January 4, 2023

In this post, the Stone Center’s Janet Gornick and Branko Milanovic assess what underlies the high level of income inequality in the U.S. They discuss the results of their study, “In Search of the Roots of American Inequality Exceptionalism: An Analysis Based on Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Data,” conducted with Graduate Center Ph.D. student Nathaniel Johnson and published as the lead chapter in Measuring Distribution and Mobility of Income and Wealth. This recently published volume is part of NBER’s Studies in Income and Wealth (University of Chicago Press).

By Janet Gornick and Branko Milanovic

What are the reasons for the well-known high inequality in the U.S., in comparison to other rich countries? In our study, we focus on the demographic decomposition of inequality, disaggregating populations in a way that has not been done before. Our variable of interest is inequality based on households’ market income, which, in practice, means income from the labor market that is brought home by all of the members of a household. From this point forward, we refer to this labor income as “household earnings” or simply “earnings.”

We began with the knowledge that U.S. earnings inequality, across households, is high compared to other affluent countries. We selected a set of 24 countries (see Endnote) — for which we had access to microdata at around 2010 from the LIS Database — and started with three intertwined questions:

* Is the comparatively high level of earnings inequality in the U.S. caused by unusually high inequality within one or more demographic subgroups in the U.S. population? This is often referred to as “within-group inequality.”

* Is it high because one or more of these U.S. subgroups has exceptionally high, or exceptionally low, average earnings? This is often referred to as “between-group inequality.”

* Is it high because one or more exceptional subgroups are more or less prevalent in the U.S. than elsewhere?

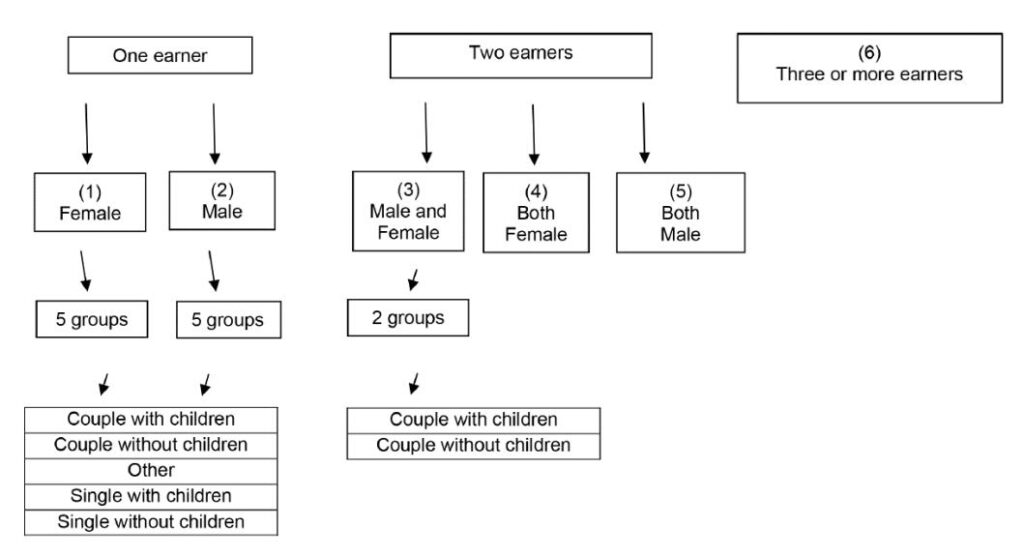

We divided each country’s working-age population into six household types, based on the number and gender of its earners. Our six main subgroups are households that contain: 1) one female earner, 2) one male earner, 3) one male and one female earner, 4) two female earners, 5) two male earners, and 6) three or more earners. After analyzing these six subgroups, we disaggregated the first three even further, based on households’ partnership and parenting status. The final design, reported in Figure 1, included 15 subgroups.

Figure 1. Typology of households based on number and gender of earners, further disaggregated by partnerships and parenting status

Notes: The six main types of households are indicated by numbers 1–6.

Below, we summarize our findings:

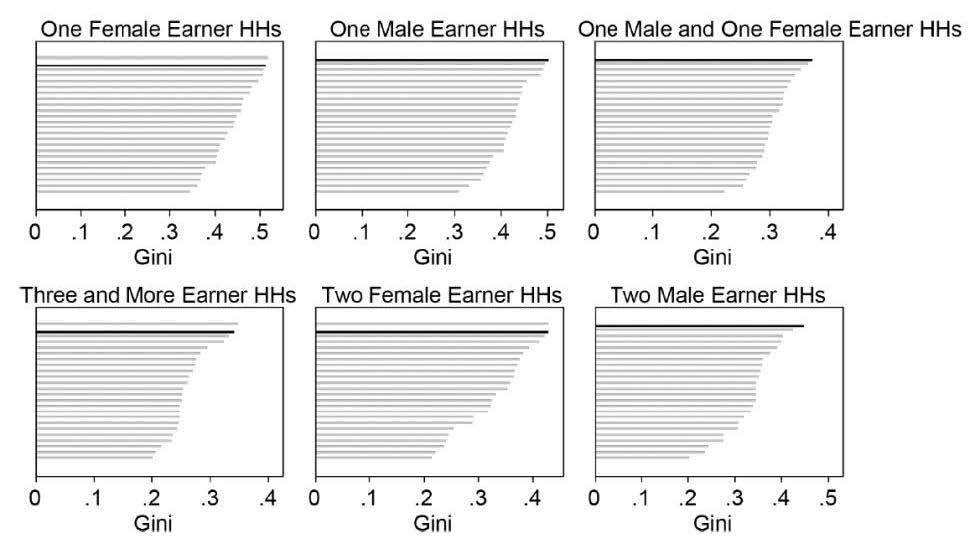

The answer to our first question is, yes, “within-group inequality” in the U.S. is consistently high across our subgroups. In this particular way, the household earnings distribution in the U.S. might be described as “equally unequal.” Figure 2 presents earnings inequality across countries, with inequality captured by the Gini index, where a higher value signifies greater inequality. The position of the U.S. Gini (highlighted in black), is compared to the other 23 countries, for each of our six main subgroups. For three subgroups (one male earner, one male and one female earner, and two male earners), the U.S. has the most unequal distribution of all countries; for the other three household types, the U.S. distribution is the second most unequal. In no case is the U.S. Gini even close to the median Gini for a given household type, much less lower than it. Although we don’t show it here, this result carries though when we look at the 15 more finely disaggregated subgroups: U.S. inequality is high within all of them.

Figure 2. Inequality in six main household types

Notes: Each bar shows the Gini of a given subgroup and country. The U.S. Gini is highlighted in black. Ginis are ordered from the highest to the lowest.

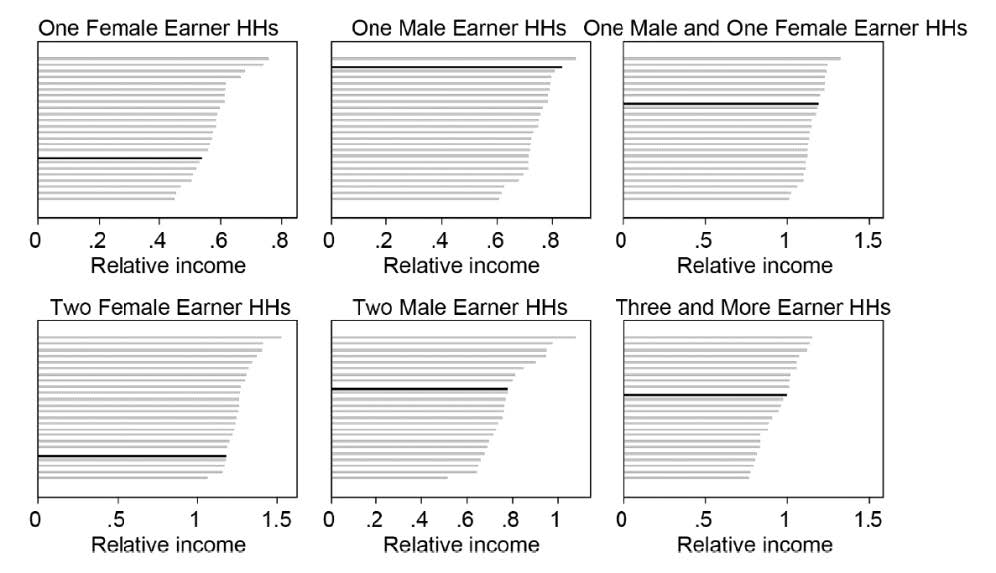

The answer to our second question is largely no; we found little evidence that “between-group inequality” drives the high overall level of inequality that characterizes the U.S. Figure 3 is constructed similarly to Figure 2, but here we report relative labor income levels across the six household types. Labor income levels are expressed as the mean household earnings of that subgroup, compared to mean household earnings overall in the same country. Here we see that the U.S. position, with the exception of two-female-earner households (relatively low) and the one-male-earner households (relatively high) is not exceptional. (Again, although we don’t show it here, this result holds when we consider the 15 more finely disaggregated subgroups.) This, in turn, implies that the origin of high labor income inequality in the U.S. is not to be found in unusually high earnings of some subgroups, or unusually low earnings of others, but in consistently high earnings inequality within each household type.

Figure 3. Relative labor income of six main household types

Notes: Each bar shows mean labor income of that subgroup compared to the mean labor income of the country. The U.S. values are highlighted in black. Values are ordered from the highest to the lowest.

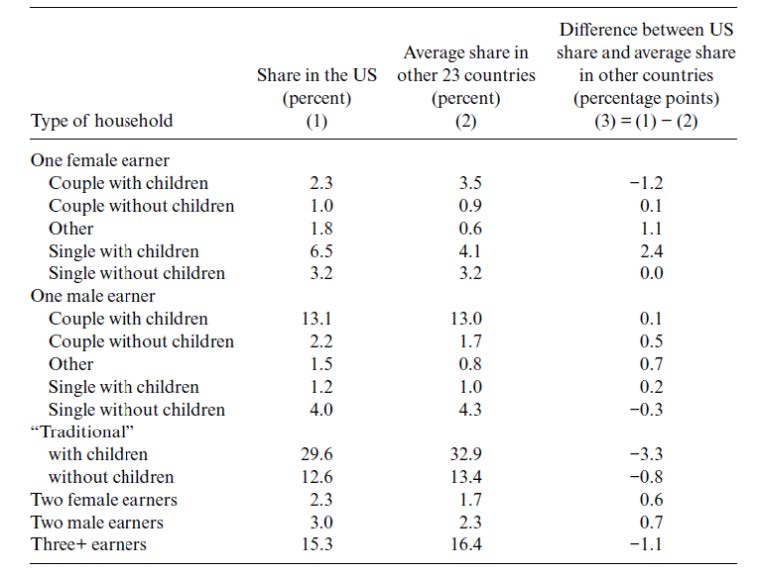

Finally, the answer to our third question, about variation in the prevalence of the subgroups is also, in short, no; the composition of the U.S. is not unusual. In Table 1 we report population shares of each of the 15 subgroups in the U.S., alongside the (unweighted) average shares across the 23 comparator countries. The U.S. shares diverge by more than 2 percentage points in only two cases. The first case is the one-male-and-one-female earner couple with children (which we dub the “traditional” dual-earner household): about 30 percent of the U.S. population lives in such households versus 33 percent, on average, in the rest of the affluent countries. The second case is one female-earner households where that earner is single with children; in that case, about 6.5 percent of the U.S. population lives in that type of household but only 4 percent, on average, in the other study countries. In common parlance, the U.S. is slightly low on traditional dual-earner households, and slightly high on households headed by single mothers — specifically, households headed by employed single mothers. However, we conclude that the U.S. composition is similar to that of other countries. That is, a unique compositional structure does not explain the high level of overall earnings inequality reported in the U.S.

Putting this all together, we conclude that it is neither a very different pattern of household formation, nor unusually high (or unusually low) earnings of some specific groups that explain U.S. inequality. High inequality in the U.S. seems to be “embedded” in all types of households, implying that the problem is high inequality of earnings as such, not how such earnings are combined at the household level.

Table 1. Population shares of household types

Our findings, as always, prompted us to think about implications for policy research. First, public policies and institutions that shape earnings distributions — including minimum wage requirements, collective bargaining institutions, and other mechanisms that effectively place floors or ceilings on wage distributions — are understood to affect the distribution of individuals’ earnings. Our work, however, focuses on households’ earnings; those are shaped by the earnings of individual household members but also by the ways in which earners are bundled in households. Little if any research assesses the extent to which earnings-related policies and institutions shape household-level earnings — either directly, or indirectly by influencing household-level employment behavior or even household formation.

Second, the extensive cross-national literature on the policies and institutions that shape earnings distributions — often referred to as the tools of “predistribution” — has not, thus far, focused on how their effects might vary across subgroups of workers, much less across subgroups of households.

A rich and growing supply of institutional databases in combination with high-quality microdata such as the LIS data, available both across countries and over time, offers the basis for future studies that might tackle these questions.

Endnote:

The following countries were included in the study: Australia, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Russia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, United Kingdom, United States.

Read More:

- Measuring Distribution and Mobility of Income and Wealth

- In Search of the Roots of American Inequality Exceptionalism: An Analysis Based on Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Data

- The Three Eras of Global Inequality, 1820-2020, with the Focus on the Past Thirty Years

- Drawing a Line: Comparing the Estimation of Top Incomes Between Tax Data and Household Survey Data