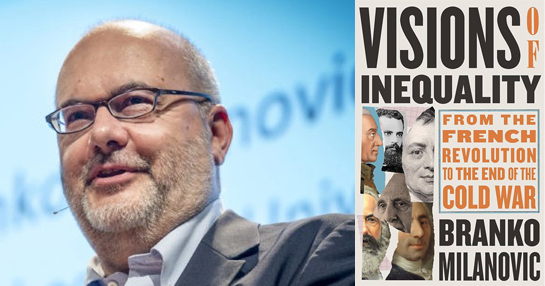

In this interview, Stone Center Research Professor Branko Milanovic discusses his recently published book, Visions of Inequality: From the French Revolution to the End of the Cold War. The book delves into how six economists over two centuries — François Quesnay, Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Karl Marx, Vilfredo Pareto, and Simon Kuznets — thought about the income distribution during their own time, and how they expected it to change.

How did you choose this particular time span and these particular authors? Also, why did you group the more recent scholars together in a single chapter?

Milanovic: I think the choice was actually pretty simple: these are the most important people in political economy. Essentially, you start with Quesnay and Smith; most scholars identify one or the other as the founder of political economy. Then you go naturally to Ricardo and Marx, and then you come to the people who have really developed income distribution studies in the way that we see them now, Pareto and Kuznets, but who also had other interests.

I grouped the more recent authors together because I wanted to end with the end of the Cold War. From the French Revolution to the end of the Cold War is a nice, round two hundred years: 1789 to 1989. I didn’t want to go into the current debates, which have had participants including Piketty, and all the issues and work that he brought up. He’s mentioned in the epilogue in a very favorable light, but as for the other recent authors, there were no figures of the stature of the first six. Of course, Tony Atkinson comes to mind as a potential number seven, but in my opinion, although he was of course excellent in his empirical work, he did not have a political dimension that I believe income distribution studies should have, or a sociological dimension or even philosophical dimension as in the case of Marx and Smith.

There were two other authors that I originally considered possibly including. One was Plato, and I still believe it could have been done, but there’s a huge time gap between Plato and Quesnay. The second, whom I mention at the end of the chapter that deals with more recent developments, was Samir Amin. He’s one of the founders of the structuralist — or, if you want, Neo-Marxist — World Systems Theory. I read Samir Amin when I was quite young and I was very influenced by him. But as I was thinking of including him, I realized that the work that I knew and liked very much was his early work. A chapter on him would be short. So he’s included, but not at the same level as the six.

In the book you take on each thinker’s own perspective — essentially, you examine the topic of inequality through their eyes. Why did you decide to remain indifferent, as you say in the introduction, to the various thinkers’ normative views on inequality?

Milanovic: I wanted to study the evolution of thinking of inequality more or less like a historian. I really tried to think on their own terms. My approach is basically noncritical in the sense that I essentially take their point of view.

If I were discussing the normative part, I would have been led to select different authors. People would ask, “Why not Rousseau?” Or “Why not Rawls?” But neither of them has anything empirical to say about income distribution. Rawls has principles, but has he said anything about income from capital, income from labor? Has he said, “Is the income distribution Gini going up or down?” No.

This is a book about empirical work. What are the forces that actually determine income distribution, and how do you see the evolution? It’s empirical, and analytical. These authors didn’t have the data that we have today, so they were not empiricists in the sense that we see empiricism today, but they were analytical.

Do you think readers will find it surprising that you avoided even Marx’s normative positions?

Milanovic: I know it’s a little bit controversial, but generally speaking, people who have read Marx know that Marx was not interested in equality or inequality in the way that we are today. The interest that Marx and Engels and Marxists had was in the abolition of classes, which meant the end of capitalism, which meant the end of private property. So their activism — and Marx of course was an activist throughout most of his life — was organized with that ultimate goal in mind.

Sure, you — of course, I mean Marx — work for improvements in the condition of the working class. You highlight how bad the situation is. You support the trade union movement. You do all of that. But their ultimate objective is not the amelioration of capitalism, or improvement in the position of the working class within capitalism, as essentially social democratic parties say today. The ultimate position of Marx is the abolishment of capital-labor relations and transcending capitalism.

Marxists were skeptical about points of view that would emphasize the issue of equality or inequality because they thought that you would essentially exhaust your energy on that, whereas really your energy should be directed toward a higher goal, which is the abolition of the class system. It’s wrong to believe, as some people do today, that if you go all the way to the left — and Marx is sort of all the way to the left — that these people must be even more in favor of equality than others. That’s not the case, because it’s only the case if you accept the existence of capitalism as a natural and permanent system. But since they didn’t accept it, that logic that the more to the left you go, the more egalitarian you are, actually stops. It collapses there.

Your chapter on Ricardo discusses what you identify as the “Ricardian windfall”: the idea that lowering inequality is a tool for higher growth. Does Ricardo say that the growth of the middle class is a condition for economic growth?

Milanovic: That part on the Ricardian windfall, I don’t think that was actually ever noticed before, simply because people have studied Ricardo from alternative perspectives. Maybe I was lucky to have decided to study him from the income distribution perspective. Ricardo’s objective was to increase profits for capitalists in order that these profits can be reinvested, and growth accelerated.

What is interesting from the point of view of someone who is interested in inequality is that this objective can be reached only if the income distribution changes in such a way that those at the top — those who are landlords and who, in those days in England, were about 1.5 percent of the entire population — get squeezed, get less and capitalists get more. The capitalists were not middle class because there were not that many of them. In that sense, the income distribution measured by today’s tools, like the Gini coefficient, would improve, because the top 1 percent would get less and the middle, or the upper middle, would gain more. In some sense, what Ricardo is offering to his readers is a windfall, because you both improve distribution and you improve growth.

There was a long period in the twentieth century when inequality studies seemed to slow — but then, over the last few decades, there’s been an explosion in new research. What is behind this change?

Milanovic: After Kuznets’ work in the mid-’60s until 1990, in my opinion, we didn’t have very much. It’s tied to having a political view about the segmentation of society. Is society segmented, as Quesnay says, because there are different legal classes? Or is it — as Smith, Ricardo, and Marx say — because these classes have different access to assets? Or, in the case of Kuznets, is it about urban manufacturing workers versus farmers?

And then suddenly we don’t have classes anymore. We just have people. That was, in my opinion, driven by the Cold War. I call it Cold War economics, because to the Soviet claim that they had abolished classes, the U.S. responded with the same claim: Everybody’s the same. One guy has capital. Another guy is a laborer. But they behave the same. They’re both agents. They both optimize under the conditions of given price structures, of given endowments. I think there was sort of a movement in economics — partly driven by the development of economics, but partly driven by political reasons and the sources of funding provided by the rich — that destroyed the possibility of having inequality studies in the way that I define it.

And then we returned after 1990s to, basically, the class structure of society. It was brought by Piketty, but there were of course political reasons behind that as well. Two things are quite important in Piketty’s work: the introduction of 1 percent and the emphasis on capital incomes. That was not done before, and capital incomes had been kind of disregarded for thirty years. Lots of work was done either on total income or on labor income, skill premium, difference between different types of labor, gender inequality, and earnings, but not on capital incomes. There is a political reason why capital incomes were ignored. So he brings back two elements there. His work was important because it fell at a point in time after the global financial crisis when the middle class realized, especially in the U.S., that it had not done as well as they were expecting to have done, because they were borrowing a lot. On the other hand, the top 1 percent had done very well.

In my opinion, that was a watershed moment where we actually went back to studying either the elite or class structure and incomes. That’s why in the epilogue, I speak about a revival, a renaissance in some sense, of inequality work. It’s now at a much higher level, because we have much more information, more data. And we don’t have this political constraint, nor do we have the ideological constraint that I think most economists had before, not to study the income distribution.

Where do you see inequality studies as going next?

Milanovic: I see three good developments. The first is the return to a focus on class structure and capital and the elite, brought largely by Piketty’s work. The second is a focus on global inequality. One of the obvious scopes of income distribution studies is global; it’s no longer only national. And we have the data, of course.

And the third is studies of the past. We know very little about income distributions in the past societies, but now we are increasingly using archival sources. We are using tax data to the extent that they existed. And we are using so-called social tables, which list all the key social groups and their average incomes to study history of income inequality, which of course would inform the present. For example, the recent paper by Guido Alfani and Alfonso Carballo about inequality in the Aztec Empire is quite extraordinary. And we learn about the type of social structure that existed. We learn about the top classes. Were they, for example, landlords or nobility or viziers and government officials?

Are there any further lessons that you’d like readers to take away from this book?

Milanovic: The lesson is that we should be able to critically look at our own work. In other words, the type of inequalities that we discuss today are the inequalities that are obviously relevant from today’s perspective. And that’s why we have done much more on racial inequality and gender inequality than in the past.

The classical authors did not pay sufficient attention to slavery, racial inequality, and gender inequality. Smith and Marx did write on slavery but not too much. Smith believed it was unjust and unproductive but could never be abolished because rich people, who own slaves, control governments too. Marx was decidedly against. This is, among other reasons, why he supported the North in the Civil War. But he saw it a bit differently: what the North accomplished was the elimination of a less efficient economic system (slavery) by a more efficient (capitalism) system, using, when needed, violence. He thought the same fate awaited capitalism in its turn.

Regarding gender, Smith discusses it a lot in his Lectures on Jurisprudence, notes of his lectures as taken by students. He looks at the condition of women in different societies. There is a whole chapter on it. He considers, for example, than the Catholic ban on divorce improved the within-family power of women. Men could not divorce women at will, so they had to take their opinions more seriously. Marx writes less explicitly about gender inequalities. The thinking was that they are inseparable from capitalism and other class societies, and that only a social change (revolution) would establish gender equality.

Now we pay a lot of attention to racial inequality and gender inequality. And to global inequality. The work on between-country inequality — in other words, work showing that individuals with the same skills, intelligence, and work effort who live in different countries might have vastly different incomes — was not something that was studied before we had global inequality data. But we knew why people came to the United States. If you come to the U.S., you are the same person, but you would have a much higher income than if you had stayed in Poland or in Russia. But it was not put in an overall context. It was anecdotal evidence. Now, we can study these “location premiums” empirically, and we can ask an important question: How far does the ideal of equality of opportunities extend to? Does it stop at the border? Or does it spread to the entire world? If the latter, why are we not for free migration?

To conclude, we should not be unaware that there could be other types of inequalities that we do not see as future societies might.

Read More: