December 13, 2024

In this post, Stone Center Senior Scholar Paul Krugman looks at U.S.–EU divergence in the technology sector, and the role of geographic clusters. The post originally appeared in his Substack newsletter: Krugman wonks out.

By Paul Krugman

And now for something completely — OK, mostly — different. Today’s post isn’t very political. Also, it isn’t one of those discussions about how influential people have basic facts wrong; I’ll do plenty of those, but in this case I’m tackling a serious mystery and offering an answer that could well be wrong.

So, here we go.

One of the things that frustrates those of us who believe that the electorate made a terrible choice last month is that U.S. voters seem to be more or less the only people in the world who believe that America has a bad economy. Other nations look at our performance with envy and even alarm. Indeed, the European Commission recently released a report by Mario Draghi, the former president of the European Central Bank (and the man who saved the euro) calling for urgent action to close the gap.

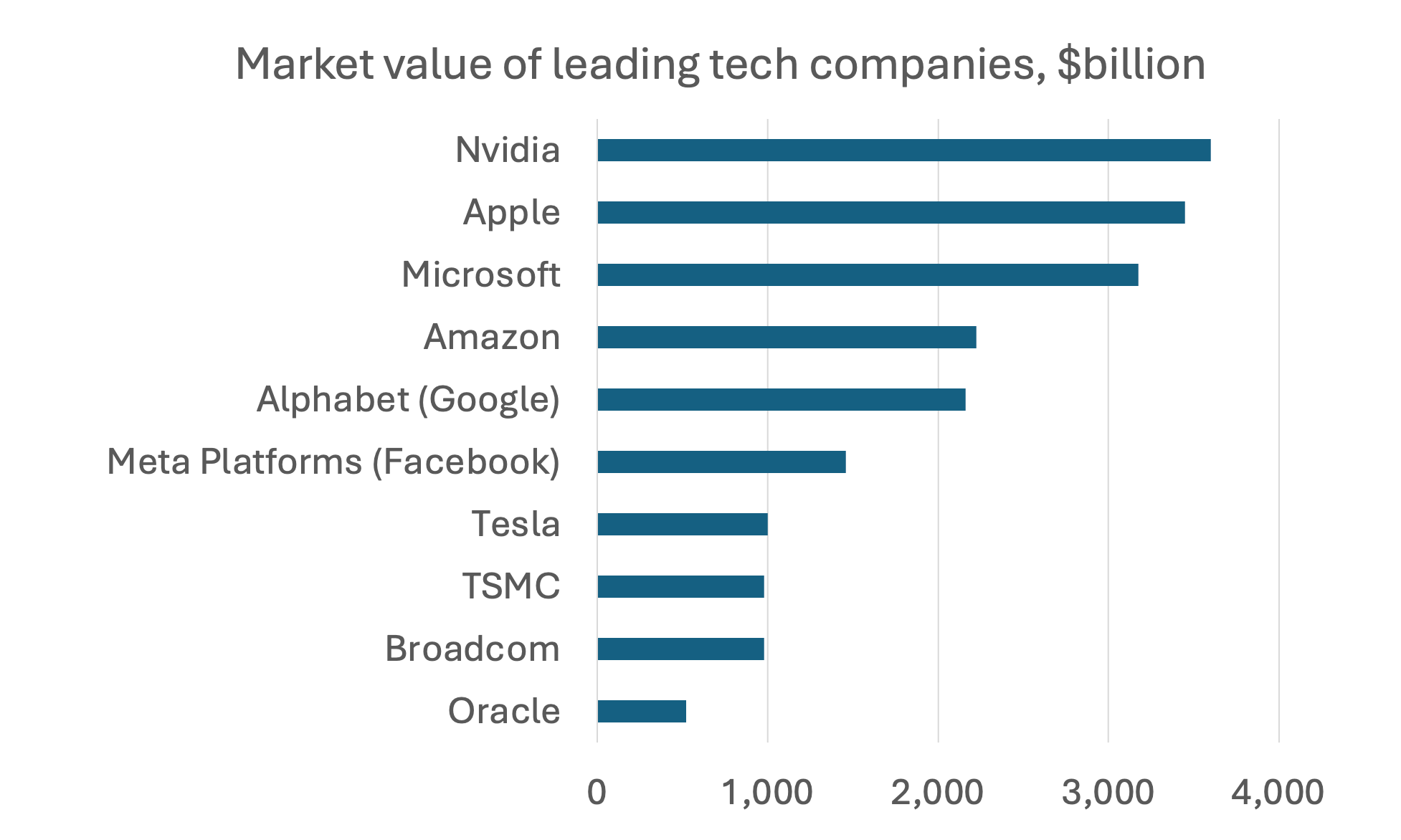

Much of the focus is on U.S. dominance in digital technology. It’s not hard to see why. Look at a list of the ten tech companies with the highest market valuation as of mid-November. With the exception of the Taiwanese semiconductor giant TSMC, all are American; no European company even comes close:

But there’s a funny thing about that list, which goes oddly unmentioned in the Draghi report and every other survey of U.S. tech dominance I’ve read, such as last week’s long read in the Financial Times. It’s true that TSMC aside, all big tech companies are American. But America is a big country, yet our tech giants all come from a small part of that big nation. Six of the companies on the list are based in Silicon Valley — and while Tesla has moved its headquarters to Austin, it was Silicon Valley–based when it made electric cars cool, and the best-known new Tesla product since the Avignon papacy move to Texas has been the Cybertruck:

The other two are based in Seattle, which is sort of a secondary technology cluster.

So what I’m going to do today is offer a heterodox take on U.S. tech dominance. Almost everything I read focuses on things like excessive regulation in Europe, a financial culture that is willing to take risks and so on. I’m not saying that none of this is relevant. But one way to think about technology in a global economy is that development of any particular technology tends to concentrate in a handful of geographical clusters, which have to be somewhere — and when it comes to digital technology these clusters, largely for historical reasons, are in the United States. To oversimplify, maybe we’re not really talking about American tech dominance; we’re talking about Silicon Valley dominance.

To the extent that this is true, I think it has some important implications. These will have to go in another post, because this one is already too long. But in any case, let’s look at the background.

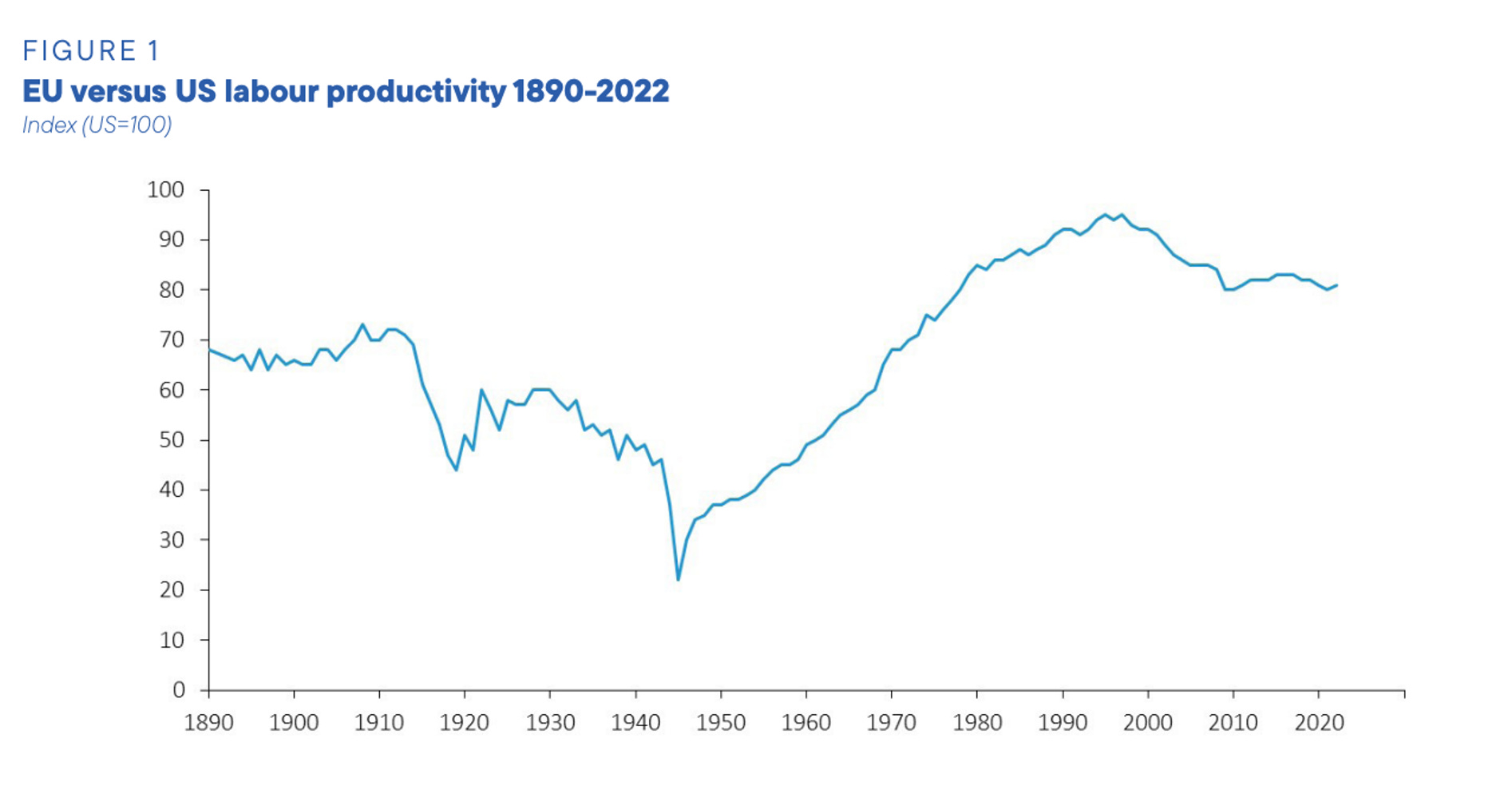

Go back a generation, and the U.S. economy, while huge and powerful, didn’t look all that exceptional. To a first approximation, all advanced countries seemed to be on the same technological level and had roughly the same productivity, that is, output per person-hour. Europe had lower G.D.P. per capita than the United States, but that was because Europeans worked fewer hours, which in turn largely reflected policies mandating that employers provide vacation time, while America was (and is) the no-vacation nation. Europeans had less stuff but more time, and it was certainly possible to argue that they were making the right choice.

Starting around 2000, however, America surged ahead. The Draghi report opens with a chart that puts this relative surge in historical perspective, showing how it partially reversed the great productivity convergence that followed World War II:

So can we explain America’s surge and Europe’s lag?