January 10, 2022

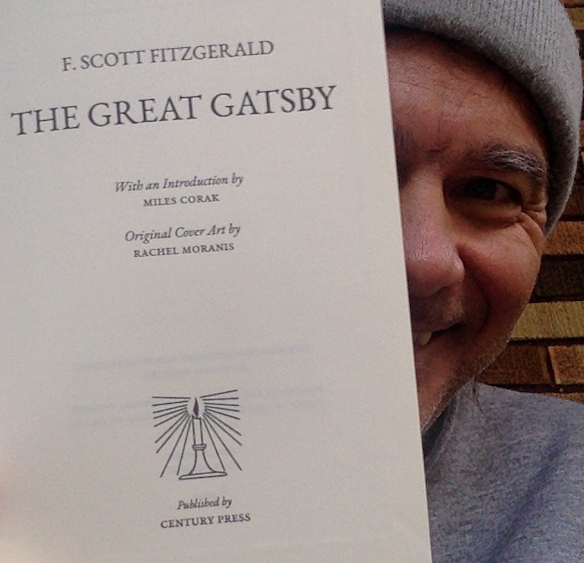

In this post, originally published on his website, Miles Corak explains how he came to write the introductory essay to a new edition of The Great Gatsby, now available from Century Press.

By Miles Corak

Last year I got an email out of the blue from Alex Simon, the founder of Century Press, asking me to write an introduction to The Great Gatsby, the first book his new publishing house planned to print. We talked and realized that we actually lived three blocks from each other.

I read a number of books to help me prepare for writing an introduction to this quintessential novel about the American Dream. First, of course, I reread The Great Gatsby but also a book by Sarah Churchwell, a professor of American literature at the University of London, titled Careless People: Murder, Mayhem, and the Invention of The Great Gatsby.

Then I read Thorstein Veblen’s The Theory of the Leisure Class, a book that had sat unread on my bookshelf for years and is best known for how the elite legitimize their status by fostering a culture of entitlement. I also read Michael J. Sandel’s The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good?

Sandel takes on the “rhetoric of rising” used repeatedly by Barack Obama to illustrate how our emphasis on meritocracy reconstructs the social divisions Veblen pointed to. Sandel argues that inequality breeds entitlement among the well-off and fosters shame among the many, and that the American Dream, with its emphasis on “you can do it,” is part of this framing, eroding the moral foundations of the public good.

I’m grateful to Century Press for the opportunity to introduce this great novel from an economist’s perspective, and to be part of its handsome leather bound and letterpress first edition. Below is an edited excerpt from my introduction.

“Our faith in possibility may be glorious, but it’s easy to forget that one possibility is always failure,” writes Sarah Churchwell, introducing the chapter in her 2014 book discussing Fitzgerald’s high expectations as he awaited the reviews of what he felt was his greatest work, a novel that he anticipated would vault him into the pantheon of American literature.

The reviews were not good: “F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Latest A Dud”; “a strange mix of fact and fancy”; “not a great novel … neither profound nor imperishable … [but] timely and seasonable.” The Fitzgerald scholar’s book, Careless People: Murder, Mayhem, and the Invention of The Great Gatsby, which is my source for these excerpts, uses the reviews at the time to support her insightful thesis, that The Great Gatsby can be seen as solidly situated in a specific time and place, with characters and plot having real-life counterparts.

Fitzgerald’s year in New York City—the places, the people, and even the lurid stories of a double murder in nearby New Jersey that was fodder for the papers—was easily recognized by his circle of friends and acquaintances writing those reviews. To them the novel must have appeared as much diary as it did fiction, as much journalistic as imaginative narrative. Been there, done that.

Yet as the decades passed, as gossip and headlines faded from memory, Fitzgerald’s book did not fade, and a century later it continues to resonate. To appreciate why, Churchwell’s thesis should be taken further: The Great Gatsby can be seen as solidly situated in a specific economic time and place, it is not just character, but also underlying strictures of social inequality, that drive the novel’s hapless protagonist to his ending. The novel remains as relevant to our age as it did for the Jazz Age because Gatsby’s economic time and place are also our times and places.

The story helps Americans, indeed citizens of all countries facing the challenges of rising inequality, wonder all the more about the hollowness of the metaphor legitimizing it, of the unkept promise of the American Dream.

The rich, Fitzgerald warns us early in the novel, are careless. Nick Carraway, the narrator who draws us intimately into the novel because he is far from omniscient, almost watching the story unfold with us, is beginning to fall in love with Jordan Baker, a friend of Nick’s cousin and Gatsby’s desire, Daisy Buchanan.

It was on that same house-party that we had a curious conversation about driving a car. It started because she passed so close to some workman that our fender flicked a button on one man’s coat.

“You’re a rotten driver,” I protested. “Either you ought to be more careful, or you oughtn’t to drive at all.”

“I am careful.”

“No, you’re not.”

“Well, other people are,” she said lightly.

“What’s that got to do with it?”

“They’ll keep out of my way,” she insisted. “It takes two to make an accident.”

An economist reading these lines, with admittedly a certain logic lacking romance, can’t help but see them as a metaphor for the Great Recession of 2008, an economic downturn that wreaked havoc across America, bursting the housing bubble, wiping out the wealth of the middle class, and throwing millions out of work and out of their homes.

Nick is the admiring, almost doe-eyed, government regulator captured by the dazzling titan of Wall Street who is driving the financial system with increasing recklessness. Accidents are inevitable, and it is the poor working stiff who pays the price, the driver bluffing his way out of responsibility.

This did not end well in our times, and not in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s. The party was to end in the bursting of a stock market bubble, the Great Depression announcing the end of the Jazz Age in 1929 and plummeting America and the world into a decade of turmoil. But of course, the novel is not really about how income inequality makes the macro-economy more volatile; it is about the corrupting role of inequality and about the illusions and lies used to propagate the myth of upward mobility, the myth used to justify the status of the already rich.

Fitzgerald embodies that status in Daisy’s husband, Tom Buchanan, a character constructed to check all the boxes of the confident and self-satisfied upper class. His physical presence is first on the list: a hard mouth, arrogant eyes, a great pack of muscle, “a body capable of enormous leverage—a cruel body.” This man has the power to kill, a power polished and civilized by all the other symbols of dominance that characterize Veblen’s Leisure Class—the pedigree of elite schooling, the stardom of the sporting field, and the wealth, the wealth without work that offers up houses and cars, and horses for playtime—but a raw and brutal power all the same.

And to go with it all, the intellectual acumen of a peanut, just enough literacy to be able to read silly books and suck up a pseudo-scientific world view that feeds self-satisfaction. Tom’s racism isn’t implicit or casual, its explicit and hard-wired. The eugenics movement is in the air, growing out of British colonialism, justified with simplistic statistics produced by Francis Galton, on its way to foster some of the worst horrors of World War II. Fitzgerald is telling us that Tom’s kind are quick to take it up to legitimize wealth without work, and whatever actions and lies it takes to keep the barbarians at bay.

Even so, this is a white man’s novel.

Black New Yorkers barely make an appearance, and when they do it is clear that Fitzgerald isn’t addressing racial inequality at all. Nick is given a fleeting glimpse of “three modish negroes,” passing him and Gatsby as they drive across the Queensboro Bridge on their way to lunch in Manhattan: “their eyeballs rolled toward us in haughty rivalry.” Not only are they going faster than Gatsby and Nick, the overtaking limousine is driven by a white chauffeur. Can you just imagine that!

Nick is thinking that this city is so crazy, so full of possibility, that it can even turn the racial order upside down, that anything could happen. “Even Gatsby could happen, without any particular wonder.” That’s how improbable Gatsby is, but I want you, Fitzgerald is telling us, to imagine that Gatsby is possible, that he is believable.

It is not simply that Fitzgerald isn’t addressing racial inequality; rather, he can’t even imagine how the struggles of Black Americans will underscore, as the decades pass, the myth of upward mobility that is the very subject of his novel.

In addition to overlooking racial inequality, Fitzgerald’s narrative marginalizes and simplifies the immigrant story. Nick makes repeated reference to his “Finn,” his Finnish housekeeper, who surely is a refugee to the United States from the civil war that racked Finland in 1918 during the aftermath of the Russian revolution and World War I, that led to tens of thousands dead, as many children orphaned, and a whole country on the brink of starvation. And there are the cameo appearances of the many others servicing the castles of his richer neighbors. They are likely no different in origin and aspiration than his “Finn.”

They are also no different than many migrants in our times, many of New York City’s Latin Americans having also fled corrupt and failed states, gangs and civil wars, in the hope of a better life for themselves and their children. Their plight too is central to the American Dream. While America’s gates were open in the decades before Fitzgerald wrote, they would be quickly closed shut. The immigrant dilemma has played out repeatedly in the decades since, with walls and cages becoming not just more apt metaphors than the open arms of Liberty, but sad and painful realities, a stain on the spirit of aspiration and mobility that is the American Dream.

The treatment of immigrants, like that of Black Americans, is both a cause and a product of inequality. There is nothing the rich desire more than serfs. Indentured servitude and outright slavery have their contemporary counterpart in the plight of so-called “illegal” immigrants. That’s the way Tom’s ilk has always liked their servants: insecure and precarious, willing to work at the lowest wage, continually looking over their shoulder as the risk of deportation tempers any demands for safe, sane, workplaces, for pay that offers a living wage. The deliverymen, the landscapers, the cleaning women, and the cooks of New York City are no different now than before. But they play only a bit part in the novel, their place in the social and economic hierarchy given and taken for granted.

There remains yet one more aspect of inequality that Fitzgerald only gets half right, that was certainly brewing in the 1920s, that the novel doesn’t just miss but mishandles: gender inequality.

The other thing Tom Buchanan possesses that signals his status and dominance is “the woman.” To be sure, the balance between the genders was in flux during the Jazz Age, and in retrospect we can draw what appears as a straight line back through a whole host of battles for workplace, family, and political rights, all the way to the winning of the franchise in 1920. But Fitzgerald’s novel portends nothing of the upward mobility of women and their battle for equality that so fundamentally changed post-war America.

Daisy may appear, in dress and intellect, a modern woman. Indeed, the Jazz Age fashion was a statement about a new womanhood, looser, flowing garments that broke through the strictures of the corset, symbolizing—literally offering—freedom and movement. But Daisy doesn’t actually do anything, she is a character without character, a cardboard cutout of the women of post-war America.

And that, very explicitly, is the point of this novel. Fitzgerald is reaching back for his conception of women, not pointing forward. Daisy’s only role is to be the object of male desire, a symbol of status. For the men of the Leisure Class, a woman who did nothing was another possession signaling social standing and projecting dominance. Ultimately, this is what Gatsby desires, why he demands complete fidelity and unquestioned love from Daisy, and why he is such an affront and threat to Tom.

The landscape of inequality, like that of New York City, is both the same and different. The time and place of The Great Gatsby are like our own, with growing inequality of resources, sharp divisions of status, the thwarted and corrupted personal goals they foster.

There are important parts of the novel that miss the mark, certainly; yet, it still rings true.

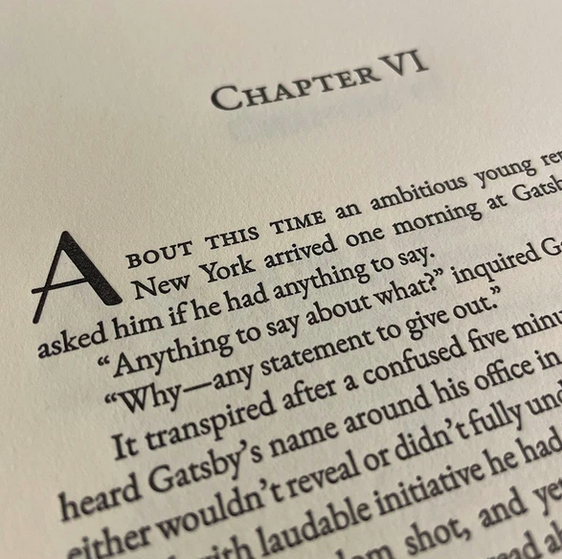

In Chapter VI, Nick offers a telling of Gatsby’s back story, his first days with Daisy, and how the inspiration of a romantic walk offers a vision of climbing a ladder, a ladder to a secret place: “he could climb to it, if he climbed alone, and once there he could suck on the pap of life, gulp down the incomparable milk of wonder.” Really, climbing a ladder to “suck on the pap of life”? It’s not a subtle metaphor, but Fitzgerald couldn’t make it any clearer that his hero is meant to embody not only a dream of upward mobility, but also an innocence about the possibility of its salvation.

The decades after World War II—after America had passed painfully through the Great Depression and total war, after these events shifted bargaining power and governance to allow a rewriting of the social contract, with robust unions fighting for fair wages, with the expansion of quality schooling, and with high taxes on top incomes and inheritances distributing the benefits of strong economic growth to the benefit of the many—were indeed decades of rising mobility with children from lower income families growing up, if not to reach the top one percent, to certainly do better than their parents.

Nick foreshadows all of this, as he turns his back on the careless and dangerous games played out by the rich and returns to his roots in the mid-west, to a comfortable middle-class life, a backstop that he takes for granted. Today, much has changed, as even the security of the middle-class is denied our most recent generations, the rich having rewritten the rules of public policy to rig the game and narrow the bottlenecks to prosperity.

Before Americans put a name to the “American Dream,” and before their elite propagated it to legitimize higher inequality, F. Scott Fitzgerald described the rot at its center, and the illusions it fostered among the talented, the ambitious, the aspiring. Illusion and rot are Jay Gatsby’s fate. That is the enduring lesson of his story, and the reason that this book of the 1920s, almost diary and documentary of one man’s New York, is a novel that continues to ring true.

Read More:

The Great Gatsby, published by Century Press

How the Great Gatsby Curve Got Its Name, by Miles Corak

The Great Gatsby, Then and Now, by Miles Corak

About the Author:

Miles Corak is a professor of economics at the Graduate Center whose research focuses on social mobility, inequality, and child rights. His ideas on the relationship between income inequality and intergenerational mobility led to what is known as the Great Gatsby Curve.