A new study coauthored by Stone Center postdoctoral scholar Jaquelyn Jahn finds that despite overall declines in arrests in the early months of the pandemic, the vast differences in policing experienced by residents of Black and white neighborhoods persisted.

As Covid-19 spread rapidly throughout the United States in March 2020, mayors across the country issued stay-at-home orders, many of which were enforced by local police departments. The social distancing orders continued throughout the spring and summer, overlapping with a period during which demands for systemic change in policing — fueled by widespread protests in the wake of police killings of Black men and women — became a topic of national conversation.

A new study by Stone Center postdoctoral scholar Jaquelyn L. Jahn, Boston University’s Jessica T. Simes, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Tori L. Cowger, and University of California, San Francisco’s Brigette A. Davis, examines how arrest rates changed in the six months after stay-at-home orders were implemented in four diverse cities: Boston, Charleston, Pittsburgh, and San Francisco. The study, recently published in the Journal of Urban Health, uses interrupted time series models with census tract fixed effects to analyze arrests in Black and white neighborhoods in the 24 weeks following stay at home orders. It provides the first estimates of urban neighborhood arrest rates during the pandemic.

Racial and ethnic disparities in arrest rates are well established, the authors note. “Research on the degree of police contact in Black neighborhoods describes a landscape of ‘divergent social worlds,’ where Black communities experience such extreme levels of police contact that there are not enough white neighborhoods to draw relevant comparisons,” the authors write. The structural racism in policing has significant implications for racial health equity; police encounters have been shown to have negative effects on physical and mental health. (Read about Jahn’s work on the mental health impact of police stops and the connection between police violence and pregnancy loss, and on preterm births in a locality and its rate of incarceration.)

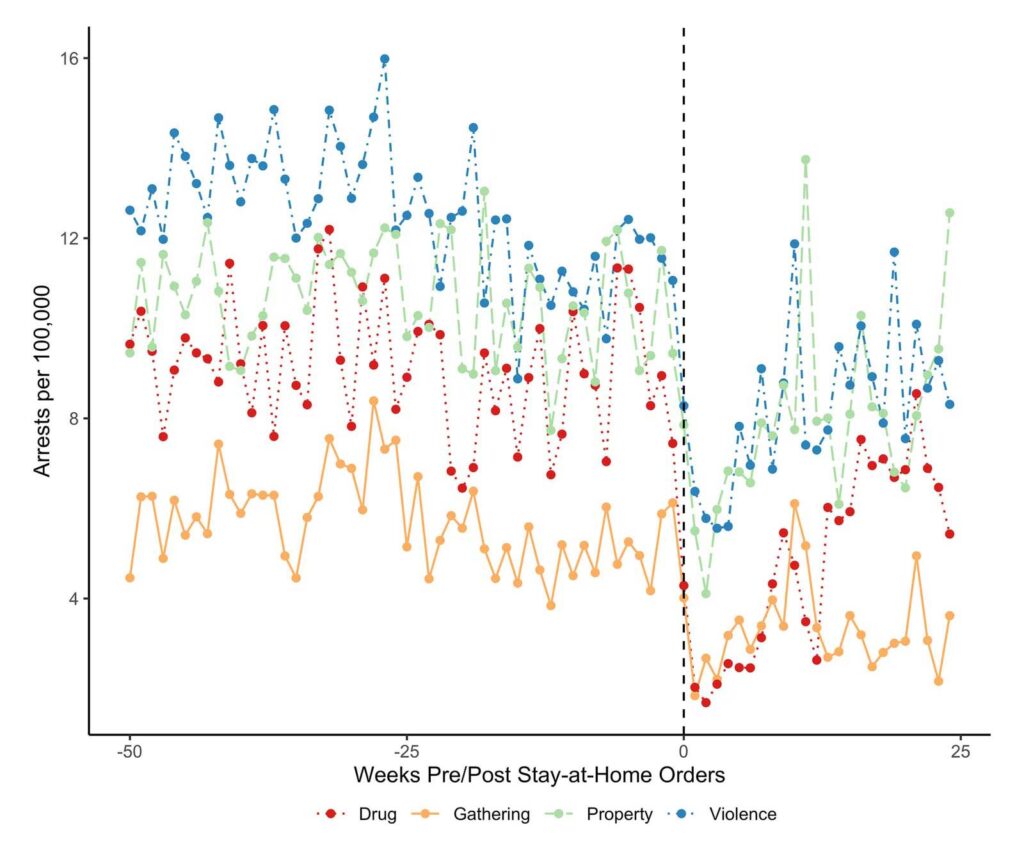

The first question examined by the researchers was the broad impact of the stay-at-home orders on arrests. Overall, arrest rates fell by 39 percent in the weeks following the orders, compared to average rates in the previous year (2019). Weekly arrest rates for violent offenses fell by 35 percent, for property-related offenses by 21 percent, for drug offenses by 54 percent, and for arrests for gatherings and public disorder by 45 percent. Ten weeks later, arrests for most of these offenses began to rise, approaching the previous year’s levels. However, for most types of arrests, the rates remained lower than before. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Time trends in types of arrest before and 24 weeks after stay-at-home orders. Census tract rates of drug, gathering, property, and violence arrests in Boston, Charleston, San Francisco, and Pittsburgh for each week from January 2019 to August 2020

Copyright © The New York Academy of Medicine 2022

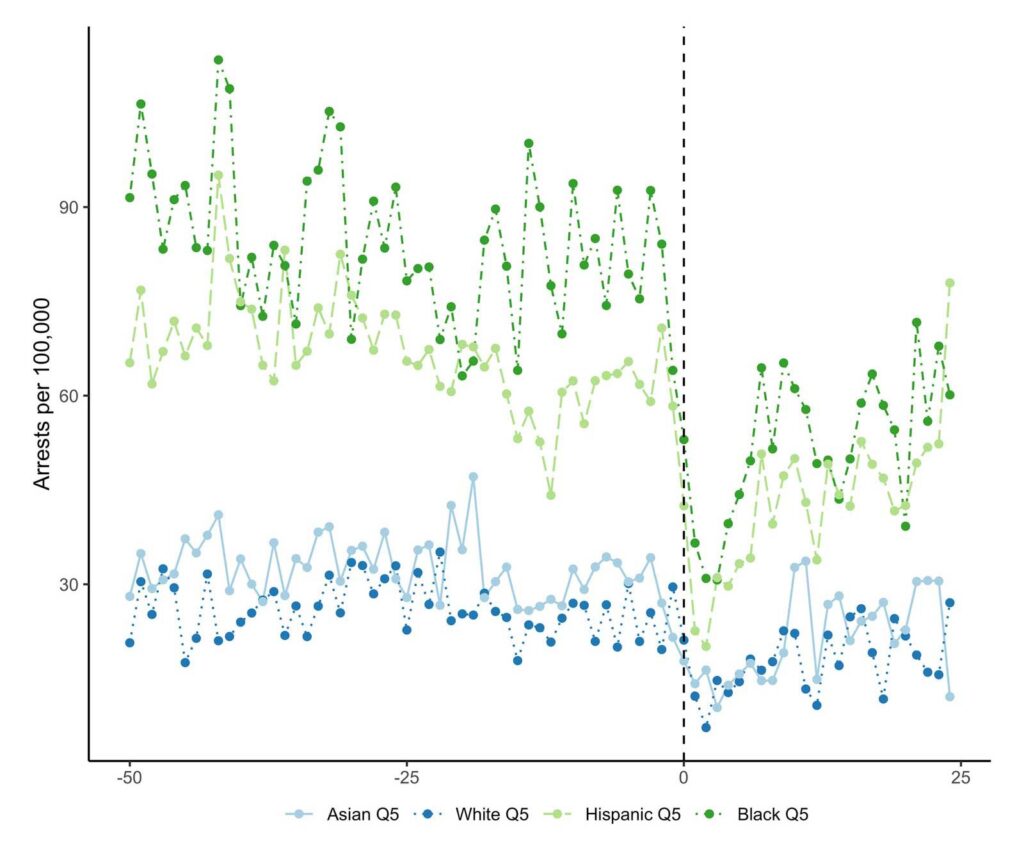

The researchers next looked at the effect on racial disparities in arrest rates. They found that despite the overall declines, racial disparities remained. On average, neighborhoods with the highest percentages of Black residents fell to 52 arrests per 100,000 people from 85 per 100,000 people compared to the prior year, while areas with the lowest percentages of Black residents fell to 15 per 100,000 people from 23 per 100,000 people. The declines were significant across neighborhoods with different racial compositions and for nearly all arrest types. However, there was neither an immediate nor a sustained change in arrest rate disparities between Black and white neighborhoods, compared with the disparities in the prior year. In fact, the racial disparities were so large that despite the decline in arrest rates in Black neighborhoods in the weeks after the stay-at-home orders were implemented, these rates only very briefly drop below pre-pandemic rates in white communities (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Time trends in rates of arrest before and 24 weeks after stay at home orders, stratified by census tract racial composition. Rates of arrests in census tracts with the highest quintiles of Asian, White, Hispanic, and Black populations in Boston, Charleston, San Francisco, and Pittsburgh for each week from January 2019 to August 2020

Copyright © The New York Academy of Medicine 2022

The authors conclude that the sharp declines in arrests in Black neighborhoods indicate excessive policing in those places, especially given the large declines for arrest types involving the greatest discretion (such as arrests related to drugs and public disorder, which declined by 54 and 45 percent, respectively). And these declines in arrests may also be part of larger efforts cities made to reduce incarcerated populations to prevent Covid infection. “The crisis conditions of a lethal infectious disease called into question the public health provision, safety, and ethical status of criminal justice institutions,” the authors write. “When the pandemic is over, these public health and ethical questions will remain.” However, the authors also note the entrenched structural racism that is revealed by the persistent racial inequities in arrests despite declines. “[Even] under these conditions and a dramatic decline in overall arrest rates, the racial-spatial divide in police contact persists in these four U.S. cities.”

Read the Paper: Racial Disparities in Neighborhood Arrest Rates during the COVID-19 Pandemic