Aman Desai, a Ph.D. candidate in economics at the Graduate Center and a Stone Center Junior Scholar, is the author of “Measuring Income Inequality of Opportunity,” a working paper recently added to the Stone Center Working Paper Series. In this interview, Desai discusses his findings, his experience working with his advisor and Stone Center Senior Scholar Miles Corak, and how his interest in engineering and mathematics led him to inequality studies.

What is the main finding of your paper?

Desai: I’m interested in inequality of opportunity and human capital development in childhood. I focus on childhood circumstances and the inequalities that they generate. This paper is about measurement of inequality of opportunity. I argue that some inequalities are fair and some are unfair. But which inequalities are fair and which are unfair? That’s a normative question, an ethical question. People have different views about it.

There is an idea, based on work by John Roemer at Yale University, that inequalities that are generated from circumstances beyond your control are considered unfair. We call that inequality of opportunity. But what are those circumstances? Some circumstances are easy to agree on, such as race and gender, since those are beyond an individual’s control. But let us take educational attainment. Some researchers argue that it is an effort variable, given that educational attainment is in an individual’s control, while others might argue that it is a circumstance, given that, for example, an individual may have been born into a culture where traditional education is emphasized. So, the categorization of circumstances while measuring the inequality of opportunity is based on the value judgements of the researcher.

What I say is: instead of doing that, why not just use age? If you’re not an adult, you shouldn’t be held responsible for what’s going on around you. I use age as a boundary between circumstances and efforts, between things you can’t control and things you can control. Society determines when a child is considered an adult. Maybe in the U.S., that age is 18, maybe in France it’s 16 — but whatever age we use, it’s not based on my (the researcher’s) value judgment. I’m removing the idea of solving this problem of ethical differences.

Then what I do is I bring in an insight from human capital development in early childhood from James Heckman at the University of Chicago: the idea of dynamic complementarity. Children are like sponges during their early years. It’s easy for them to learn things when they’re young, compared to when they’re old. Research shows that in the U.S., by the age three, children born in rich households have a 50 percent larger vocabulary than children who were born in poor households. Skills gaps that emerge early in childhood tend to persist into adulthood. Therefore, I contend that to measure inequality of opportunity rigorously, we should account for how childhood disadvantages compound over time.

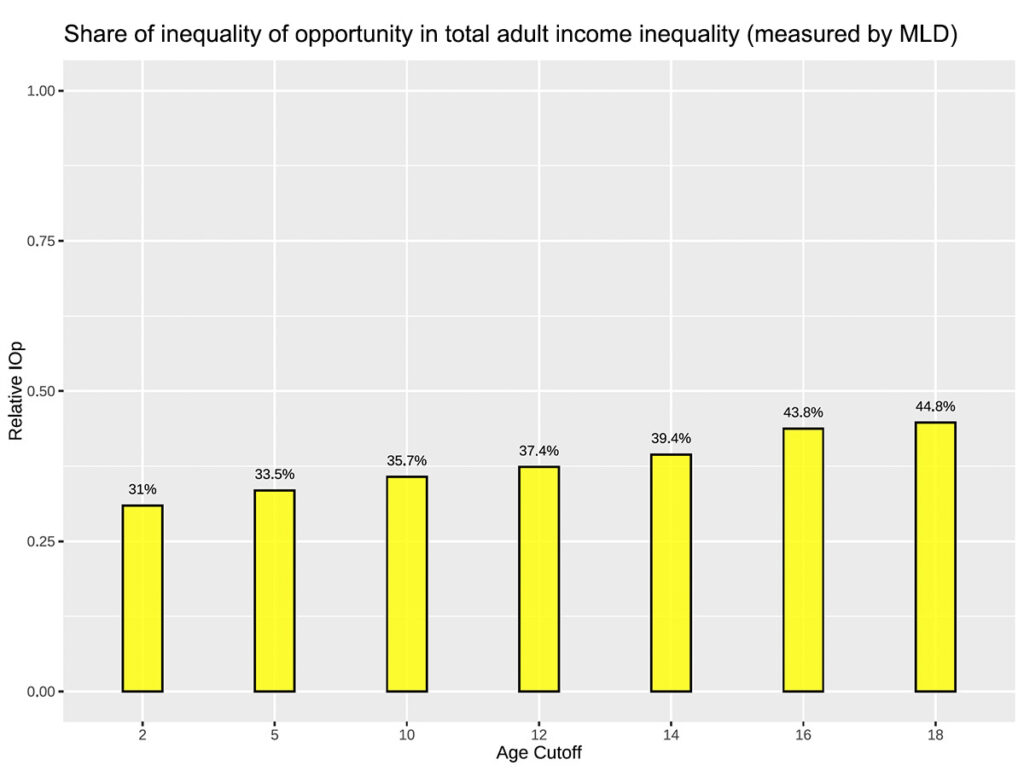

Using this approach, I create four sets of circumstances, corresponding to key childhood stages, and measure inequality of opportunity at ages 2, 5, 14, and 18. Using a random forest — a supervised machine learning algorithm — I generate a counterfactual distribution of adult incomes based solely on these circumstances. I then calculate inequality of opportunity using a standard measure called mean logarithmic deviation. The results show that over 40 percent of total inequality in adult incomes can be attributed to inequality of opportunity. More significantly, more than one-third of total income inequality stems from circumstances before a child enters K-12 (before age 5). Whether one supports later-life compensation for missed opportunities or advocates for equalizing opportunities through early childhood investment, the key point remains: when measuring inequality of opportunity, we must account for how the effect of unequal circumstances in childhood compound over time.

Does the use of age as a boundary mean that race, gender, the educational background of a child’s parents, parental income, or other factors don’t need to be considered in inequality of opportunity research?

Desai: I’m not trying to replace or exclude those other factors, but my framework shifts the emphasis to the age dimension. For instance, if we consider parental income, it will be measured at one point in time or usually averaged over some years. What I’m saying is that it matters when the parental income is measured. Maybe a child’s parents are rich or well-off later in their childhood, but during their early years, the parents were struggling — that is important.

I do include race, gender, and other such circumstances, because these are factors people cannot control. There are many variables beyond a child’s control — whether their family has housing, medical insurance, transportation, or even the ability to put food on the table — that I also include.

How did you select the age of majority at 18 as a boundary?

Desai: For the U.S., I start with the age of majority at 18. Drawing on the insight of dynamic complementarity, I create four circumstance sets based on critical stages in childhood and measure inequality of opportunity using circumstances measured up to each of these stages at age 2, 5, 14, and 18 years. As you see on the graph [below], the shares of inequality of opportunity in adult income inequality are reported.

You see about 34 percent of income inequality — measured using mean logarithmic deviation — comes from unequal circumstances up to age 5. I consider many variables that might influence children in their formative years that are informed by literature on human capital development in childhood, including gender, race, and parental income, and whether their family has housing, medical insurance, and other circumstances, which I can see from the PSID [Panel Study of Income Dynamics] data. These data are measured across the first 18 years of a child’s life, depending on their availability in the PSID. My outcome variable is the child’s age-adjusted adult individual income measured from around age 33 to 37, averaged across four years, from the PSID.

Now, people may not be fully convinced about the responsibility boundary at age 18 and its relationship to circumstances, and I understand that. But the point here is that while measuring inequality of opportunity via the role of circumstances, we should consider that opportunities or lack thereof in childhood can have persistent impact in adult outcomes. If you look at the results, over one-third of adult income inequality could be attributed to unequal circumstances before or at age 5. So, even though people may disagree on the age of majority at 18, it is impossible to overlook the inequality of opportunity early in childhood. It is difficult to argue that a 5-year-old has control over her life.

How did you become interested in studying inequality?

Desai: In my first year, I was a research assistant to Professor Corak as part of a Graduate Center fellowship. He gave me a book by Robert H. Frank titled Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy and asked me to replicate its graphs using simulations in R. I reverse engineered many graphs and results in the book, which first exposed me to inequality and how to think about these concepts, particularly the departure from traditional competitive markets and the existence of winner-take-all markets.

Additionally, when John Roemer visited the Graduate Center to present his work, I found a new direction. His book Equality of Opportunity gave me deep insights into the concepts of “fair” and “unfair” components of inequality. This inspired me to pursue research in the field.

Before coming to the Graduate Center, you earned an MS in econometrics and quantitative economics from the University at Buffalo, SUNY, and a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering from Gujarat Technological University in India. What made you decide to switch from engineering to economics?

Desai: I’m really into culture, politics, history, and economics — those are four things I really love to read about. I realized this when I was in my second or third year in civil engineering, and then I decided I wanted to study economics, but I had to finish engineering because we didn’t have the major/minor system in the institution I attended.

I was attracted to economics because it allowed me to apply mathematics to social science, combining my engineering training with my passion for understanding society. There are similarities in the way mathematical and systems thinking is applied in engineering and economics. Although, this thinking is way more difficult in economics, because economic systems involve humans and not machines.

Read the Study: