March 13, 2025

A recent article in The Economist declared the “return of inheritocracy,” referring to the rising importance of inherited wealth by younger generations in rich Western countries such as Italy, Germany, France, and the UK. The article drew upon the latest research by economists who specialize in wealth inequality, including Stone Center Senior Scholar and GC Wealth Project Director Salvatore Morelli.

In this interview, Morelli discusses the surge in inherited wealth, what this means for wealth inequality, and potential solutions for the negative effects of the ongoing Great Wealth Transfer.

Many people wouldn’t look at receiving an inheritance as a bad thing, particularly on a personal level. Looking at the larger picture, what are the negative effects of inherited wealth on inequality, economic growth, and mobility?

Morelli: There is nothing intrinsically wrong with inheriting multimillion-dollar fortunes, but such a legacy typically does not come from any particular individual merit or effort. Hence, a society where parental wealth becomes more and more crucial in determining the lifetime chances of individuals distances itself from a “meritocratic approximation” and slowly becomes trapped in what the French economist Thomas Piketty called a “patrimonial capitalism” structure, or what The Economist called a “inheritocracy.”

Wealth transfers in the form of inheritances and gifts, along with individual savings and both monetary and price returns on investment securities and real estate, constitute one of the main mechanisms of wealth accumulation. The resulting inequality of wealth can also lead to greater disparities of opportunities: by transferring wealth from generation to generation, the greater opportunities it grants (for example, as a financial cushion to rely on, or as a means to invest in education, own a home, or set up a business) are also passed on.

The crystallization of wealth positions from generation to generation through wealth transfers could thus have major repercussions for both equity and efficiency. On the one hand, it is unfair for the presence or absence of substantial wealth in the family of origin to overwhelmingly condition the chances of success in life. On the other, a well-functioning market capitalist’s economy should attempt to allocate productive capital into the hands of those most able to “use” it. Dynastic capital transfer does not necessarily appear to be the best allocation choice for ensuring sustained economic dynamism and productivity. Taxation of intergenerational wealth transfers thus appears broadly justifiable in several respects, especially with a generous exemption threshold (the value of assets that can be passed on without incurring any taxation, thus also ensuring “providing” for one’s family members). More progressive forms of taxation (demanding a proportionately higher payment from those who receive more inherited wealth) are generally justifiable to reduce inequality of opportunity and inequality of wealth in the long run.

As The Economist article says: “Wealth transfers — such as inheritances and gifts — have become a growing share of national income in many wealthy countries. Piketty (2011) documented that in France, their share tripled from 5% in 1950 to 15% in 2010. Similar trends were found by Atkinson (2018) in the U.K., and by Acciari, Alvaredo and Morelli (2024) in Italy. Since the mid-1990s, inheritances in Italy have doubled in significance, now totaling about 250 billion euros annually, or 15% of national income. However, despite this rise, inheritance taxes have declined over time, now contributing less than 0.5% of total bequest value.” What factors are driving these trends?

Morelli: Such trends of rising importance in the wealth coming from the past and the declining effectiveness of the taxation on these wealth transfers are becoming a shared features across many countries in the world, as recently documented in preliminary joint work that I have with my colleague Demetrio Guzzardi at the University of Calabria in the south of Italy. The trends are particularly pronounced for the EU-27 group of countries (despite notable heterogeneity across countries) and increasingly true for the U.S.

This is in part the phenomenon that is referred to as The Great Wealth Transfer (GWT) in the press. This GWT refers to the massive shift of assets from older generations — primarily the Silent Generation and Baby Boomers — to their Generation X, Millennial, and Generation Z heirs over the coming decades. While much of the research has focused on wealth transfers in individual countries, our preliminary global estimates suggest that at least $70 trillion will be passed down worldwide. This is likely a very conservative estimate, as this does not account for the likelihood that intergenerational transfers will continue to grow in scale and significance across economies.

If intergenerational transfers continue to rise, as you say, what are the likely implications? And what can be done?

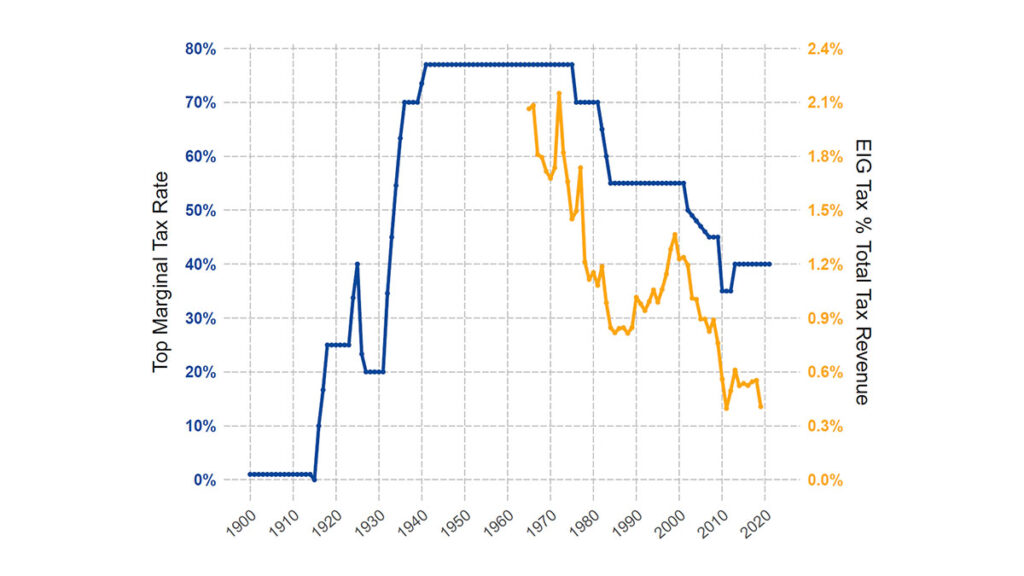

Morelli: In many countries, the relevance of both inherited assets and wealth and also their concentration in the hands of a few has increased considerably. Oxfam’s new report published in January 2025 makes this clear, suggesting that billionaire wealth grew by $2 trillion in 2024 alone, a rate three times faster than the year before. The report also highlights that around 36 percent of billionaire wealth is now inherited around the world. It should also be reiterated that in the face of these trends, however, the effectiveness of wealth transfer tax levies has often decreased in many countries. As shown from our GC Wealth Project data, the top marginal estate tax rate in the U.S. dropped dramatically over the past decades and the relevance of estate tax revenue moved with it.

In my country, Italy, gift and inheritance taxes were even abolished between 2001 and 2006! Now inheritance bequests exceeding 10 million generate taxes paid that are worth only 1 percent of the entire value of the bequest. This tax burden was 6 times higher in the 1990s. The overall inheritance tax revenue in Italy is less than 1 billion euros whereas in France it amounts to more than 15 billion euros. This is emblematic as France’s total wealth and total annual wealth transfers are very similar to the Italian ones. Hence, things can be done differently: the inheritance tax can be strengthened, preserving a progressive structure to reduce long-run equilibrium of wealth inequality and to release important revenues that can be invested back in society.

How? A very interesting proposal was advanced in 2015 by the late UK scholar Tony Atkinson, among others, to implement a so-called “universal inheritance” scheme. This can take the form of an unconditional transfer of an endowment to every person turning adult in a country: say, everyone turning 18 years old. The goal would be a society in which the “birth lottery” matters less and less. Although no measure can completely undo the birth advantage, this disparity can be reduced to make family wealth less of a determinant and decrease inequality of opportunity.

In Italy, the Forum on Inequality and Diversity proposed to transfer a sum of 15,000 euros (approximately 10 percent of wealth per capita) to be paid universally to each person who reaches the age of 18. The Forum also administered nearly 2,000 questionnaires in secondary schools and university classes to assess the degree to which individuals liked the proposed measure. When the monetary transfer and inheritance tax reform are presented together, more than 70 percent of respondents rate positively the idea of receiving 15,000 euros upon turning 18 years old, along with a substantial tax reform.

Interestingly, this proposal is also gaining ground in other European countries. In addition to the UK, similar versions have been advanced in Germany and Spain. In the U.S., the city of Washington and states including Connecticut, California, and New Jersey have already adopted a similar measure, called baby bonds. These are universal trust accounts opened at birth and financed with public funds. Upon reaching the age of 18, beneficiaries can use the funds for wealth-building activities, such as buying a home, investing in education, or starting a business.

Read More: