In this research spotlight, a study by Florencia Torche and Alejandra Abufhele examines whether the benefits of parents’ marital status for children depend on the social context.

Children born to married parents have been shown to fare better — in terms of their health, education, and even their economic wellbeing as adults — than the children of unmarried parents. This advantage, known as the marriage premium, is often considered to result from two separate factors: the selectivity of parents who marry, and a benefit that derives directly from marriage itself.

But how much of this premium results from how marriage, as an institution, is perceived and evaluated within a society? And if this evaluation changes, and marriage is no longer normative, does the marriage premium disappear?

A paper by Florencia Torche of Stanford University, who is a Stone Center Affiliated Scholar, and Alejandra Abufhele of Universidad Católica de Chile, analyzes whether the marriage premium is contextual: an effect of the normativity of marriage within a society. They examine the case of Chile, where the percentage of children born to married parents has fallen sharply and quickly: from 66 percent of all births in 1990 to 27 percent in 2016. Their study focused on children’s health at birth, as measured by birth weight, gestational age, and fetal growth. “We focus on birth outcomes because they are the earliest indicators of child’s health and wellbeing that can be observed, and because they predict health, cognitive, educational, and socioeconomic outcomes over the life course, potentially shaping trajectories of disadvantage,” the researchers write.

Many studies have shown a link between the marital status of mothers and infant health. But determining the source of this benefit requires looking beyond individual factors — such as a mother’s mental health, behavior, and the emotional and financial support she receives from her spouse — to societal factors, the researchers argue. “We hypothesize that the benefits of marriage for children emerge at least partially from the status of marital fertility as a normative institution — a socially shared pattern of behavior that includes a prescriptive component about what people should do enforced by informal rules,” the researchers write.

The percentage of births that occur within marriage has declined since the 1950s, beginning in Northern Europe. During the period the researchers studied — 1990 to 2016 — this percentage fell in countries across Europe and the Americas, reflecting an increasing acceptance of family households and partnerships that don’t involve marriage. Chile, which currently has one of the lowest rates of marital fertility in the world, has experienced sweeping cultural changes in recent decades. In addition to an increasing acceptance of nonmarital cohabitation, a national legal reform in 1998 abolished discrimination against children based on the marital status of their parents.

One indication that the perception of marriage has changed within Chile is that the percentage of births outside of marriage has increased within all socioeconomic groups and equally among cohabiting and single mothers, the study shows. In fact, the increase was greatest among highly educated women. The percentage of births outside of marriage rose to 82.5 percent in 2016 from 42.2 percent in 1990 among women with a primary level of education. This percentage rose to 61.5 percent from 14.6 percent, a more than four-fold increase in 16 years, among women with post-secondary education.

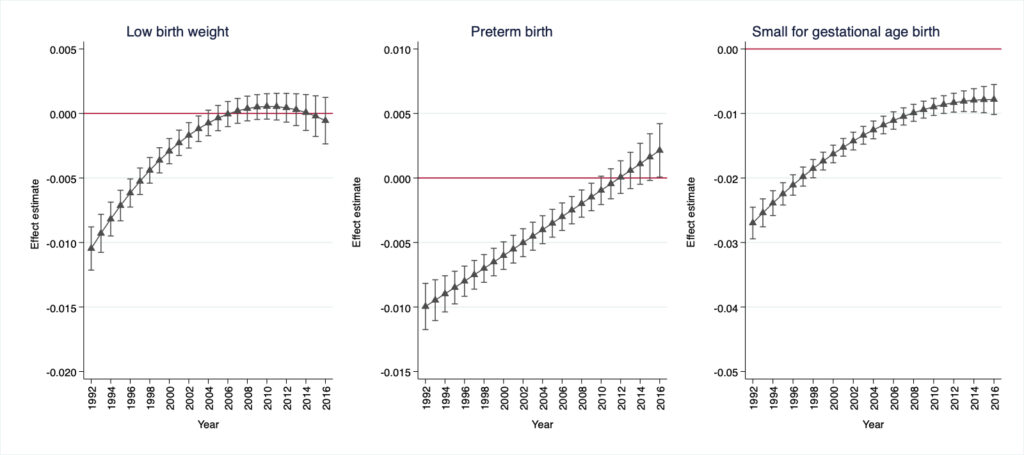

In this changing societal context, how did the value of the marriage premium change? In the early 1990s, there was a significant advantage associated with marriage for the factors of low birth weight, preterm birth, and small-for-gestational-age at birth, the researchers found. However, by the mid-2010s, this advantage was negligible in the case of low birth weight, had completely disappeared for preterm birth, and had declined by about two-thirds for small-for-gestational-age at birth.

Figure 1. Fixed effects estimates of marriage premium for (a) low-weight birth, (b) preterm birth, and (c) small for gestational age birth in Chile 1992–2016. Filled circles are parameter estimates, vertical lines are 95% confidence intervals, red horizontal line identifies no marriage premium. Based on sample of matched children of the same mother (sibling sample). In addition to mother’s fixed effects, models account for mother’s age, mother’s education, parity, sex, urban residence, region of residence, and year of birth.

Socio-demographic differences between married and unmarried mothers account for a portion of the marriage premium for birth outcomes, the researchers found. However, the impact of these differences did not change from 1990 to 2016, and controlling for these differences also shows a clear indication of a declining marriage premium.

These findings support the argument that the marriage premium declines as marital births become less normative. “Given that the normativity of marital fertility has declined over time in much of the world and will likely continue to do so, the advantages of marriage for children, net of the characteristics of married parents, could whither or fully disappear over time in many societies,” the researchers conclude. “This finding, as intuitive for sociologists as it might be, has consistently been neglected both by empirical analyses about the consequences of nonmarital fertility and by policy debates about how to address it.”

The Normativity of Marriage and the Marriage Premium for Children’s Outcomes”