July 14, 2025

This is Part II of Stone Center Senior Scholar Paul Krugman’s series “Understanding Inequality,” which originally appeared on his Substack newsletter.

By Paul Krugman

For more than a generation after World War II income disparities in America were relatively narrow. Some were rich and many were poor, but there was nothing like today’s extreme inequality, economic fragmentation and class warfare.

Then, beginning around 1980, inequality surged, leading to the incredibly high levels we see today. As I documented last week, not only have the top 1% in the income distribution pulled away from the remaining 99%, but within the top 1% the top 0.1%, the top 0.01%, and the top 0.001% are pulling even further away. And this concentration of wealth at the top is corrupting our politics. Elon Musk’s claim that Trump would not have won in 2024 without him is quite plausible, while those currying favor with Trump by giving millions to his inaugural fund and buying his crypto-coins are clearly receiving favorable treatment.

I will discuss how we got to this point — but not in today’s primer, saving it for next week. For today I want to continue the discussion I began last week of the causes of rising inequality in America.

In last week’s primer, I asserted that the most important reason for rising inequality since 1980 has been a shift in political and bargaining power against workers. While globalization and technological change have certainly been contributing factors, the numbers just don’t justify the claims that they are the primary reasons for rising inequality in America. Mostly it was about power.

I’ll now begin to flesh out that argument. For the most part, however, today’s primer will be about the drivers of rising inequality between 1980 and 2000. Why stop there? Because I need more space and time to adequately discuss the effects of “financialization” and the rise of giant tech fortunes, which mostly kicked in after 2000 and accelerated the concentration of wealth at the very top. I’m well aware that these are also the factors driving today’s headlines. But the surge in inequality before 2000 set the stage for the oligarchic moment we’re now experiencing.

I’ll discuss the following:

1. Why power is key to the inequality story

2. Unions and why they matter

3. The rise of the imperial CEO

How power joined the conversation

Until the 1940s institutional economics, which among other things put a lot of emphasis on power relations, was an important strand of American economic thought. But after the war, for several reasons — including, ironically, the rise of Keynesian economics (but that’s another story) — it was largely driven out by mathematical models in which profit- and utility-maximizing individuals lead markets into equilibrium, leaving little room to talk about power. Also, there didn’t seem to be much reason to spend a lot of time analyzing income inequality, partly because inequality was relatively low and partly, let’s face it, because academic economists were under some pressure to avoid sounding “socialist.”

But the rise of inequality since 1980, in addition to bringing the whole subject into focus, has made it clear that simple supply-and-demand stories are often inadequate for explaining how much people are paid and why they are paid different amounts.

So let me talk about four key pieces of evidence that made me and many other American economists begin to take the role of power in income distribution seriously.

Sticky wages: In 1992 Truman Bewley, an economist at Yale who had previously specialized in highly mathematical economic models, became obsessed with a question that became the title of a 1999 book: Why Wages Don’t Fall During a Recession. During a recession, there are many more people seeking jobs than the number of jobs available. Employers could clearly hire new workers at substantially lower wages than they are paying their current work force, so they could replace existing workers with new, cheaper employees — or demand wage cuts from workers who would have a hard time finding new jobs.

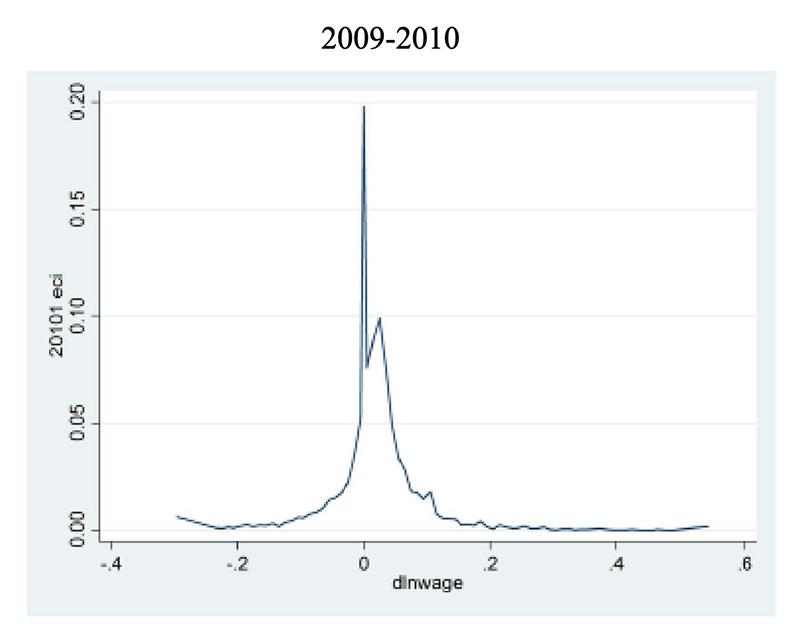

So why don’t wages fall? Because they don’t, except under very extreme conditions. For example, a 2015 study of the distribution of wage changes in periods of high unemployment found this for the years immediately after the global financial crisis. In the following graph, the vertical axis is the share of workers receiving a given wage increase (in logs) from 2009 to 2010. For example, a 0.2 share of workers (20%) saw no change at all, while 10% received modest wage hikes:

The distribution of wage changes in a depressed economy

As you can see, there was a big spike at zero: many workers received no wage increase. But almost none faced an actual pay cut. Why?

Bewley did something very unusual for an economist: He went out and talked to people, especially businesspeople. What they told him was that wage cuts were very bad for the morale of workers, who would feel that they were being taken advantage of, and the cost savings from wage cuts weren’t worth it.

In other words, workers’ perceptions of fairness matter a lot. But what determines what they consider fair?

The Great Compression: As I explained last week, the relatively equal distribution of wages and other income that prevailed for several decades after World War II didn’t evolve gradually. It happened more or less suddenly, with a rapid compression of income gaps during the war and maybe a few years beyond.

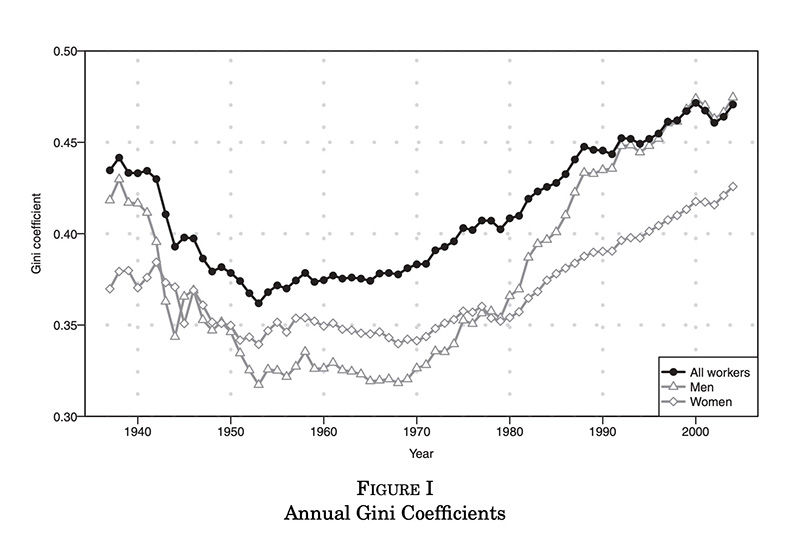

Kopczuk, Saez, and Song have a very useful picture of the change in wage inequality over time based on Social Security data. They use the Gini coefficient — not my favorite measure, but good enough for today’s purposes — to measure inequality, showing the same sharp fall, extended period of stability, then big rise after 1980 we saw last week. Remember, a lower Gini means lower inequality:

There was a precipitous decline in inequality during the 1940s. That decline can be attributed in large part to wartime controls, which limited wage increases but were much more binding for higher-paid workers. These controls were lifted in 1947 but reimposed during the Korean War.

So the initial plunge in inequality isn’t hard to explain. What economists find much more puzzling is the fact that wage inequality didn’t spring back to “normal” once controls were lifted. Instead, relatively equal wages persisted for decades, not getting back to pre-Great Compression levels until the late 1980s.

Somehow, a period of relative wage equality seems to have created a new normal for pay differentials, which became the standard for several decades. I’ll talk later about what enforced the new norms (spoiler: unions had a lot to do with it), but for now the point is that income inequality seems to be less determined by the invisible hand of the market and more by the visible hands of workers and employers bargaining hard than Econ 101 might suggest.

But if new norms led to higher wages at the bottom, shouldn’t that have led to a lot of unemployment? Well, that brings me to the next piece of evidence.

Minimum wages: America has a national minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, but that rate hasn’t been raised since 2009. In the years since, inflation has eroded that wage in real terms to the point where it’s probably irrelevant to the economy.

However, many states and some cities have their own, often much higher minimum wages. And one unintended but useful consequence when local governments raise minimum wages is to provide evidence on these minimums’ effects. If New Jersey raises its minimum while Pennsylvania does not, comparing employment trends in neighboring counties gives you an estimate of the minimum wage’s effect on employment. Econ 101 says that a higher minimum wage should cost jobs, but does it?

David Card and Alan Krueger did a pioneering study based on this insight in the early 1990s, and found that the NJ minimum wage hike had no visible effect on jobs. Since then there have been many, many such studies, and they confirm the Card-Krueger result.

What do these results mean for income inequality? I don’t think that minimum wages per se are a large part of the story of rising inequality. But their failure to destroy jobs tells us is that there’s a lot more “wiggle room” in wages than simple supply-and-demand stories suggest, and hence more room for power and social norms to play important roles.

And then there are employees who basically set their own pay …

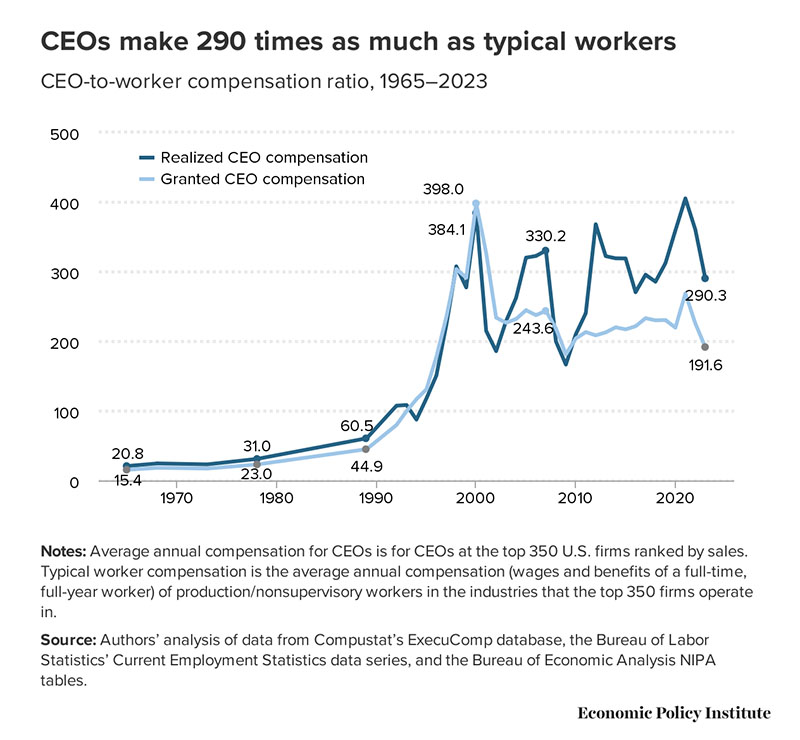

Executive pay: How does a company decide how much to pay its CEO and other top executives? They can’t just look at the going market rate. Even a cynic has to admit that some CEOs are better than others, and the value of a particular executive’s talents may depend on the specifics of the company they’re hired to run. In practice executive pay is set by compensation boards appointed by … the executive themselves.

The potential for self-dealing has always been obvious. Still, in the 1960s CEOs were paid “only” around 20 times as much as their workers. Then things, well, changed. Here’s the ratio of CEO pay to the earnings of typical workers:

I don’t think there’s a plausible explanation of this pay explosion in terms of globalization or technology. So something else, presumably involving power and norms, changed.

Unions

The puzzle of the Great Compression isn’t the fact that it happened — prices, wages, and many other aspects of the economy were subject to extensive government controls, not just between Pearl Harbor and V-J Day, but into 1947 and again from 1950 to 1953. The puzzle is that it persisted so long. What sustained the new normal?

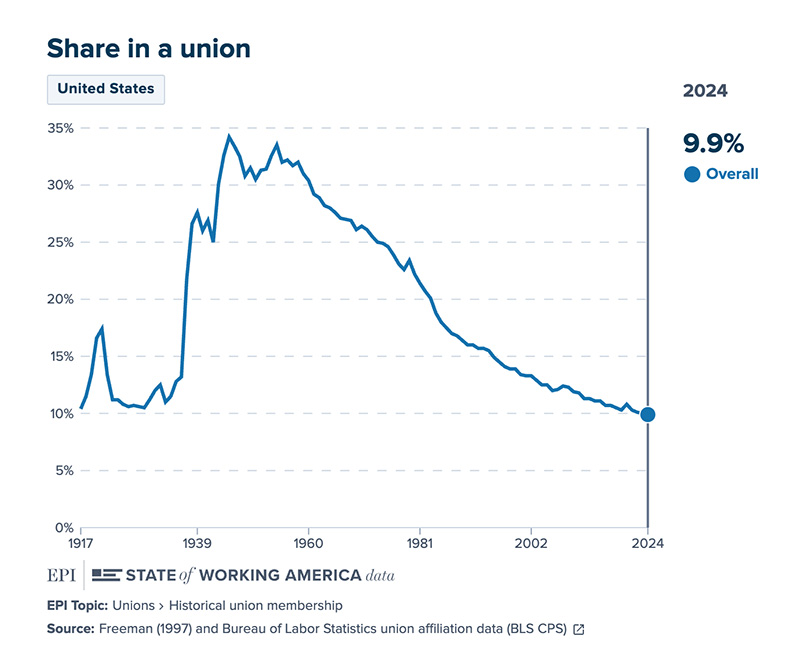

A large part of the answer, surely, was the existence of a powerful union movement. Union membership soared during the late 1930s and rose even higher during the war. Unionization then declined gradually but was still a quarter of the work force as late as 1973:

Even these numbers understate the effect unions had on American workers. Companies that weren’t unionized had to worry about possible organizing efforts, so many paid their workers as if they were unionized — a sort of penumbra effect covering even the unionized. Unions also set norms that tended to affect wages even when there was no immediate threat of a union election.

A classic 1984 book titled What do Unions Do? by Richard Freeman and James Medoff argued that unions are a strong force reducing wage inequality. Not only do unions raise wages for their members, they tend to raise wages more for less well-paid workers with less formal education. There has been a huge follow-up literature, which I won’t even try to summarize except to say that a few caveats aside — notably, the picture for women is less clear than it is for men — for Freeman and Medoff have basically been vindicated.

Which is sad and ironic, because just as Freeman and Medoff were documenting the ways unions made America less unequal and, I’d say, fairer, union power was rapidly collapsing.

Why did unionization decline? I suspect that many readers will assume that unions used to be strong because big unions were mainly in manufacturing, and America has deindustrialized. If deindustrialization was, as I’ve argued, mostly unavoidable, wasn’t the decline of unions inevitable?

No. It’s true that manufacturing used to be more unionized than the rest of the private sector — 32 percent in 1980, versus 15 percent elsewhere. But manufacturing is now much less unionized than it was. Even more to the point, the reason the big unions used to be in manufacturing was that industrial companies like General Motors and Ford were also the biggest employers.

Today, we are overwhelmingly a service economy in which the biggest employers are retail companies: Walmart with 1.6 million workers, Amazon with 1.1 million. There’s no fundamental reason these companies couldn’t be unionized — actually, UPS, which is the third biggest employer, mostly is. But these companies grew big in a political environment that was hostile to union organizing and permissive toward corporate efforts to squash unions, often using illegal tactics.

Oh, and unions continue to represent large numbers of workers in other advanced economies (which also have much lower inequality than we do).

So if unions were a major force limiting inequality, which they were, their decline was essentially a political phenomenon. Why did the political environment shift against them so strongly? See my next primer …

Imperial CEOs

In 1955 Fortune published an article titled “How top executives live.” The answer, of course, was “pretty well” — but not nearly as lavishly as they had 20 years earlier. In general, CEO’s lives sound incredibly modest by today’s standards. And I’m not sure how seriously to take some of the cultural observations: “Extramarital relations in the top American business world are not important enough to discuss.” Oh, kay.

Obviously the material and cultural universe of the business elite has been utterly transformed. But why? It’s hard to see either a globalization or a technological explanation, nor is it clear why it’s more important now that corporations have good leaders than it was in the past.

In general, the people determining an executive’s pay — the corporate board or a specially appointed compensation committee — have neither (a) the knowledge nor (b) the incentive to determine what the CEO should be paid. Furthermore, they are often either appointed by or closely tied personally to the CEO. So to a first approximation CEOs determine their own pay. Why, then, did they “only” feel able to pay themselves 20 times as much as their workers in the 1960s, but ten or more times that much today?

Again, the most likely explanation is political. Before the 1980s huge payouts to executives could generate a major public backlash, which companies might not want to incur. Executives themselves may have been less inclined to court rancor when facing high marginal tax rates, so they couldn’t keep much of what they gained.

But the political winds shifted, and there may well have been a growing sense of safety in numbers. If everyone else is negotiating huge pay deals, why not do it yourself?

So we became a nation of corporations ruled by imperial CEOs who pay themselves incredibly large sums.

But even that wasn’t the end of the story.

Towards today’s oligarchy

Beginning around 2000 America saw the emergence of truly enormous fortunes, particularly in finance and technology. Part of the explanation for this abrupt shift lies in technological changes, including the rise of the internet. This, along with financial deregulation, enabled an explosion of financial wheeling and dealing. That explosion in the “financialization” of the economy ultimately enabled the growth of the huge tech fortunes. And with it came the vast increase in the political power of money and the saga of Elon Musk and Donald Trump.

But it will take time to tell that story. So wait for next week.

Read More: