also shares another similarity with the 2018 teacher strikes that conveys the limits of both approaches and sets them apart from the 1960s and 1970s public-sector strike waves: in neither case did the movements secure changes in policy that would grant greater institutional and organizational rights for the workers in the form of new union representation, expanded collective bargaining rights, or strike rights. As a result, it is an open question whether the teacher mobilizations from 2018 can have the same entrenching effects that the 1960s and 1970s teacher strikes did in establishing the enduring organizational and political clout of teachers unions and remaking the map of state union power.

Instead, like Fight for Fifteen, the most significant consequences of the teacher strikes may be their effects on public opinion, as they persuade members of the public of the worthiness of teachers’ demands for higher working standards and also provide lessons to others (including teachers, but also workers in other occupations) about what labor collective action can accomplish (Biggs 2005; Soule 1997; Wang and Soule 2012). Qualitatively, there is good reason to think that the teacher strikes have had such effects, as the leaders in later states cited the earlier strikes (and especially the West Virginian strikes) as inspiring them to take action. One of the activists in Arizona who spearheaded that state’s strikes said that he believed West Virginia’s strike was “inspirational” for Arizona teachers, and that it “woke up a sleeping giant” in classrooms across the country (Arria 2018). Polling I have conducted with Suresh Naidu and Adam Reich backs up the intuition that the 2018 teacher strikes changed how the public thinks about teacher collective action — and about the labor movement more generally (Hertel-Fernandez, Naidu, and Reich forthcoming).

Looking forward then, the 2018 strikes may have not only contributed to a reservoir of public support for legal change and greater labor organization, but also helped to develop a smaller cadre of labor activists who may go on to participate in the costly work of future labor organizing and action (Uetricht and Eidlin 2019). There is early evidence for that theory in how teachers have used the structures and networks constructed during the 2018–19 mass mobilizations to protest unsafe school reopening plans during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It will be up to labor union leaders to take advantage of that supportive public climate and “militant minority” within their ranks in the months and years to come. To the extent that labor unrest in the public sector continues, these conclusions suggest that government employee mobilization is likely to be most successful at making new gains in state revenue and spending, as well as in building union strength, in contexts where politicians have been starving communities of highly valued public services — likely to be made all the more acute given cuts to state and local spending forced by the pandemic downturn. Under those conditions, even conservative voters can be persuaded of the worthiness of public employees’ demands for greater resources for important government spending. Those include many states under full or partial Republican control, but also Democratic states like Colorado or California, that have imposed sharp limits on the revenue they can raise on public services like education.

Lessons for understanding the US labor movement and the American political economy

In this chapter, I have sketched out how a political economy perspective on the development of the American labor movement illuminates important themes that might not otherwise emerge with a conventional treatment of unions. Beyond inviting further comparative research on the interaction between public and private-sector labor unions, this chapter also carries several broader insights about the American political economy, relating to geographic and territorial fragmentation, distinctive alliances between private-sector businesses and right-wing political activists and donors, and the role of the law and courts.

Geographic Fragmentation in American Politics. In our Introduction for this volume, we underscored the unique power that states have in the American federal system, and that means actors organized at the state level in multiple states can exercise considerable influence over policy-making within states (through state legislatures and governors) and at the national level (through the territorially represented Congress and Electoral College). This cross-state clout — or the lack thereof — forms a critical part of the explanation for the relative political weakness of the American labor movement, as well as its brief moments of strength. As the brief comparative analysis illustrated, the decentralization and unevenness of public-sector labor policy is also one of the most unique aspects of the American labor-policy regime looking at other rich democracies. The decentralization of public-sector labor policy also affords disproportionate influence to the business and conservative political coalitions that have emerged in recent decades to challenge union power. This is because decentralization grants businesses greater structural influence over policy-making (Culpepper and Reinke 2014; Hacker and Pierson 2002) and because weakly professionalized state legislatures are more dependent on outside interest groups for legislatives resources and ideas (cf. Hertel-Fernandez 2019a).

Business Alliances against Public-Sector Labor. Large segments of American business have long opposed the expansion of private-sector union power — both on the shop floor and in government (Lichtenstein 2002; cf. Swenson 2002). That is also true of labor unions in other countries (e.g., Korpi 1983). More unusual is the fierce resistance of American firms to government employee unions since the 1970s. Their opposition to public-sector unions is puzzling given that public-sector unions do not directly threaten the prerogatives of most private-sector managers. Why are these businesses committing economic and political resources to weakening the clout of public-sector unions? The answer lies with coalitions of conservative activists, politicians, and donors that successfully convinced corporate executives of the political dividends available from defeating public-sector unions. This reflects a more general long-term alliance between American businesses and conservative politics, alluded to in our Introduction, which has had profound implications for a variety of policy debates, including labor politics. Aligned with conservative movement groups, US businesses have adopted increasingly far-right positions out of step with historical positions and indeed with positions of their counterparts in other countries (e.g., Hacker and Pierson 2016; Martin and Swank 2012). Although this alliance has elite roots, it has also found mass support. Conservative political leaders have tied racial grievances among white voters to resentment of government — and of government employees and their unions. It was possible for entrepreneurial conservative leaders to make this connection using existing racial stereotypes and the overrepresentation of minority Americans, especially Black Americans, in public-sector jobs. This potent combination reflects a more general fusion of ethnonational appeals together with elite business and donor economic interests in the contemporary Republican party (Introduction, this volume; Hacker and Pierson 2020).

The Role of the Law in Constructing the US Political Economy. This chapter lastly joins a long line of scholars in underscoring the importance of the law as an explanation for the development of the American labor movement in mediating political and economic power (e.g., Forbath 1991; Hattam 1993; Orren 1991). But rather than simply reiterating that the law, and its interpretation by an employer-friendly judiciary, structures the opportunities available for unions, this chapter focuses attention on the feedback loops present between collective action and policy. As the enduring example of the 1960s and 1970s strike wave illustrates so vividly, mass labor collective action can change the law, entrenching new rights and resources for workers and therefore strengthening the political position of their unions for years to come. But the reverse is also true: as conservative opponents to unions have long recognized, cutbacks to union rights yield mounting political dividends. If unions are to reverse their decades-long decline, let alone make new gains, they would be wise to draw on large-scale collective action that can imbed new rights into American law once again.

Footnotes:

1 J. Visser, ICTWSS Database, version 6.1. Amsterdam: Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies (AIAS), University of Amsterdam. November 2019.

2 National Bureau of Economic Research Public Sector Collective Bargaining Law Data Set, with updates from Kim Rueben and Leslie Finger.

3 “Teachers Group Firm on Strikes.” 1961. New York Times: November 27.

4 See www.wisdc.org/news/press-releases/76-press-release-2015/4888-unions-contributed-more-than-83k-to-help-reelect-walker.

5 www.seiu.org/cards/these-fast-facts-will-tell-you-how-were-organized/.