September 6, 2023

Stone Center Affiliated Scholar Arthur Kennickell worked for more than three decades at the Federal Reserve Board, where he is best known for developing and leading the Survey of Consumer Finances. This is the first in a series of three blog posts by Kennickell, which together give a broad overview of the measurement of personal wealth, largely through household-level surveys, and the use of such data to gauge inequality.

This first post addresses key questions about the definition of wealth. (The second and third posts will focus on wealth inequality and questions related to wealth measurement.) The series was written for the recent launch of the GC Wealth Project website, aimed at expanding and consolidating access to the most up-to-date research and data on wealth, wealth inequalities, and wealth transfers and related tax policies, across countries and over time.

By Arthur B. Kennickell

The GC Wealth Project provides an impressive amount of useful information on the holdings, distribution, composition and, to some extent, origin, of wealth, and it does so for a variety of countries. The website has been carefully curated to support researchers and other interested people in understanding aspects of wealth more clearly and deeply. It also deals carefully with the provenance of the data. This note may help users of the website to understand the information there in a broader technical context and to frame their assessment of the measures reported and comparisons of measures across time and countries.

For a variety of reasons, wealth and its distribution can be slippery to capture. Two are most immediately important. First, while many people act as if the definition of wealth is perfectly clear, there is a great deal of subtlety of definition and valuation that can make a substantial difference in the interpretation of the data. Second, the characteristics of the source of data can make a large difference in the sorts of analyses that can be sustained by the data. For example, in a relatively small number of countries, there are high-quality register microdata on components of people’s wealth, though even such data may contain errors or approximations of the desired information. In other cases, wealth measurement is necessarily more indirect, typically through surveys or sometimes estate data, and any analytical inferences are conditional on the design and execution of those sources, which can vary substantially in ways that have important implications for how the data should be used or interpreted.

This overview develops a framework for what we might mean by “wealth,” the concept of inequality, and the means by which we might measure it. This note does not attempt to cover or reference the very large associated technical literature. The point here is to raise a set of key questions and to provide intuition about their possible answers.

What is wealth?

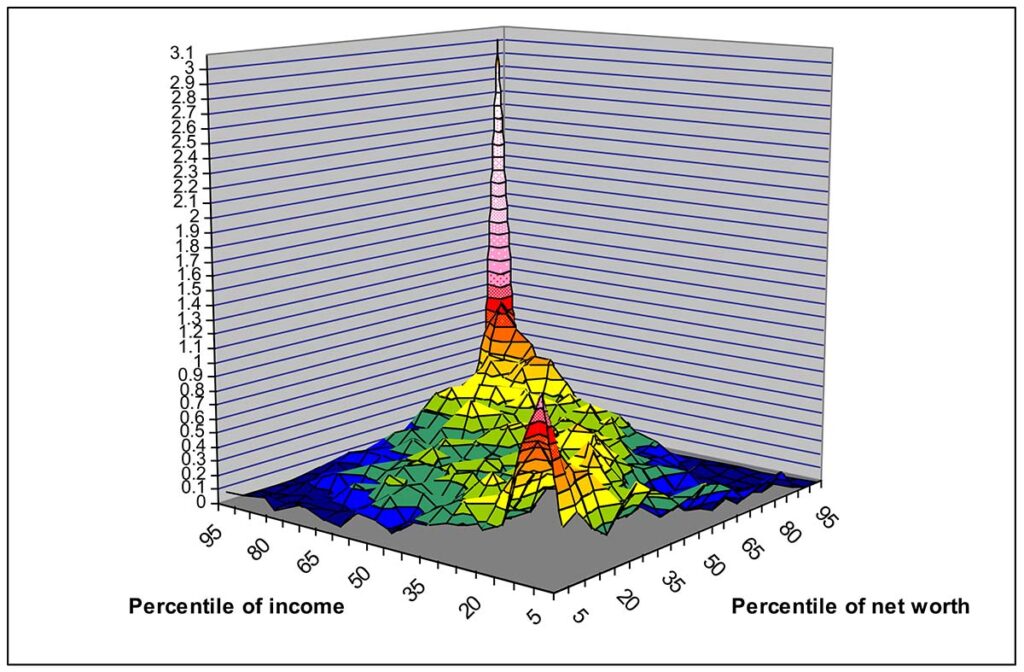

Income and net worth, under the heading of “wealthy” or “the wealthy,” are often conflated in discussions of inequality. But focus on one or the other can yield very different conclusions. Economists tend to distinguish the concepts as “flows” versus “stocks.” Income is seen as a “flow,” with items such as wages, interest or dividends being seen as returns on human, physical or financial capital in a given time period, which then feed into decisions about spending or saving. Across the population, income has non-negligible variability from year to year. Net worth, the concept of wealth principally addressed in this note, is a “stock” measure. That is, it is a sort of inventory at a given point in time, defined as the value of some array of assets minus some array of liabilities. Typically, this wealth measure evolves relatively slowly over time, though it may have a longer-term profile determined, for example, by life cycle patterns of saving and spending; in percentage terms, it may vary more for the very poor and for those who hold wealth in relatively risky forms. In this note, the term “wealth” will be used exclusively to refer to a measure of net worth. To illustrate the differences between income and wealth at a high level, Exhibit 1 shows a copula distribution of measures of income and wealth taken from the 2007 US Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF). Although there is relatively greater coherence of income and wealth ranks at the bottom and the top of their distributions, there remain substantial differences there and especially so across the rest of the distributions.

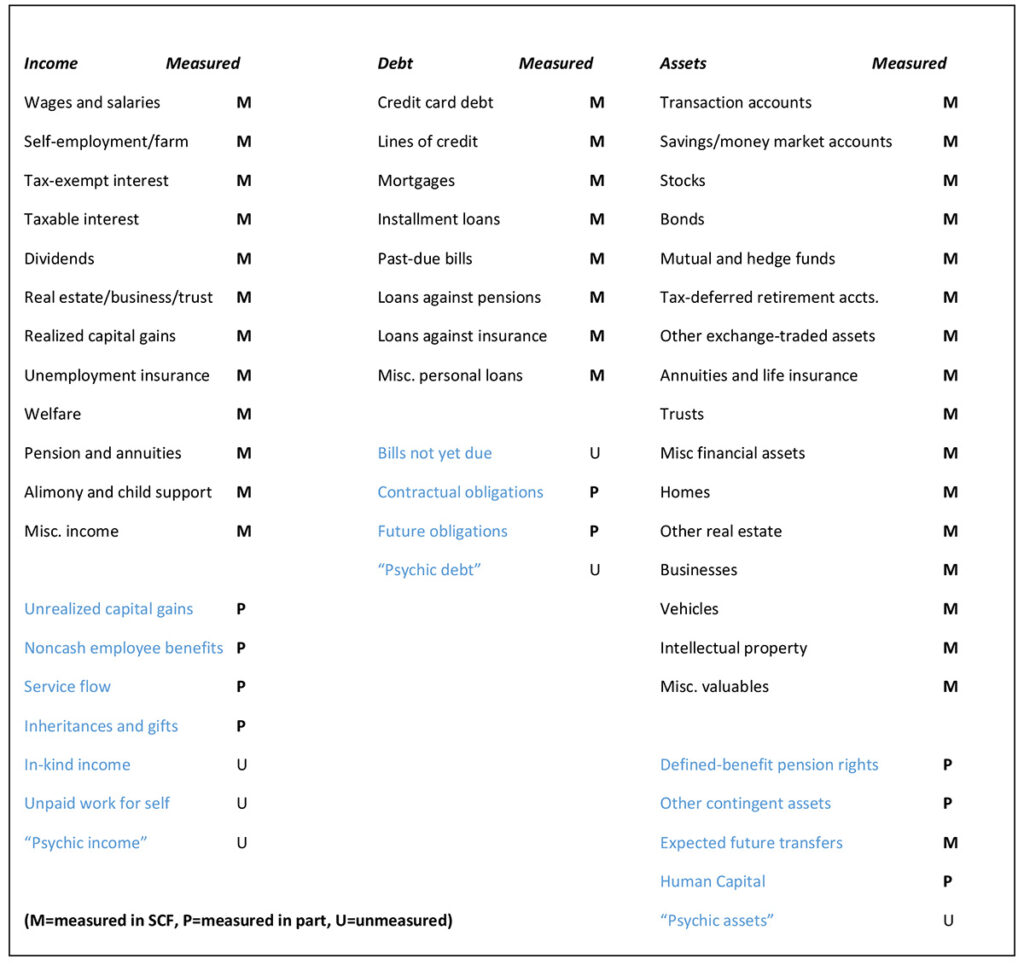

At higher magnification, there may be fuzzy edges to the understanding of income and wealth, such as whether to treat balances in tax-deferred retirement plans as deferred income or as wealth. Exhibit 2 gives a breakdown of wealth using categories commonly applied in the SCF, with a breakdown of income given for reference. Most of the categories seem straightforward — such as savings account or credit card balances. Typically, researchers include as wealth those items over which a person has the power to liquidate or otherwise control the item. In the examples given in this note using SCF data, the wealth measure used is given by the assets shown in black in the exhibit net of the debts shown in black.

Some of the measures not included in the wealth measure (shown in blue in the exhibit) are more debatable. Defined benefit pensions are a particularly difficult item to consider as a quantity of wealth, though it is obvious that anyone who has such entitlements possesses something of value. Valuation of such benefits for someone who is not yet retired would require many assumptions: future stability of and participation in the pension plan, the path of future wages, the survival of the beneficiary or beneficiaries at future dates, the treatment of inflation, and all the detailed conditions that often are part of a pension plan description. Including a wealth measure of Social Security benefits is potentially even more complicated, given that the ultimate benefit depends on the entire history of wages that count toward benefits. A key obstacle is the choice of the time at which to value pensions or Social Security. For young workers, valuing plans only in light of current accrued benefits, as would fit most logically with the treatment of other wealth items, may be seen as disregarding an important entitlement and insurance aspect of such plans. But including (and discounting to the present) the value of benefits as of retirement can be seen as assuming too much certainty about the future and introducing an inconsistency in the treatment of different types of wealth. It is certainly possible to make such assumptions, and some researchers have done so to gain some understanding of the effects of including these items, but the measures do not have the solidity of items that have a current and objectively defined market value, an area where some items included also have problems, as discussed further below. Other items, such as income-only rights to a trust or annuity raise similar issues.

Exhibit 1: Copula distribution of income and wealth, 2007 US Survey of Consumer Finances

Note: The exhibit is a plot of the percentile of income distribution against the percentile of the wealth distribution for the households in the survey, thus the volume under the surface sums to 100. See the text for the definition of wealth used.

There are a variety of other reasons an item may be questionable. First, there are items that may affect behavior as if the items were officially part of the household balance sheet, but do not have that definite status. For example, under “psychic debt” a household might behave as if it had a definite obligation to pay for care of an aged parent or for college loans taken out previously by a child no longer in the household. Second, there are contingent items. For example, a household may serve as a guarantor of a loan by someone else, being liable to repay the loan in the event the person defaults. Third, for some households “social wealth” may play an important role in their financial life. For example, some economic theory suggests that households respond to increases in the national debt by trying to increase their own saving in order to pay taxes for repayment of the debt; many questions would need to be answered for a measure of such debt to be included in the household balance sheet. Similarly, social insurance and such amenities as national parks or clean air are quite important, but also raise questions about how to attribute them at the household level. Similar arguments could be made for other assets and liabilities not included in the measure described above.

How should wealth be valued?

While some assets held in traditional interest-bearing accounts and assets traded in highly liquid markets, such as publicly traded stocks, have a value definable with little ambiguity, the same is not true for many other assets. Closely held businesses, a key asset particularly of wealthy households, are especially problematic. Unless the business is one where there are many comparable businesses that change hands often, survey measures of value depend on the judgment of the owner, which may be affected by such psychological factors as narcissism or shyness. In some cases, it may be difficult to distinguish the value of a business from the human capital of its owner.

Although housing is often taken to have a fairly well-defined value, given the amount of information available online about properties, there may well remain important deviations. For a group of newly constructed homes, there is a (generally) unambiguous sales price. But the older a home becomes, the more its value may depend on factors more difficult to observe for purposes of objective valuation, such as the extent and quality of improvements and maintenance. Typically, a mortgage associated with a property is treated as having a specific outstanding balance at a given time, which is then included in the debts that net against assets to determine wealth. For a mortgage with a freely floating interest rate, this may be a very reasonable treatment. But for mortgages with a fixed rate, treating the balance in this way breaks the comparability with traded corporate bonds with a fixed rate of return; such bonds are repriced in the marketplace as corresponding market interest rates move above or below the return on the bond. With the possibility of refinancing, households could capture some of the gains from lower rates, but it seems rather unlikely households would similarly willingly realize what amounts in this sense to their paper losses from opposite rate movements. This limitation together with the ingrained conventions for analysis argue for treating the mortgage debt simply as the outstanding amount. This discussion serves as a representative of many other such potential critiques of individual wealth measures that may be relevant, depending on the analytical perspective.

Many assets, for example real estate and corporate stocks, may accumulate capital gains without taxations until the gains are realized when the assets are sold. In some cases, if the assets are held until their owner dies and then dispersed to heirs, the gains may escape taxation altogether. Even when assets are subject to inheritance taxes, there are many techniques to minimize values for taxation. Trusts may be structured to escape inheritance or other taxation to pass wealth between generations. Tax-deferred retirement accounts in the US have a requirement that a given minimum proportion of the asset be withdrawn each year after the owner reaches a certain age, and any remainder is taxed as income at the death of the owner or the owner’s spouse. Withdrawals from these accounts are a mixture of deferred income and capital gains. Obviously, ownership and treatment of all these types of assets vary greatly across the population. While it is clear that taking account of ultimate taxation could alter the net sale value of such assets, it would require many assumptions to quantify the effects on estimates such as wealth concentration. This remains an interesting subject for research.

Exhibit 2: Elements of income and wealth, as captured in the US Survey of Consumer Finances

An additional issue, which is relevant both to the analysis of any wealth measure that is dependent on multiple time periods (such as pension valuation) as well as comparisons of values across time, is whether wealth items should be treated as nominal value or should be adjusted to for changes in the price level over time. Adjustment is generally taken as the conventional approach for comparisons across time, though there are sometimes differing views about the appropriate price index to use for the adjustment. Whether adjustment is also relevant for the other purposes depends on the details of the analytical objective.

Whose wealth?

Household wealth surveys typically collect ownership information at the level of the household, except in instances, such as pension accounts, where the item is specifically tied to an individual or there is an important analytical need. But even where there is a specific accounting definition of the personal ownership for an item, various definitions of “marital property” may complicate the practical understanding of ownership within married couples. Moreover, experience suggests that there is sometimes not agreement among household members about who has ultimate claim on an item, suggesting there could be important measurement error to be considered if wealth data are collected at the personal level in a survey. Where there is a need to use survey data to examine wealth at the individual level, a variety of assumptions and careful attention to potential data errors are needed.

In the case of household income, there is often a desire to “standardize” the observed household income to account for differences in household composition. For example, sometimes researchers derive such a standardized measure of income by dividing the total income by the square root of the number of household members or some other weighting of the household members. Because the amount of income saved is typically a small fraction for most households, this method amounts approximately to a rule for allocating the spending of the income, which in a given period might be thought of as affecting household members directly or indirectly.

Thinking about how this approximation alters when saving is a more substantial fraction of income opens a window for understanding how a similar approach might work for standardizing household wealth. Saving may have a wide variety of purposes, some focused on relatively short-term deferral (for example, “saving up” for a vacation or durables) and some on longer-term purposes (for example, retirement or college education for children). If saving is substantial and the purpose is preparing for retirement, it is no longer obvious that, for example, implicitly attributing some fraction of that part of income to children currently in the household has as strong a rationale. Borrowing (“negative saving”) instead of using accumulated savings further complicates the picture, among other things by adding resources to the current period that are implicitly a transfer to the present of income in a different period. Wealth, as the cumulation of all prior decisions about saving or borrowing thereby mixes all the associated motives. Largely because of this general lack of clarity, it appears to be unusual for analysts to standardize wealth for household composition. Nonetheless, for some purposes the ambiguity involved may be acceptable.

A related question is how household data should be “indexed” in analysis. For example, if one desired to show wealth by age, some method is required to select or compute an appropriate age in light of the composition of the household, which may include people with a variety of relationships and ages. Historically, the concept of a “head of the household” may have been reasonably well defined and sufficiently consistent across households that this person’s characteristics could serve as a “reference person” to index the household. Deeper recognition of intrahousehold relationships and cultural awareness of the implications of such assumptions have driven further thought in this area. For example, analysis of a survey might choose the most knowledgeable person, the person with the highest income, the oldest person, etc. In some cases, such as the choice of the person who makes most financial decisions, the potential reference person may not be unique. But whatever approach a survey may take for purposes of efficient survey administration, it is up to the analyst of the resulting data to determine and clearly report the appropriate reference person for the research, keeping in mind that any such approach is usually an approximation in multi-person households.

Finally, connections across households undoubtedly have behavioral effects that are important for understanding wealth. The brief discussion above about “psychic debt” is just a small pointer into the potential complexity of this issue. To varying degrees the social structure in which a household exists may have substantial insurance aspects that could give the household access to private resources or oblige them to give access to their resources to others. In addition, for some households bequests/inheritances may have large effects even before they are given/received, even if the amount and the timing are uncertain, as they usually are. Thus, it is often important in analyzing data to consider whether such “shadow wealth” from inter-household connections is relevant and to use whatever relevant controls are available in the data.

The next post in this series will focus on what we mean by “wealth inequality.”

Read More by Arthur B. Kennickell:

- Stone Center Working Paper Series. no. 37: Chasing the Tail: A Generalized Pareto Distribution Approach to Estimating Wealth Inequality

- Blog Post: What Do the Recent Survey of Consumer Finances Data Show about the Recovery from the 2008 Crisis?